French Polynesian Culture

Contributors

- Chad Call, RN - Utah

- Anna Cueva, SN - Utah

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

- Melissa Guest, SN - Utah

- Abby Rawlinson, SN, - Utah

- Courtney Timpton, SN - Utah

Reviewers

- .

Culture

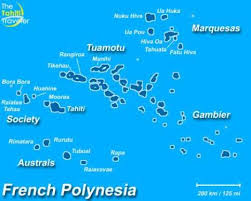

French Polynesia is an extended possession of France located in the Pacific Ocean. It includes 118 islands made up of volcanic rock and coral. These islands are further broken down into five island groups: The Society Islands, the Tuamotu Archipelago, the Gambier Islands, the Marquesas Islands, and the Tubuai Islands. Tahiti, which became a French colony in 1880, is the most populated and belongs to the Society Islands. In 1946 the islands became an overseas territory and in 2004 gained “overseas country” status (24). This gives the different islands autonomy over health, town planning and the environment. France controls the justice, education, security, public order, currency, defense and foreign policy.

Polynesian culture is rich in dancing, music, tattooing, and religion. Many of these elements have disappeared due to the influence of missionaries who arrived in the 18th century and suppressed the traditional culture (37). These French missionaries stopped practices like cannibalism, child sacrifice, nudity, and brought with them diseases that nearly wiped out the indigenous population. However, the French gave them greater economic stability and a written language (19). Pro-independence movements started in the late 1970s and with this came a greater attention to the Polynesian culture. Tahitian became an official language in the late 20th century, although French is still the official language of the islands.

Traditional Polynesian culture revolves around a philosophy known as “aita pea pea” (eye-tah pay-ah pay-ah), translation is ‘not to worry’. Most Tahitian are not only generous and friendly to each other, but this generosity is extended to all people, it is their way of life.

Norms and Values

French Polynesians identify more with Polynesian culture than French culture although they have a more urbanized way of living than some Polynesian groups because of the French influence (4). There is a certain philosophy among the French Polynesians that values tradition. They keep detailed genealogies, pass down chants, songs and legends in order to preserve their heritage and things they regard as important to their heritage (5).

Tattoos are a large part of the culture in French Polynesia. The word “tatu” (tah-too) in Polynesian languages is where the English word tattoo came from. Captain Cook, a European explorer brought a Tahitian man back with him from one of his voyages, this man named Ma’i had tattoos. Ma’i’s made tattoos become much more popular in Europe (6). Tattoos were a way to deliver information about its owner. Each tattoo had significance and meaning. Tattoos were a way of showing character, position, and hierarchy, it was also a way to show their spiritual power (7).

Dance is another way that the French Polynesian people express themselves and pass down their beliefs to future generations. In the past dancing had a way of being linked to all aspects of life, there were dances to welcome people, to pray, to threaten enemies, and dances to express joy. Each village would have a dance platform in a special location, so all could participate. Many emotions could be expressed through different types of dance (6). Dancing is still prevalent in today’s society but not to the extent that it used to be.

Traditional music accompanies dancing. Traditional instruments used in French Polynesia include: to’ere (toh eh reh) (horizontal slit-gong wooden drums), fa’atete (Fah ah teh teh) (upright wooden drum), pahu (pah hoo) (sharkskin covered percussion instrument), and vivo (vee voh) (bamboo nose flutes) (8).

Family and heritage is of great importance to the Polynesian people. These people are very generous and loving to all that they come in contact with. Family traditions are passed down over the generations through music, dance and other traditions.

Traditions Beliefs and Values

Within the Polynesian Culture and tradition, land is commonly owned and shared by families. Because this communal system of land owning is strictly through families, it is thought to be like communism, but at a family level. For example, if an individual was unable to provide food for themselves, a family member would be expected to share their crops and harvest. This type family system provides others with means to be cared for (9).

Within French Polynesia, foreigners who wish to obtain land titles have issues in getting permission to buy land because of the strong Polynesian beliefs and ties to their ancestors who once owned the land (2). Additionally, ancient Polynesians developed classes in which denoted their position within the society. The three main classes included chiefs and priests, landowners, and commoners. An individual's position in society was strictly hereditary. Whereas an individual’s status and wealth correlated with one’s physical size. Although some aspects of the classes and social status has changed or diminished over time, large physical size is still an unofficial indicator of high social status (9).

It is a common traditional practice within the French Polynesian culture to greet guests with great hospitality, respect and generosity. Specifically, Tahitians greet one another with kind handshakes or welcoming exchanges of cheek kisses. Polynesian’s believe it is rude and impolite to not shake hands of every individual in a room when being greeted, unless the group is overly crowded. Another impolite gesture is to not take off one’s shoes after being welcomed into one's home (14). Traditional Polynesian hospitality includes pampering guest with food, lodging and exchanging of good times. It is also expected of the guest to accept the hospitality by partaking of prepared food and lodging, as well as reciprocate the same hospitality if the roles were to switch (19).

Ancient and modern Polynesian attitudes towards premarital sexual relationships are generally relaxed and leisure driven. All children are accepted and welcomed in the large extended family mindset and culture whether the child was born in or out of wedlock. Most individuals are to some degree a part of the Polynesian extended family; thus relationships are not easily distinctable. It is common for adult women to be referred to “auntie” regardless of their actual family relation (9).

Religion

When missionaries first arrived in Tahiti from Britain, they sought to convert the indigenous population to the Protestant faith. The king at the time, King Pomare, was not recognized throughout all the islands as the rightful ruler. In an attempt to unify the islands, he welcomed the missionaries in exchange for political support. It was then that his son, Pomare II became the first islander to be baptized (26).

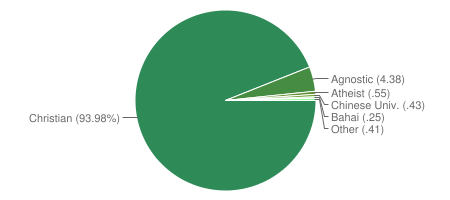

In spite of the British missionaries’ and King Pomare’s efforts to stop other travelers from reaching the islands, all types of missionaries continued to come from many places, preaching many religions. In 1830, French Catholic missionaries arrived and converted people in the Gambier and Marquesan Islands. In 1844, Mormon missionaries arrived and met their first converts in the Tuamotu Islands (26). This strong religious influence is still present today as the predominant religion in French Polynesia remains as Christianity, with a total of 93.98% of the population (9). This includes the Protestant, Catholicism, and Mormon faiths that started, and has grown with Seventh Day Adventist’s, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and others.

The religious influence that King Pomare started to gain power is still present today. For example, French Polynesia does not practice secularity, or the separation of church and state (26). In fact, many government or political meetings are begun with a prayer. The specific type of prayer depends on which religion is the predominant one in that region. Pastors even have an active role outside of their church and exercise influence over political decisions (12).

Prior to these religious changes, the French Polynesian people practiced their own beliefs with multiple gods that lived in a different realm, temples to worship, and ancestral spirits that remain on Earth. Some of these beliefs have continued today, even with the change to Christianity. For example, many ancient Polynesian temples remain standing today and are considered holy places. Many islanders believe the soul is the source of life and may exit the body and wander during dreams. Others believe in the presence of two souls in the body. When dying the true soul will leave the body and go to God when death comes, while the other wander the village (12).

Sense of Self and Space

Most of the people throughout French Polynesia islands may be classed as Polynesian, although there is a part of the population that is of European or Asian descent (37). Respectively European descent and Chinese descent each make up about one-eighth of the population (37). These are the three main ethnicities that make up the islands.

In French Polynesia two major settlement patterns existed before European contact: hamlets and villages (21). Hamlets comprise of a few households, typically four or five and were common on the larger volcanic islands where resources were scattered over a range of different terrains. The benefit of this was that two or three households could share and pool resources together. They often have gardens, taro patches, and coconut and breadfruit trees in the immediate vicinity (21). Villages on the other hand are typically made up of 30 or more houses connected by a network of paths along the coastline (21). On the high volcanic islands, villages are spaced several miles apart and typically include a church, a government house, a school, shops, a pastor’s home, and a few residences (37).

Today in modern day French Polynesia there still exists hamlets and villages in the more rural communities and countryside, but now a large portion of the various islands are now densely populated and reflect the colonial style construction that was influenced with the European migration (13). These are densely developed areas that include a large commercial and government center, as well as military and port facilities (13). According the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) 55.9% of the population live in an urban area (35). They estimate that there is a 0.85% annual rate of change of urbanization of the population that occurs in French Polynesia.

Communication Style and Language

French Polynesia has two official languages: French and Tahitian. 61% of the population speaks French and 31% speaks Tahitian. Other languages spoken throughout the islands are: English, Hakka, an Asian dialect, and a variety of Polynesian languages. A few examples include: Mangareva, Austral, Marquesan North, Marquesan South, Rapa, and Tuamtuam (2). The Polynesian languages are spoken by less than a million people, including but not limited to: Tongan, Samoan, Maori, Micronesia, and Melanesia.

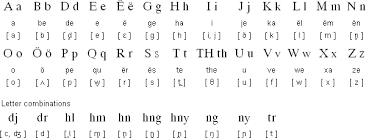

The Polynesian language was not written down until a convicted, but later pardoned mutineer, Peter Heywood, wrote down the Tahitian vocabulary while waiting to stand trial (3). Later on, English missionaries along with the help from the king, translated the bible into Tahitian. These early missionaries decide which Roman letters to use based off which would sound most like the Polynesian language. Then in the 19th century, John Davis, a Welsh historian and linguist proposed on March 8th, 1805, a Tahitian spelling system that used the Latin alphabet (1).

The Tahitian alphabet consists of 13 letters:

the consonants f, h, m, n, p, r, t, and v- the vowels a, e, i, o, and u

Every syllable ends with a vowel and there are no silent letters. Most of the letters are pronounced the same way you would in English, with the exception of r, which is pronounced with a slight click of the tongue at the top of the mouth.

The French Polynesian communication style differs from other cultures. They say hello by a kiss on the cheek, handshake, and they greet everyone in the room. When Polynesians say “la ora” or “la ora na”(yo-rah-nah) this literally means “let there be life” or ” let your life be.” It is their way of saying hello, but it is more than that; they focus on health and a wish for longevity on the people they greet. “Maeva” (mah-yeh-vah) is also a greeting which means prestige or power residing in the viscera. This represents great emotions, sentiments, and sensations; what westerners would call heart (20). When you are welcomed by this word they are welcoming you to their home, the food and above all their heart.

Food and Feeding Habits

Since ancient times weight has played a vital role within the French Polynesian culture. The phrase “fat is beautiful” represents the common mindset Polynesian people have towards physical appearance (7). French Polynesians consider a heavy or large body a sign of physical attractiveness and beauty. During ancient times, celebratory feasts called “fattening rituals” were held to increase one’s sexual attractiveness and lustful nature (7). Throughout the year’s cultural practices have evolved and fattening rituals are no longer performed, and lifestyle and diet changes have been altered. Regardless of the evolutions in diet, obesity is still commonly found among the French Polynesian people and is still strongly embraced within the islands (7).

Among the islands of French Polynesian, food plays a central role within the Polynesian culture. Common traditional Polynesian hospitality involves pampering guests with food. Because food is thought of as gift, it is considered very offensive for guests not to indulge in food that a host prepares and shares. Within the culture food also represents generosity, prosperity, and support (18). Additionally, the sharing of one’s food is a way to express love and friendship. Within the Polynesian culture, pork is the most common meat and is normally roasted underground and served during ceremonial feasts, religious gatherings, and special occasions. Different parts of the pig are given according to one’s social standing (8).

French Polynesian food is popularly known worldwide for its exotic fruits, fresh seafood and French influence. Due to French Polynesia's diverse background of many ethnic groups, the cuisine is also influenced by Italian, Chinese, and Vietnamese cultures (31). Traditional Polynesian diets consist mainly of starchy foods from root vegetables and fruits. Examples of common starchy food include: taro, green bananas, breadfruit, cassava, and yams (27). Most traditional French Polynesian meals consist of “poi” (poi, poh-ee) which is boiled or baked taro. Taro is a starchy vegetable root that is pounded, fermented, and moistened to create poi (32). Along with poi, the meal includes the choice of green bananas, breadfruit, pork or fish. Most Polynesian dishes are cooked and sweetened in coconut milk, and involve a variety of seaweed species, either as a condiment or vegetable option (27). It is common traditional practice to cook traditional dishes inside the “ahima’a” (a, he, ia-mia) an underground oven. In the ahima, hot earthy stones are placed inside to help cook traditional dishes such as: mahi-mahi, tuna, suckling pig, chicken, shrimp, taro, green bananas, and breadfruit (8). The food is first wrapped in banana leaves and later placed in the ahima’a. Once all the items are placed in the oven, more banana leaves will be placed over the food to enhance natural flavors. Lastly, sand or old mats are used to seal in the heat and produce a steam cooking effect.

Time Consciousness

In French Polynesia there are 3 times zones that cover the 118 islands that make up French Polynesia. These time zones include: Tahiti Time Zone UTC-10:00, Marquesas Islands Time Zone UTC-09:30, and Gambier Islands Time Zone UTC-09:00. UTC stands for Coordinated Universal Time. This is the universal time that is used throughout the world. UTC -10:00 means that the times zone subtracts 10 from the universal time (3). For example, if it is 6:00 pm universal time this means it is 8:00 am in UTC -10-time zone. Time zones establish what time it is in a certain location. However, “island time” tends to take over the time established by time zone and clocks.

Island time can be defined as a time vacuum created by the ocean’s presence, it is a carefree slow environment, things will get done when they get done (24). The people on the islands live by the philosophy aita pea pea (eye-tah pay-ah pay-ah) or “not to worry” (15). In French Polynesia, the people ride their bicycles down the street saying “bonjour” to those they pass by, not in a hurry to get to their destination but instead enjoying the ride there (25). Time comes and goes much differently on the islands than in the United States. Time runs on the sun’s schedule or by the rhythm of the sun (26). People are up with the sun early in the morning. It is a simple and peaceful life. The people like to take time for their families by spending time out of their normal work week to rejuvenate and relax with their family to bring a more relaxed atmosphere (27). The relaxed island life is characteristic of the French Polynesian culture. The people are relaxed welcoming and easy going with no pressing deadlines rushing them.

Relationships and Social Organization

There is one main way of social organization in French Polynesia. That is the class structure that closely mimics that of metropolitan France: small upper class, large middle class, large lower-middle class, and a small number of poor people (14). The upper class includes wealthy Polynesian-European families, Chinese merchant families, and foreign residents. The middle class includes members of all ethnic groups. These households typically own their own homes and have at least one source of steady income in the household (14). The Polynesian hierarchy of ranked titles and chieftainship has disappeared. But Polynesians continue to keep detailed genealogical records, and the descendants of chiefly families are aware of their history, as well as some use it for social gain. The descendants of the Tahitian monarchy are socially prominent (14).

Class structure is most evident by the outward display of imported goods such as automobiles and clothing. There is residential segregation of social classes in the urban areas of Tahiti, with oceanfront and ridge tops dominated by the upper classes, the flat littoral plain by middle-class households, and the interior valleys by lower-class households. On the outer islands, house style and size also mark social stratification, while location is less indicative of class (14).

Men typically are the breadwinners and head of families while the ideal roles for women are nurturers and helpmates. However, because men are typically breadwinners does not translate to an ideology of male superiority. Belief is in the interdependence, complementary, and equality of men’s and women’s activates and capabilities (14). They complement each other and work together to function and live. Residents adore children, and most couples look forward to raising a family (14). Infants and children are raised under the influence of parents as well as grandparents, siblings, and other relatives. Infants as well as the elderly are the center of attention in households (14).

Education and Learning

French Polynesia has a 98% literacy rate (13). Even with this impressive percentage, an education in French Polynesian is much more than formal schooling and learning. An education also encompasses socializing and behavior. Initially, children are socialized within and outside of their family unit (13). In the beginning children receive limited guidance to help increase their own autonomy. Many islanders also believe the children will learn how to appropriately interact within their play groups if given the chance (13). They believe children will become more docile and want to behave correctly.

French Polynesia’s formal education system is very similar to that of France. There are primary schools for children ages 5-12 and secondary schools for 13 to 17 year olds (6). School is mandatory until age 16. A free and mandatory education is guaranteed by the French Polynesian government, primarily through public schools. Although some funds are also provided to private schools owned by churches (6).

After secondary school, vocational and tertiary education is available. Vocational training refers to skill and trades, while tertiary is higher education like a university (6). For islanders seeking a higher education, they are eligible to attend a university in France if they wish. However, the University of French Polynesia located in Outumaoro is also an option. This university is a scientific, cultural, and professional education institute that deals with researching. Available for its students are bachelors and graduate degrees in various specialties and studies (6).

Work Habits and Practices

Work practices in French Polynesia are heavily influenced by who their family is. For example, in the government sector, which is the largest supplier of jobs, higher positions normally go to European-Polynesians and Polynesian-Chinese residents (14). The lower positions typically go to Polynesians where women do clerical work and men do public work. Currently, men are the principal job holders in positions like skilled and unskilled labor such as agriculture, construction, fishing, and transportation (14).

There are other areas besides the government sector where French Polynesians have an opportunity to get a job. Commercial Activities include the import business which is dominated by Polynesian-Chinese and European- Polynesians family-owned businesses. Big companies control airline, hotel, construction and energy sections of business. However, people who live there are able to work for these big corporations (12). Other job opportunities include: boat-building, ship-repair, factories that make beer, soft drinks and fruit juice (there are only a few), water purification, importing food, and other goods, exporting local products such as, black pearls, coconut products, fruit, flowers, and handmade goods (12).

Work ethic has changed in the past 150 years in French Polynesia. When the first white missionaries came to the Pacific Nations they noted in their observations, that the Islanders had ‘poor work habits’. They explained it was because instead of working at one job all day, every day, they were used to doing many different jobs. One day might be spent fishing, another day rethatching a house, and another day working on a canoe. They were not used to working steady jobs, and that frustrated the missionaries and traders who concluded that they were lazy because they could not work a steady job. But now as big companies have moved in, and western lifestyle is becoming more normal their work ethic is changing to be able to work steady jobs (5).

Healthcare

Within French Polynesia, the health of it’s people is considered moderately good (11). Some believe, tropical illnesses are of great concern for islanders. While others believe, the lack of proper healthcare plays a larger role in the life expectancy of Polynesian residents. Although, tropical illness exist and while only a limited amount of healthcare is available, the major cause of health problems stems from something else. Most causes of major health problems stem from obesity, hypertension, Type II diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases (17). Due to cultural practices and food habits, islanders are dealing with the health challenges related to obesity rather than tropical illnesses. Considering how the role food plays within the French Polynesian Culture, many individuals tend to have low compliance with modifying lifestyle practices. Additionally, most Islander people have a relaxed mindset towards healthcare, and do not feel the need to visit or follow-up with physicians regarding their health (17). The idea of long-term medicine and lifestyle modification is foreign to many Islander patients, thus the need for better education is a continuing process.

According to the organic law, health is the responsibility of the French Polynesian Government. The health Directorate’s mission is to implement, by any means at its disposal, public health objectives determined by public policies (4). It is in charge of health program monitoring, coordination, implementation, control and evaluation, which contribute to public health objectives (4). Some of these objectives include: develop care channels and networks, maintain and improve equity in access to care by strengthening local-level and, combined curative interventions and prevention by reinforcing prevention activities, health education and promotion (4). The budget for prevention activities like youth sports, transports and, education come from the taxation of sugar and alcohol created in 2001 this roughly comes to $13-$15 million US annually.

French Polynesian health system is based on the French system, with most of the funding provided by the French government. This system has evolved from a labor-based Bismarckian system to a mixed public-private system (4). The public system insures coverage and access to all levels of health care available to all residents in French Polynesia. The private system is voluntary and is mainly used to cover copays for usual care, balance billing, vision and, dental care which are minimally covered by the public sector.

Healthcare facilities in some areas of French Polynesia may be less developed or accessible than in most Western countries. Although, there have been improvements on health care, some islands still lack resident doctors (17). Thus many Islanders still believe and practice old indigenous medicine, despite the recent advances in medicine. Healing practices and techniques include herbal baths, massage, cupping herbal remedies and healing rituals (17).

Legends

See Also

Works

Sources

External Links

Images

- Education in French Polynesia. (n.d.) Retrieved December 03, 2016, from http://snorlandfrenchpolynesia.weebly.com/politics--economy.html

- French Polynesia. (2015). The ARDA. Retrieved December 03, 2016, from http://www.thearda.com/internationalData/countries/Country_85_1.asp

- French Polynesia. (2016, July 12). Retrieved December 03, 2016, from http://www.worldatlas.com/webimage/countrys/oceania/pf.htm

- J. (n.d.). Tahiti By Janie. Retrieved December 03, 2016, from https://www.emaze.com/@AIRQZIWR/Tahiti-By:-Janie

- Joly, S. (n.d.). [Digital image]. Retrieved December 2, 2016, from http://www.tahiti-tourisme.org/

- Page, R. (2014) [Digital image]. Retrieved December 2, 2016, from http://www.bora-bora-insider.com/bora-bora/wedding-reception-with-himaa-maa-tahiti-the-tahitian-feast.html

References

- Ager, S. (2016). Tahitian (te reo tahiti/te reo Māʼohi). Retrieved October 12, 2016, from http://www.omniglot.com/writing/tahitian.htm

- Autonomous but French. Retrieved September 19, 2016, from http://www.globalpropertyguide.com/Pacific/French-Polynesia

- Current Local Time in Taiohae, Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 25, 2016, from https://www.timeanddate.com/worldclock/france/taiohae

- Country Health Information Profiles [PDF].(n.d.) 2011. World Health Organization.http://www.wpro.who.int/countries/pyf/8FRPpro2011_finaldraft.pdf

- Dunford, B., Ridgell, R., & Ridgell, R. (1996). Pacific neighbors: The islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia. Honolulu, HI: Bess Press.

- Education System in Polynesia. (2012). Class Base. Retrieved November 9, 2016 from http://www.classbase.com/countries/French-Polynesia/Education-System

- Food. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2016, from http://www.sea.edu/spice_atlas/food_atlas/imported_foods_obesity_and_health_in_french_polynesia

- Food in French Polynesia. (n.d.). Yestahiti. Retrieved October 18, 2016, from http://www.yestahiti.com/tourism_information/food-french-polynesia

- French Polynesia. (2015). The ARDA. Retrieved September 27, 2016, from http://www.thearda.com/internationalData/countries/Country_85_1.asp

- French Polynesia. (2016). Retrieved October 12, 2016, from https://www.ethnologue.com/country/PF

- French Polynesia. Retrieved November 21, 2016, from http://www.everyculture.com/Cr-Ga/French-Polynesia.html#ixzz4KiDOxvTC

- French Polynesia. (n.d). Countries and Their Cultures. Retrieved September 28, 2016, from http://www.everyculture.com/Cr-Ga/French-Polynesia.html

- French Polynesia. (n.d.). Retrieved September 13, 2016, from http://www.everyculture.com/Cr-Ga/French-Polynesia.html

- French Polynesia. Retrieved September 19, 2016, from http://www.everyculture.com/Cr-Ga/French-Polynesia.html#ixzz4KiDOxvTC

- French Polynesia- History and Culture. (2015). Retrieved October 25, 2016, from: http://www.iexplore.com/articles/travel-guides/australia-and-south-pacific/french-polynesia/history-and-culture

- Education System in Polynesia. (2012). Class Base. Retrieved November 9, 2016 from http://www.classbase.com/countries/French-Polynesia/Education-System

- Health and Health care of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander American. (n.d.). Retrieved November 21, 2016, from http://web.stanford.edu/group/ethnoger/nativehawaiian.html

- H. (2013). Savoring French Polynesia Through Its Five Essential Trees - Epicure & Culture. Retrieved October 18, 2016, from http://epicureandculture.com/savoring-french-polynesia-through-its-five-essential-trees/

- Hospitality of Tahitian & Polynesian people. Retrieved September 19, 2016, from http://www.tahiti-tourisme.co.uk/about-tahiti/culture/hospitality/

- Hospitality of Tahitian & Polynesian people. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2016, from http://tahitinow.com.au/about-tahiti/culture/hospitality

- Kiste, R. C., Suggs, R. C. & Kahn, M. (2011, September 9). Polynesian Culture. Retrieved September 13, 2016, from https://www.britannica.com/place/Polynesia

- Juliff, L. (2016, May 19). What’s it Like to Travel in French Polynesia? Retrieve October 25, 2016, from http://www.neverendingfootsteps.com/whats-it-like-travel-in-french-polynesia/

- Language. (n.d.). Retrieved October 12, 2016, from http://www.frommers.com/destinations/french-polynesia/271213

- News, B. (2016, April 14). French Polynesia territory profile. Retrieved September 05, 2016, from http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-16492623

- Rasmussen, W. (2010, April 6). Island Time. Retrieved October 25, 2016, from: http://www.sandiegomagazine.com/San-Diego-Magazine/Travels/April-2010/Island-Time/

- Religions. (2015). The Tahiti Traveler. Retrieved September 27, 2016 from http://www.thetahititraveler.com/general-information/society/religion-churches-and-temples/

- Pacific Islander Diet. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2016, from http://www.diet.com/g/pacific-islander-diet

- Polynesian Tattoo History. (n.d.). Retrieved September 13, 2016, from http://www.apolynesiantattoo.com/polynesian-tattoo-history

- Tahiti History and Culture. (n.d.). Retried September 13, 2016, from http://www.tahiti-tourisme.com/discover/tahitihistory-culture.asp

- Tahiti- The Society Islands (n.d.). Retireved September 14, 2016, from http://www.polynesia.com/polynesian_culture/tahiti/index.html#Population

- The Cuisine Of French Polynesia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2016, from http://www.streetdirectory.com/travel_guide/217047/cars/the_cuisine_of_french_polynesia.html

- The definition of poi. (n.d.). Retrieved October 18, 2016, from http://www.dictionary.com/browse/poi

- The People. Retrieved September 19, 2016, from http://www.frommers.com/destinations/french-polynesia/271211

- The Polynesians and Their Habits. (2014). Retrieved October 25, 2016, from: http://tnt.pa-tahiti-tourplan.com/guide-2/discovering/the-polynesians-and-their-habbits/

- The World Factbook: French Polynesia. (n.d.). Retrieved October 05, 2016, from https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/fp.html

- Urban dictionary. (2014). Retrieved from: http://www.urbandictionary.com/define.php?term=island%20time

- West, F. J., & Foster, S. (2016, June 6). French Polynesia. Retrieved September 5, 2016, from /www.britannica.com/place/French-Polynesia/Government-and-society#toc54079