Contributors:

- Mikayla Arnold, SN, UVU - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Assistant Professor - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

- Melissa Christensen , SN, UVU - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

- Zachary Harmon , RN, UVU - Idaho

- Camille Hatch , SN, UVU - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

- Morghan Reid , RN - Utah

Reviewers:

- .

Culture

The Shoshone Indians are a Native American tribe of about 8,000 people. They are direct descendants of an ancient and widespread people who called themselves Newe (nu-wee), which means The People. The Shoshone were separated into three main groups including the Northern, Western and Eastern. These three groups occupied parts of California, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming and Idaho. The largest of these groups settled in the Snake River Valley in Idaho, sometimes being referred to as the “Snake Indians”. Today, there are several places in Idaho named after the Shoshone Indians including Shoshone Falls, the Portneuf (Port-noof) River and the city of Pocatello; the latter two named after Shoshone chiefs.

The Shoshone people were hunter-gatherers and relied heavily on the wildlife, such as buffalo, deer, and elk, to maintain their food supply throughout the winter. While many Indian tribes are well known for jewelry, the Shoshone tribe excelled instead in basket making, becoming well known for their beautiful hand-woven baskets. While their clothing depended greatly on the seasons and the adjustments they had to make due to harsh weather climates, their summer wear was simple with loincloths for the men and aprons for the women.

Among the Shoshone tribes were several famous chiefs. The most well known Shoshone is Sacagawea. Sacagawea was an Indian woman who led explorers Lewis and Clark across the west and to the Pacific Coast in 1805. Although this interaction was peaceful, the tribe would later have several conflicts with settlers. While the settlers were expanding and developing new areas, the Shoshone Indians were being compacted and restricted. During the Civil War, the Shoshone Indians raided the Pony Express routes and wagon trains. In 1863, during the Battle of Bear River, the tribe was defeated. This led to the Snake War, where the Shoshone were again defeated and their resistance to the settlers crushed. In 1875, Ulysses S. Grant ordered a one hundred square mile reservation in Lemhi Valley for the Shoshone Indians. In 1905, however, they were forced to leave their homeland and began their Trail of Tears, which ended at the Fort Hall Indian Reservation.

Norms and Values

Family is an important part of the Shoshone values. They not only live with their immediate family but with their extended families as well, including aunts, uncles, and grandparents. The Shoshone parents and grandparents share the ancestry and history of their people through stories told to their children. They would tell them the stories about the origins of their people and the great stories of the heroes in their tribes past. Because the Shoshone people had no written records, these stories were important to the history of their people (Shoshone Tribe, 2015).

The Shoshone people traveled according to the seasons and followed the animals and food supply. They were often referred to as the “valley people” because they camped in valleys. They were not wasteful and used everything they were able to its full use. Animals were used for food and clothing and every part of the animal was used. They never killed anything they did not intend on fully using (The Northwest Shoshone, 2015).

The Shoshone were a peaceful people, trading with mountain men and fur trappers, but they adopted a war-like attitude following a series of events that happened to them. First, the United States government signed a treaty with Shoshone people for peace, but the United States government did not keep the treaty. Second, the Mormon people also began moving in on their territory. This caused the Shoshone people to fight for their freedom and their lands. This is what started the Bear River Massacre, Battle of Rosebud and Bannock War. Each one of these conflicts and wars had the same turnout for the Shoshone people, defeat (The Northwest Shoshone, 2015).

The Shoshone people now live on several reservations throughout the states of Idaho, Nevada, Utah and Wyoming. They have grown to a group of nearly 30,000. They are waiting to be formally recognized by the U.S. government (Shoshone, 2015).

Traditions, Beliefs, and Attitudes

There are three main traditions of the Shoshone Indians; the Vision Quest, the Power of the Shaman, and the Sun Dance. There is a great deal of focus put into the supernatural world. The Shoshone Indians believe that supernatural powers are acquired through vision quests and dreams. “There were two types of dream powers, one involving a spirit helper, an animal or bird or natural object: another power acquired in dreams carried the ability to be expert in other conventional roles such as hunter, gatherer, warrior, etc.” (ERN, 2005).

The Vision Quest is a ritual for the men of the tribe. If a man in the tribe has not had a vision or a dream, which the elders see as supernatural, they are then prepared to go on their vision quest. The premise behind the quest is that a spirit, typically in the form of an animal, will come to the tribe member and bestow its powers on him and become that man's guardian. During the quest, the youth or adult man is left in a lonely place to fast and pray. The powers bestowed on each man are characteristics of the animal in which the spirit took its form. For example, a turtle gives one the ability to cure the sick because a doctor needs to “see through the patient” in order to diagnose and treat the illness, which is similar to the turtle because it can see through water. Having a beaver as a spirit guide would help that man to be a strong swimmer and having a deer as a spirit guide would correlate with a quick runner.

The Shaman is someone who holds supernatural powers to cure other members of the tribe and also hosts tribal ceremonies (*see health care considerations). There are three types of Shamans in the Shoshone culture, “specialists who cure specific ailments; individuals whose powers only benefit themselves; and those with general curing ability” (Encyclopedia of Religion and Nature [ERN], 2005).

The Sun Dance is a ceremony practiced once a year during the summer solstice and takes place over the course of several days. During the ceremony, a local space is made sacred and serves as a place for the tribe members to renew their relationship with the land and the beings of the world. Tribe members will dance, sing, drum, and some will experience visions, which is important because the ceremony is guided by visions.

Religion

The religious beliefs of the Shoshone tribes stemmed from supernatural powers that often took the shape of animals and other mythical creatures. With variations from tribe to tribe, some of the most popular characters in these stories were Coyote, their mischievous and trickster father of the people; Wolf, Coyote’s brother and wise and revered hero, the creator of the earth; and a people called Nimerigar (Nim-air-ee-gar), a magical race of violent little people that the Shoshone often battled against in their myths. Among other figures that usually took the shape of animals, these are the deities that the Shoshone people believed in and it shaped their culture very much (Redish & Lewis, 2009).

Shoshones based their religion off of visions and dreams that were received from the spirit world. Some of these dreams were sought after as quests where a specific animal spirit would bestow powers to the individual, usually adolescent males, and they would receive guidance. They would go to great lengths to receive these visions, going so far as to fast for multiple days and nights without food, water, or fire, and sometimes cutting off parts of their bodies as sacrifice or creating puncture wounds in their chests to drag buffalo heads on a hook, which would often rip out and tear the wounds open further (Loendorf, 2011).

The Shaman (Sha-man), or medicine men, were a large part of the Shoshone religious culture. They were the practitioners of the religion. They were called on to heal the sick, bless the hunt, perform rituals for ceremonies, and to aid in supplication for spirit quests and to alleviate spiritual problems within the community (“Western Shoshone”, 2015). More information about Shaman can be found under health care considerations.

Another large part of the religious practice of the Shoshone was the ceremonial spirit dances. The most central one was the Sun Dance. The Sun Dance was used as supplication to supernatural powers to ensure blessings and good welfare for the participants as well as the whole tribe and the land itself. It usually took place over several days and nights in the summer where men would dance with increasing intensity while sacrificing food and water. Other dances would take place throughout the year for specific events such as the return of the salmon and to bless the hunt (Eastern Shoshone, 2015).

Today, the Shoshone tribes are split between many different religions, but these practices are still carried out in various reservations and celebrations. Other religious practices of the Shoshone include the Native American Church, adopted from the Plains Indians, as well as over half the tribe populations belonging to Christian sects such as Baptist, Roman Catholic, Latter Day Saint, and Episcopal religions (Eastern Shoshone, 2015).

Sense of Self and Space

The Shoshone people were greatly connected to their land. They respect the native plants and animals and appreciate the land in which they live on. They believe that every plant and animal as well as the land itself has a living spirit and that the plants, animals and people maintain a relationship. Some features of the land, such as caves or springs, have an inherent sacred meaning respected by the tribe. Other places, such as burial grounds, rock art and ceremonial grounds are given sacred meaning through rituals performed there.

The Shoshone tribes believed not that they owned the land, but that they were one with the land in which they inhabited. They have such a strong relationship with their land that any damage done to the land they inhabit is seen as a direct assault on them. It was this principle that caused much tribulation between the tribe and new settlers. As new settlers cut down trees and built homes and communities upon the land, it caused a great disturbance for the Shoshone people. The physical and emotional wellness of the tribe and its culture depends greatly on the preservation of the land.

They are connected so much with the earth and life around them that much of their sense of self is derived from this connection. They connect humans, animals and plants, the physical with the spiritual, and the living with the non-living to create a holistic sense of self. This purpose became difficult for the Shoshone tribes as American settlers moving westward pushed them from their land. Physical separation from their land causes the Shoshone Indians to be disoriented and have a decreased sense of purpose. As they lost their land, they lost their connection to the land in addition to much of their sense of self and purpose. Without land of their own, maintaining their sense of self became very difficult for the Shoshone Indians.

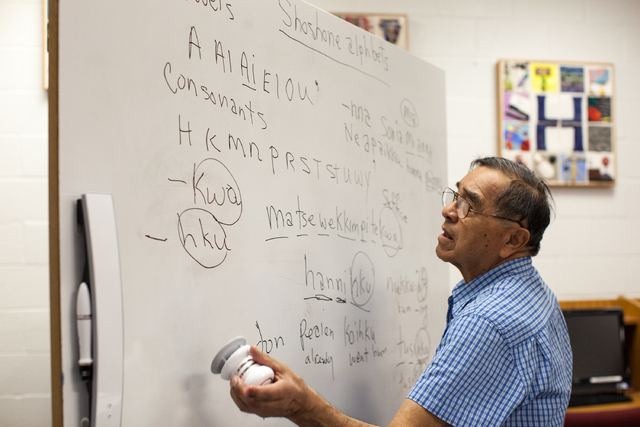

Communication and language

Shoshoni (Sho-sho-nee) is the language spoken by the Shoshone tribes. It is a complex language that is a part of the Uto-Aztecan language family, which includes over thirty different languages. There are four main dialects spoken: Western Shoshoni, spoken by the Shoshone Indians in Nevada, Gosiute (Gos-i-yoot), spoken by the Shoshone Indians in western Utah, Northern Shoshoni, spoken by the Shoshone Indians in southern Idaho and Northern Utah, and Eastern Shoshoni, spoken by the Shoshone Indians in Wyoming. The dialects are similar enough that speakers of one dialect are typically able to understand another dialect.

There are two main spelling systems for Shoshoni. The older system, developed in the 1970s, called the Crum-Miller system is more phonemically based whereas the newer system developed by Idaho State University is more phonetically based. Both spelling systems have their own dictionary and even their own bible.

Over the last few decades the number of people who speak Shoshoni has been slowly dwindling. Today there are only a few hundred people who speak the language fluently and most of them are over the age of fifty. Because there are not many speakers of the language, there has been a recent push to teach Shoshoni to the Shoshone Indian youth. On the Wind River Indian Reservation in Wyoming educators are working to document the large vocabulary and teach the children. Some children are even being taught Shoshoni as their primary language. In addition to this effort, Idaho State University offers classes of different levels to teach the language as part of their Shoshoni Language Project. The university also offers audio online to help with the classes. There is another program held at the University of Utah called Shoshone/Goshute Youth Language Apprenticeship Program. As a part of this program Shoshone youth serve as interns that listen to recordings and read documents and turn them into digital audio files. These files are then made available to other tribe members. This program was responsible for the release of the first ever Shoshone language video game that was released in late 2013.

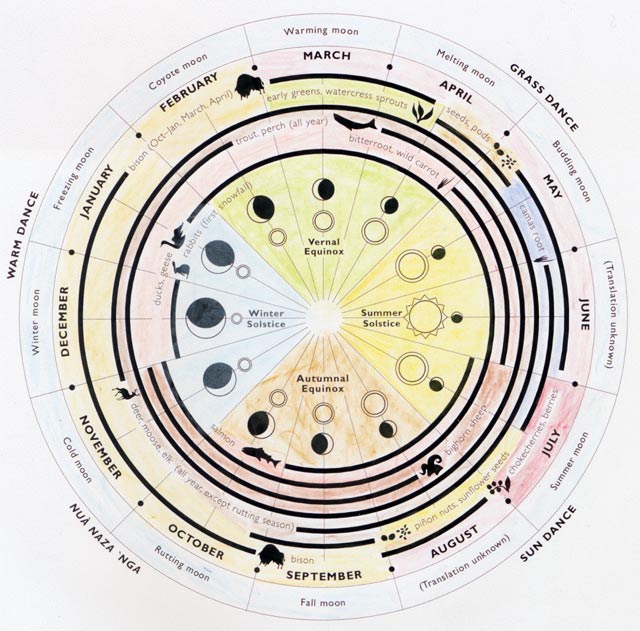

Time Consciousness

Time for the Shoshone people was different than how most people perceive it today. While we are accustomed to twelve months in our calendar year with January set as the New Year, most Native Americans including the Shoshone based the passage of time upon the changes of the sun, the moon, and the seasons. For instance, the passage of years was recognized as “winters”, and the separation between nights and days was known as “sleeps” (Allen & Moulton, 2001).

The lunar cycles were incredibly important to the Shoshone Indians. Each new full moon was a sign of a new time period. They named each of the full moons to help keep track of the passing year. Each name given was associated with that time period up until the next full moon occurred (www.wwu.edu/skywise/indianmoons.html). The following is a chart of moon names and meanings most closely associated with Shoshone calendar months:

|

Month |

Name of Moon |

Meaning |

|

January February March April May June July August September October November December |

goa-mea' isha-mea' yu'a-mea' badua'-mea' buhisea'-mea' daa'za-mea' daza-mea' guuteyai-mea' yeba-mea' naa-mea' ezhe'i-mea' dommo-mea' |

freezing coyote warming melting budding summer starting summer hot fall rutting cold winter |

(http://www.wwu.edu/skywise/indianmoons.html)

The Shoshone have such high regard for the earth and nature; they signify the beginning of the New Year with the spring season. Spring brings an abundance of new life, with the snow and ice melt, and the new growth of plants and the births of animals (Native Net, 2014). Spring was also the time when the Shoshone people began to travel and look for fresh food.

They looked upon the earth not just as a place to live; in fact, they called the earth their mother--it was the provider of their livelihood. The mountains, streams, and plains stood forever, they said, and the seasons walked around annually (Utah History to Go).

Spring, summer, fall, and winter were all significant times. The beginning of each season marked the beginning of a new journey to the next hunting grounds. The Shoshone people were hunters and gatherers, and a nomadic people; therefore, they continually migrated to where the food was. The majority of the traveling was done in the spring and summer seasons in small family units to where the most abundant resources were located to collect enough food for the colder seasons (Native American Indian facts), where they would settle at their winter camp.

Shoshone Indians held dances for each season. The dances were prayers for their people, the plants, and the animals to protect them during each new season and to promote health and growth for the next. The Grass Dance was held during springtime, the Sun Dance was held during summer, Nuà Naza ‘Nga (Noo-a Na-za n-ga) for fall, and the Warm Dance was held in the winter season.

This is a representation of the Shoshone year and season:

Seasonal Round of the Northern Shoshone & Bannock

Adapted from image appearing in North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment

By Lois Sherr Dubin & Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

Relationships and Social Organization

The societal organization of the Shoshone did not have any set definition. The tribe would join together in the winter months and then split again once springtime hit. When the full tribe was together, the members followed rules and regulations of the tribe and the chieftain. There was also usually a leader for each hunting group during the hunting seasons to ensure the hunt would be successful. During the hunt the tribes were disbanded and only a few families would stay together (Eastern Shoshone, 1996).

The Shoshone chieftains and other leaders did not inherit any power from whom they were related to. The way they gained power was through success in warfare and from supernatural powers. Thus, the spiritual leaders were revered and most listened to. The chief had considerable achievements in both warfare and spirituality. He gave orders that affected the movements of the tribe and the various hunts throughout the year (Eastern Shoshone, 1996).

Marriage for the Shoshone was almost always arranged. Many times it consisted of an older man presenting himself or sending a gift to the parents of a newborn or young girl to be considered as a future husband. If the parents believed him to be a good provider and good person, they would agree. If not, the parents refused the arrangement. On rare occasions, the mother of a girl and the mother of a potential husband would play bride tug-of-war. They would each pull on the arm of the girl and whoever could pull the girl across a specified line would win the girl. If the mother of the boy won, he and the girl would be married. The marriage was performed by a spiritual leader where the couple would take vows of monogamy and promise to be chaste in thought and action. Strands of hair would be taken from both bride and groom, tied together, and hidden. If the couple wished to divorce at a later date, they had to find the hair first (Parry, 2014).

Children were cherished and taught to be hospitable from a young age. They were expected to help ease family burdens and did all they could to contribute to the family’s way of life. When their chores were done, children were allowed to play and taught to track. As they grew, Shoshone children took on more responsibilities. They looked after their siblings and grandparents; they collected food and firewood; they took care of the animals and ran many errands. They were considered responsible and important members of the family. Age and sex of children did not matter until they were older and able to take on more adult responsibilities within the tribe (Parry, 2014).

The Shoshone did not keep any kind of written record of their people. Instead, they passed on their histories and beliefs through story. Most of this took place during the wintertime. Parents and grandparents took this time to teach the children about important values and social construct the tribe expected. It was expected that the children would understand and memorize these stories and uphold the messages they portrayed (Parry, 2014).

Education and Learning

Education has always been a part of the Shoshone culture. Instruction was at first based on skills that were needed for their lifestyle such as pottery, gardening, harvesting crops, or tanning hides. Parents and grandparents would teach their children these essential skills throughout their lives until they had mastered them. These types of skills are still passed on to Shoshone children but their education has changed to going to school and learning skills that will help them achieve in the society now such as math and writing (Rist,1961).

A study was done on how Shoshone children learn the best. The study was done between public schools based on non-Indian needs and a school specifically for Indian needs. Shoshone children performed much better in the school with specific needs and backgrounds. The children were able to have their needs met such as language difficulties, vocational training and economic adjustment, because of the special attention that the schools specifically put on these subjects. This helps Shoshone children succeed. They also learn about their culture’s history (Rist, 1961). Many schools throughout the Western United States are available for learning specific to the Shoshone culture. They are located mostly on the Shoshone Indian reservations (History of Bannock Shoshone Tribes, 2015).

There are many different scholarships available for individuals in the Shoshone culture to continue onto higher education. These scholarships provide financial aid to students of the Shoshone tribes to help them meet their educational goals, develop leadership and help the needs of the tribe such as accounting, natural resources, healthcare, and engineering. They hope that by providing college education opportunities within their tribe, they can strengthen their tribal program and ensure a healthy, constructive environment for their future generations (Eastern Shoshone Education, 2015).

Food and Feeding Habits

The traditional Shoshone people would gather rice, pine nuts, seeds, berries, nuts, and roots. They would also gather eggs from nests if they could find them. Meat was also a very important item in their diet. They hunted big game animals such as deer, buffalo, elk, moose, and pronghorn (The Northwest Shoshone, 2015). They also hunted small animals such as rabbits, squirrels, ducks, grouse and doves (The Shoshone, 2015). The Shoshone people would use spears and fishing poles to catch fish in the rivers and streams (The Northwest Shoshone, 2015). They used a range of weapons to hunt for these animals such as lances, spears, hatchets and axes (Shoshone Tribe, 2015). They would sundry the meat to use throughout the winter (The Northwest Shoshone, 2015). The members of the Shoshone tribe were not a wasteful people. They would not gather more than was needed and would use all that they gathered. They would not kill for recreation or pleasure. Every part of the animal was used for food, clothing, shelter or other needs (The Northwest Shoshone, 2015).

When settlers began coming into the Shoshone territory, their traditional food sources became scarce. They learned from the settlers and began to farm and irrigate the land in order to grow their own food. They grew pumpkins, squash, corn, wheat, barley and other crops. They also began to take care of their own livestock to later butcher and eat (The Shoshone, 2015).

Many Shoshone use their gardening techniques to grow their fruits and vegetables today. They also continue to raise cattle and other livestock on their reservations. Most Shoshone people shop at the supermarkets and have a normal diet of grains, protein and meat, dairy, and fruits and vegetables (The Shoshone Today, 2015).

Work Habits and Practices

Prior to the Shoshone tribes being forced into reservations, their work was very simple. It consisted of the work required to maintain life for the tribe, such as, hunting, gathering, building shelters, making clothing and basket weaving. Occasionally a member of the tribe would complete work in exchange for money. Each member of the tribe contributed to the well being of the entire tribe.

From 1853 on, the Shoshone tribe worked closely with Mormon settlers in the Utah and Idaho regions. The Shoshone tribe taught the Mormons how to hunt and gather in this new type of land and the Mormons sought to convert the Shoshone tribe to Mormonism. The two groups maintained friendships and worked closely together for several decades planting crops and building shelters.

In 1875, government agencies were displeased with the intense involvement between the Shoshone tribe and the Mormons, military forces were sent and demanded the Shoshone’s return to their reservations and cease contact with the Mormons. Due to this, the Shoshone tribe lost a great amount of their combined crops. The groups were not stopped by the military involvement and continued to replant crops and work together. In 1877, a dam and irrigation system was constructed to supply the two groups crops with the water required (Native American Netroots, 2012).

Once the English settlers had taken over much of the land and the Shoshone tribes were relocated to reservations, their definition of work changed drastically. Ojibwa (2012) explains that following the relocation to reservations in the nineteen thirties, many Shoshone Native Americans worked at trading posts. They made goods to sell to others such as jewelry, weapons, clothing and baskets. Through the trade and sale of their handmade items they were able to provide the tribe with the things they needed to survive. This, however, was still very different from how they had lived prior to reservations.

Healthcare

As a Registered Nurse it is important to first consider the beliefs and values of our patients. This is especially true for Native American patients.

The Shoshone believe that there are two different causes of disorders, those which are caused by the supernatural, and those that are not. The physical trauma and illnesses that were not believed to be caused by the supernatural were treated with many different types of herbal remedies (Western Shoshone, 1996). While, illnesses that were believed to have been caused by supernatural beings were treated with the ceremonies and rituals of Shamans, this often consisted of the sucking out offending objects or blood (Western Shoshone, 1996).

Shaman

The Shoshone shaman as three different jobs, one of which is to help heal the sick. They used hundreds of different herbs and tools to help them in their work. Sweat lodges are used for ceremonies and to help detoxify those they treated (Tribal Directory, 2014). Smudge sticks (or a bungle of dried herbs), which are often burnt, are used to purify and cleanse the spirt, mind, and body (Tribal Directory, 2014) and medicine wheels which are typically used for ceremonial purposes can help also be used to help healing (Tribal Directory, 2014). Occasionally if the Shaman was unable to help their patient they would return their money, or if the Shaman to refuse services they were sometimes executed (Western Shoshone, 1996).

Current Health Considerations

Currently Native Americans, including the Shoshone, are facing increasing health challenges, like diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. This could be attributed to their genetics, a rise in obesity rates, sedentary lifestyles, and the change in their people’s diet (McLaughlin, 2010). Due to the effects of diabetes they have more long-term complications that develop at younger ages, and cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death (McLaughlin, 2010).

The Western Shoshone Native Americans in Nevada also have a higher cancer rates. These increased rates could be the effects of nuclear test nuclear weapons testing that were done upwind from Native American communities (George & Russ, n.d.). The effects of the fallout from these tests have tainted wild game and the vegetation their livestock consume which results in the contamination of their primary food sources (George & Russ, n.d.).

Pictures

- http://www.reviewjournal.com/news/nevada/shoshone-tribal-member-passes-native-language-photos

- https://www.trailtribes.org/lemhi/sites/[email protected]

External Links

References

- Allen, J. L. & Moulton, G. E., (2001) Discovering Lewis & Clark: Indian Spatial Concepts. Retrieved October 19, 2015, from http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/1263

- American Indian Tribes. (2003). Retrieved October 6, 2015 from http://www.planning.utah.gov/usfs/2GAmericanIndianLinkages.pdf

- Eastern Shoshone Education. (2015). Eastern Shoshone Education. Retrieved from http://easternshoshoneeducation.com/13401.html

- Easter Shoshone. (1996). Encyclopedia of World Cultures. The Gale Group, Inc. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3458000076.html

- Eastern Shoshone - Religion and Expressive Culture. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.everyculture.com/North-America/Eastern-Shoshone-Religion-and-Expressive-Culture.html

- George, P. & Russ, A. (n.d.). Nuclear Testing and Native Peoples: Tribal research uncovers unexpected exposures. Retrieved from http://reimaginerpe.org/node/165

- History of the Bannock-Shoshone Tribes. (2015). Shoshone Bannock Tribes. Retrieved from http://www.shoshonebannocktribes.com/shoshone-bannock-history.html

- Loendorf, L. (2011, December 14). Vision Quest Structures. Retrieved from http://www.pryormountains.org/cultural-history/archaeology/vision-quest-structures/

- McLaughlin, S. (2010, October 2). Traditions and Diabetes Prevention: A Healthy Path for Native Americans. Retrieved from http://spectrum.diabetesjournals.org/content/23/4/272.full

- n.a. (1996). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: Western Shoshone. Retrieved from http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1G2-3458000243.html

- n.a.(2014) Tribal Directory: Native American Healing. Retrieved from http://tribaldirectory.com/information/native-american-healing.html

- n.a. (n.d.) American Indian Moons. Retrieved October 12, 2015, from http://www.wwu.edu/skywise/indianmoons.html

- n.a. (n.d.) Native American Indian facts. Retrieved October 12, 2015, from http://native-american-indian-facts.com/Great-Basin-American-Indian-Facts/Shoshone-Tribe-Facts.shtml

- n.a. (n.d.) Trailtribes.org: traditional and contemporary native culture. Retrieved October 19, 2015, from http://trailtribes.org/lemhi/great-circle.htm

- n.a. (n.d.) Utah History to Go. Retrieved October 12, 2015, from http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter2.html

- Native American Netroots. (2012, April 1). Retrieved November 19, 2015, from http://nativeamericannetroots.net/diary/tag/Shoshone

- Parry, M. (2014). The Northwestern Shoshone. State of Utah. Retrieved from http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter2.html

- Redish, L., & Lewis, O. (2009). Native Languages of the Americas: Shoshone Indian Legends, Myths, and Stories. Retrieved from http://www.native-languages.org/shoshone-legends.htm

- Rist, S. Severt. (1961). Shoshone Indian education: A descriptive study based on certain influential factors affecting academic achievement of Shoshone Indian students, Wind River Reservation, Wyoming. Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers. Paper 3549.

- Shoshone Tribe. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2015 from http://www.warpaths2peacepipes.com/indian-tribes/shoshone-tribe.htm

- Shoshone Tribe Facts. (n.d.). Retrieved September 10, 2015, from http://native-american-indian-facts.com/Great-Basin-American-Indian-Facts/Shoshone-Tribe-Facts.shtml

- Shoshone Indians. (n.d.). Retrieved September 10, 2015, from http://www.indians.org/articles/shoshone-indians.html

- Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved September 15, 2015, from http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Shoshone

- Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved September 20, 2015, from http://www.studiesincomparativereligion.com/Public/articles/browse_g.aspx?ID=131

- Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved September 20, 2015, from http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.na.105

- Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved September 20, 2015, from http://plainshumanities.unl.edu/encyclopedia/doc/egp.rel.046

- Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved September 30, 2015, from http://www.omniglot.com/writing/shoshone.htm

- Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved September 30, 2015, from http://www.native-languages.org/shoshone.htm

- Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved October 11, 2015, from http://shoshoniproject.utah.edu/?pageId=5750

- The Shoshone. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2015 from http://ilovehistory.utah.gov/people/first_peoples/tribes/shoshone.html

- The Shoshone Today. (n.d.). Retrieved November 9, 2015 from https://sites.google.com/a/apps.edina.k12.mn.us/emilie-shoshone/the-shoshone-today

- The Northwestern Shoshone. (n.d). Retrieved November 9, 2015 from http://historytogo.utah.gov/people/ethnic_cultures/the_history_of_utahs_american_indians/chapter2.html

- Thoemmes (2005) Encyclopedia of Religion and nature. New York, NY: Bloomsbury Publishing http://www.religionandnature.com/ern/sample/Walker--Shoshone.pdf

- Western Shoshone - Religion and Expressive Culture. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.everyculture.com/North-America/Western-Shoshone-Religion-and-Expressive-Culture.html