Florence Aby Blanchfield

Contributors

- Emily Carlson

- Stephanie Holdaway

- McKay Martin

- Wela Tulafale

Editors/Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University

Early Life

Florence Aby Blanchfield was born April 1, 1884 in Shepherdstown, Jefferson County, West Virginia. Her father, Joseph Plunkett Blanchfield, was born on a boat coming in from Ireland that had just arrived at an American harbor. He grew up in the Charlestown West Virginia and worked as a stone mason in Harper's Ferry. Her mother, Mary Louvenia Anderson, was born in Virginia. She was married to Joseph in Middletown, Virginia and worked as a nurse. Florence was born into a family with much medical influence. Her mother was a nurse and both of her sisters became nurses later on in life as well. She also had an uncle and her maternal grandmother who were both physicians (Yurtoglu, 2018).

Joseph and Mary had 9 children, some of whom died at birth or at a very young age. Their first child was an infant who was born and died July 11, 1875. They continued to grow their family as follows: Harry Lee b: 10 June 1876, Ernest Franklin b: 5 February 1878, Mary Elizabeth b: 10 September 1880, Albert Lloyd b: 7 September 1885, Covington Allen b: 24 February 1889, George Wilbur b: 15 August 1889, Ruth Grace b: 13 October 1892 (RootsWeb's World Connect Project: The Blanchfield Family Database). Her brother Ernest died at age 25 to smallpox. Albert and George both died of typhoid fever at ages 17 and 21 respectively. It is said that the illness and eventual death of a favorite brother is what influenced Florence to become a nurse. She originally was in school to become a teacher, but the doctor who worked on her brother convinced her to go into nursing instead. So although the family moved frequently, they resided in the village of Oranda in Shenandoah County long enough for her to attend local schools and the private Oranda Institute in 1898-1899 (Notable American Women, n.d.).

Florence had pretty, vibrant blue eyes and a lively personality. She was known as being kind and humorous. Her whit was quick however, and one would wonder if they really actually caught a small glimpse of it at times or not. She was a dedicated person who would make decisions and stick to them. Much of this could've been attributed to her early years growing up on a farm of 7 acres large where the family raised chickens, cows, and hogs. Her and her siblings had plenty of chores to do before and after school each day. Chores kept the children so busy that Florence once said "e didn't need to develop hobbies, we had work to do" (Encyclopedia.co, 2019).

Education and Early Career

Blanchfield graduated from Southside Hospital Training School for Nurses in 1906. She worked in Baltimore as a private-duty nurse and studied at the sanatorium of Howard Atwood Kelly, a key figure in the development of the field of gynecology and a professor of medicine (Campell, 1998) studying with Howard Atwood Kelly, at Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Blanchfield served in medical administration from 1909 to 1913. She worked as a director of SouthSide Hospital Training School for Nurses. At that time she also served as the superintendent of the fifty-six bed Suburban General Hospital in Allegheny County, Pennsylvania (Campell, 1998). She was operating room supervisor at South Side Hospital and Montefiore Hospital, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1909, she was superintendent of a training school at Suburban General Hospital, in Bellevue, Pennsylvania.

In 1913, she chose to expand her knowledge of nursing. She worked for a year in the Panama Canal Zone where she worked as an operating room nurse and an anesthetist at the Ancon Hospital. The Ancon Hospital played a very significant role in the Panama Canal project. As it is in a tropical area, "the control of yellow fever, malaria, and other tropical disease was essential for the successful completion of the Panama Canal" (Chaves-Carballo, 1999). The project was dangerous for its workers and costly to build. The completion of the project was a demonstration for the United States growing to be a world power (Panama Canal, History.com). Much of this was due to the forces at the Ancon Hospital, including nurses like Blanchfield.

The Hospital was previously run by the French at the time when they were attempting the project. It was then known as "L' Hospital Central du Panama" (Chaves-Carballo, 1999). It became the Ancon Hospital when the United States began working on the project in 1904. Florence arrived in 1913, one year before the project was completed.

The impact that sanitary practices, preventative measures taken to protect workers' health, and the excellent hospital caretakers like Florence Blanchfield at Ancon all had on this project is astounding. The number of workers that were sick per day decreased from the French's 333 per 1000 workers to 23 per 1000 workers (Chaves-Carballo, 1999). Based on this, and the sharp decrease in the death rate of workers (compared to the French-ran project), it is estimated that "71,370 human lives [were saved] during the building of the Panama Canal'. How proud Florence must have been to be a part of such a great American effort.

After Panama, she decided to expand her knowledge again attended business school for two years at Martin Business college in the United States. As she went to school she continued to work, now as an emergency surgical nurse for a large plant in the United States Steel Corporation near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. In 1916, Blanchfield changed positions yet another time and once again became superintendent of the nurses at Suburban Hospital in Bellevue.

Florence was very well rounded and had interests in many facets of the world, seen around this time of her attending business school. (Sicherman, 1993). She was a writer, crafting articles for publication relating to nursing in the military. She did not just write, but she took classes on writing and composition. She also took courses in public speaking. There is no doubt that her understanding of both writing and public speaking proved useful to her throughout her entire life. She was interested in cars, studying auto mechanics, but also interested in fashion, studying dress-making (Sicherman, 1993). Florence truly had a passion for learning.

The Army Nurse Corps

When World War I broke out in 1917, she enlisted in the US Army Nurse Corps (hereafter "ANC"), she joined the University of Pittsburgh Medical School unit, Base Hospital #27, and served as acting chief nurse, in Angers and Camp Coetquidan, France, from August 1917 to January 1919. She was assigned to many military hospitals. She returned to civilian life for a period after the end of the War and briefly worked at Suburban General Hospital. However, she was drawn back to active service and rejoined the ANC after only eight months in January 1920. She became a first lieutenant in June when ANC officers achieved ranks similar to army officers. However, they lacked the same authority, pay, or privileges. She traveled to many hospitals during her career in the peacetime military. She visited hospitals in Michigan, Indiana, California, the Philippines, Washington, D.C., Georgia, Missouri, and China before she was assigned in 1935 to the surgeon general's staff in Washington. Four years later she was promoted to the rank of captain and made the assistant to the superintendent of the ANC as the United States prepared for war.

As Assistant Superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps, Florence made many impressive changes that helped nursing staff and patient care. She first fought to help bring about standardization for army nurses, across the board. (De Witt, 1943, n.p.) With her policy in place, new army nurses were required to receive four weeks of training, both on nursing related to battle needs and on army policies. She overcame much opposition around this but eventually got the policy set in place. Florence knew that this would be beneficial as nurses at any station hospital would be able to follow a standard procedure (De Witt, 1943, n.p.)

Florence also worked hard to help the Army nurses under her earn credit for the things they learned in their ANC experience. She worked with the National League for Nursing Education and helped nurses to "have credit established for the special training [they] receive in the Army" (De Witt, 1943, n.p.).

As Assistant Superintendent, Florence also increased success levels with nursing recruitment by changing how Army nursing was viewed. Her philosophy was one of candidness. She felt like the best way to recruit was by showing not what the ANC needed, but rather by attracting nurses through showing what ANC nurses have done and accomplished (De Witt, 1943, n.p.). "She [believed] that the greatest public and professional interest [would] develop from the outstanding record Army nurses [had] already made", and said herself that realists in the army were preferred: women who wanted to be nurses, not women who were there for the excitement or romance of it all (De , 1943, n.p) Florence's new take on recruitment proved successful, as the recruitment level rose to 2,000 new nurses monthly, "[bringing] the Corps' membership to 32,000 by the year's end" (De Witt, 1943, n.p.). Florence worked tirelessly to make the changes she knew would be the best for the Corps she so cared about.

A Woman in Service

Blanchfield was called the "Little Colonel" by her peers because of her tiny 5' 1" stature but was a leader with enormous passion (Colonel, 2013). Her leadership began to bear its fruits when the ANC grew from 1,000 to about 57,000 nurses. From Europe, Africa, Asia, and the Pacific, army nurses served in all facets of war. She took it upon herself to travel to various battlefields to inspect the conditions that her nurses would be working in. Her decision to move nurses closer to the battlefield would benefit injured soldiers, allowing them to receive proper medical care quickly, but it came with a cost. Being closer to the crossfire and enemy lines made them more susceptible to death and imprisonment. A total of 201 nurses died during wartime service and eighty-three were taken as prisoners of war (Hanink, 2017). In 1945 after 1,600 of her U.S. Army nurses at the time had received honors for their service during the wars, Blanchfield received the Distinguished Service Medal.

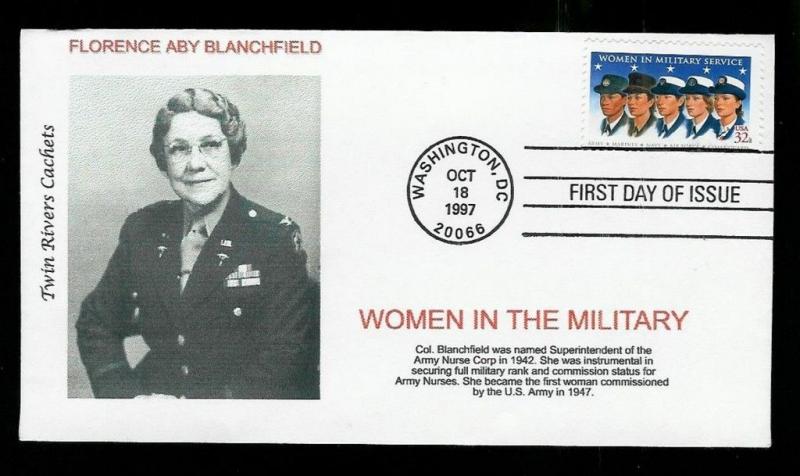

In 1942 a woman by the name Julia O. Flikke was Superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps, receiving a temporary commission as a colonel in the Army of the United States. Florence A. Blanchfield was assistant to Flikke at the time acting as Captain. She also received a temporary commission in the grade of lieutenant colonel. However, just because they wore the insignia of their grade did not mean that they were given the pay that was associated with having that level of a grade (Feller, 1995). Though they were making enormous sacrifices and saving the lives of servicemen, nurses were not given full military rank. Blanchfield continuously fought for change on this matter following her promotion from Captain to Lieutenant Colonel in 1942, arguing that army nurses should be granted the same pay, privileges, and rights as male commissioned officers (Florence, 2019).

She was granted temporary rank in 1944, but would not win full rank till 1947 when, with the support of congresswoman France Payne Bolton, the Army-Navy Nurse Act was passed (Blanchfield, 2019). Bolton toured military hospitals in England and France and was moved by the work that nurses were doing, this converted her into a strong supporter of the Army-Navy Nurse Act (Bolton, 2019). The act brought equal pay and privileges to nurses who were commissioned by the U.S. Army. This victory also earned nurses the right to marry and not be forced to resign as a result, as they were told to do before.

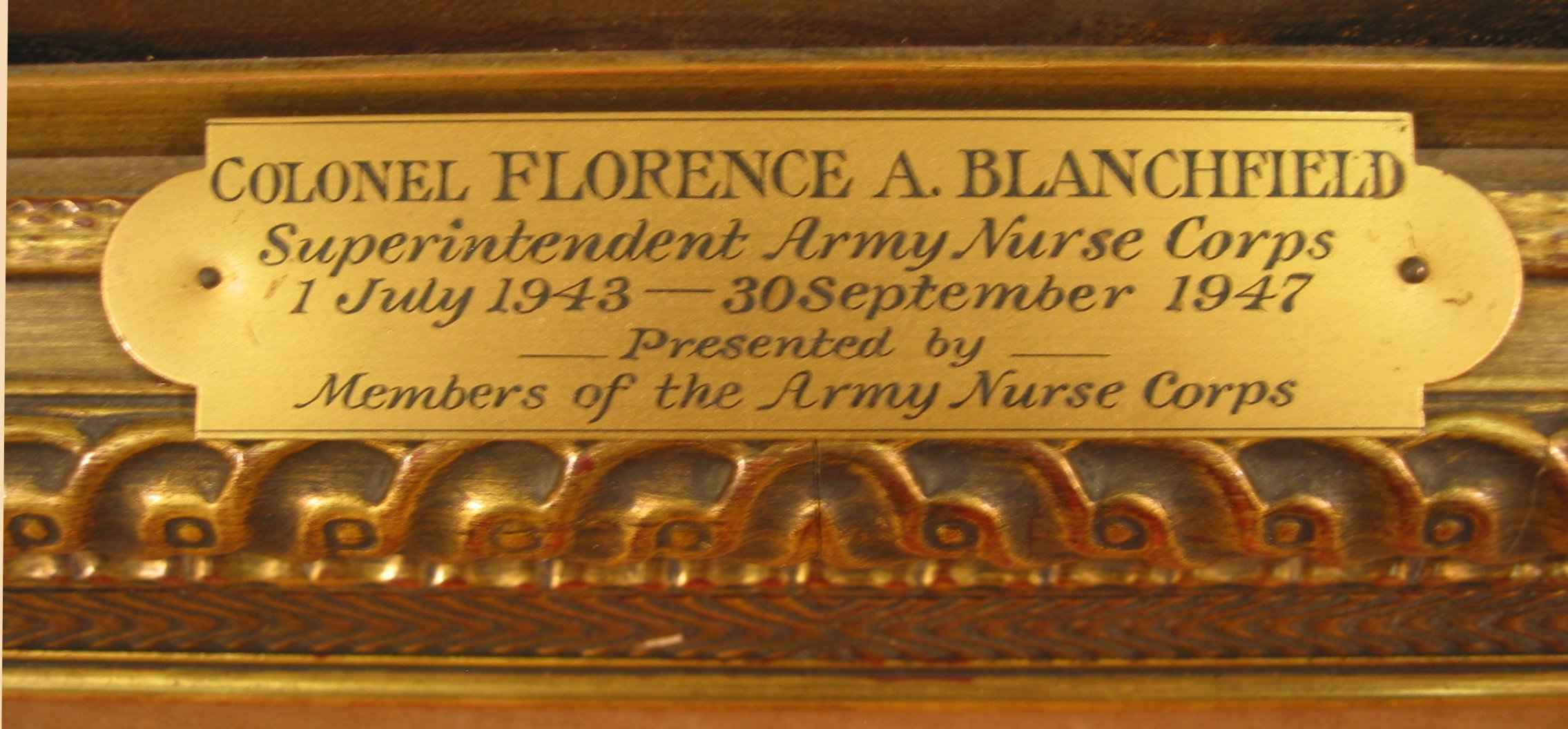

Blanchfield herself earned the first regular commission ever awarded to a woman in the U.S. Army, which was presented to her by General Dwight D. Eisenhower (Blanchfield, 2019). Even after her retirement that same year in 1947, she continued to influence equality for army nurses. She established specialized courses of study along with a program in army nursing administration laying the foundation for the future of the U.S. Army and its nurses (Florence, 2019).

Due to the illness of Col. Julia Flikke, Lt. Col. Florence A. Blanchfield became Acting Superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps. This made Blanchfield the seventh superintendent of the Army Nurse Corps (Feller, 1995). For her accomplishments while serving as Assistant Superintendent on behalf of the ANC, Florence Blanchfield was awarded several renowned titles including the Distinguished Service Medal in 1945 and the Florence Nightingale Medal by the International Red Cross (1951) as well as the West Virginia's Distinguished Service Medal (1963) (WikiVisually, 2019).

The Distinguished Service Medal is a military award of the United States Army that is presented to a person who is currently serving in any capacity with the United States military. The person awarded this medal is also distinguished personally by providing exceptionally outstanding service to the Government in a duty of great responsibility. It is a very prestigious title to have awarded (WikiVisually, 2019). Simply serving to the best of your abilities isn't enough to earn yourself this award. It is given out for beyond exceptional merit which is very telling as to the type of person Florence Blanchfield was and her efforts in the jobs she held.

The Florence Nightingale Medal was instituted in 1912 by the International Committee of the Red Cross. It is the highest international distinction a nurse can achieve and is awarded to nurses or nursing aides for "exceptional courage and devotion to the wounded, sick or disabled or to civilian victims of a conflict or disaster" or "exemplary services or a creative and pioneering spirit in the areas of public health or nursing education" (International Committee of the Red Cross, 2003). For someone to have been awarded not one, but two of these types of medals is quite the accomplishment. It is made very clear that these aren't just given out for doing an extraordinary job in your duties, but to someone who is exemplary beyond their expectations.

Florence was also awarded by the army for her long-lasting support of women's athletics. Not just an advocate for women in nursing, Florence had a trophy named in her honor to recognize her support of women in sports as well. In 1956, "the all-army women's tennis singles championship trophy was named for her" (Campbell, 1998).

Blanchfield's Personality

In addition to the many professional accomplishments, Florence was a very warm and caring person. She always tried to better educate herself. She completed graduate courses at the University of California and Columbia University. Informally, she studied auto mechanics, an interest that resulted as a necessity because of the failure of several civilian mechanics to diagnose an engine problem for her. She eventually became an expert at engine repair.

Even though she found value in being able to diagnose and repair engines, the more traditional feminine arts of sewing and cooking always remained extremely important to Florence. When she was not in military uniform, she often made her own clothes and studied courses in making dresses. Even in the early years when she was a student, Florence met was able to meet all of her expenses by designing and making dresses for the other students in training. She always believed that children should be given chores around the house to help contribute, and as part of those chores, she believed that all girls should be taught to be able to both be adequate in sewing and cooking-regardless of whether they intended to be wives or if they thought they were going to pursue a career, she believed they must be properly prepared.

Colonel Blanchfield was an avid reader, especially enjoying books of biographies, science, travel, history, atlases, nutrition, and cooking. During extensive world travels, she collected bases and items of interest for family members and herself. Without children of her own, she devoted much of her care and attention to a favorite great-niece, Mary Louise Lane, who often spent the summer months with her. In later life, Colonel Blanchfield came to regard Miss Lane's outstanding federal nursing career as one of her most rewarding personal satisfactions (Bombard, 1988).

With as many ranks and distinguished honors Blanchfield received, many might wonder what type of personality she had. Was she was strict or easy-going? Did she appreciate fun and humor or was she always serious? A fellow Army Nurse Corps (ANC) officer who worked with Colonel Florence Blanchfield during her time as Chief of the Army Nurse Corps counted the following story:

A short, sandy-haired woman entered the Pennsylvania Railroad Station in New York during WWII and made her way briskly to the ticket window. She was in her middle fifties and wore the uniform of an Army colonel. Two military policemen, assigned to observe military personnel en route to and from New York, to assist when necessary, and to arrest if indicated, looked at each other in amazement. This was not Colonel Oveta Culp Hobby of the Women's Army Corps-there was only one woman colonel authorized for them. This woman must be an imposter! They approached her as she neared the ticket window.

"Ma'am, could we see your identification card?"

"Certainly, Sergeant," she said quietly. She set her brief case on the floor and produced the regulation card with her picture and the name: Florence A. Blanchfield, Colonel, AUS. The first soldier examined the card and passed it on to the second, saying doubtfully: "It looks all right."

"It is all right," Colonel Blanchfield assured them. "You just haven't heard as much about the Army Nurse Corps as you have about the Women's Army Corps."

"Are you the head of the Nurse Corps?"

The Colonel nodded.

"re you catching a train?"

"I was," she smiled, "but I may have missed it now."

"We'll take care of it," one said. "You get her ticket, Joe, and bring her down. I'll go down and get a seat for her and hold the train."

He dashed off and the other got her ticket, picked up her small bag, and steered her through the crowd and down the stairway. When the "all aboard" sounded, the Colonel was settled in her seat and the two MPs were giving her an apologetic good-by (Vane, 2015).

This account says a lot about Blanchfield' humility, humor, pride, and poise. Her life's work led her to become an influential leader in the ANC, and throughout the rest of the Army, and she was proud of her achievements. Through it all, she never ceased to remember the importance of treating people with compassion and consideration, like the soldiers who had no idea who she was. She was humble in her position of power and never let it get the best of her. This is credited in huge part to her upbringing, being cared for by a compassionate mother who was a nurse, a humble stonemason father, and growing up in a tight-knit family. Equipped with these important attributes in her repertoire, Blanchfield was able to change the history of American nursing and influence those around her.

Her experiences as a bedside nurse also aided her when she made decisions as a Colonel. When she ordered for nurses to work at the frontlines of war, some of her nurses were hesitant to believe that they were needed there. She commented on the matter saying:

"Don't let anyone tell you that the combat zone is no place for nurses. It is definitely. Just see what a bedside nurse can do to boost the morale of any injured soldier. Just a pat on the head, blankets smoothed, and a woman's smiling face for a man to look up into - sometimes it's better than plasma" (Vane, 2015).

She knew the exponential worth of her nurses and the good that they were capable of doing for injured soldiers at war. Colleagues noticed her dedication to improving care for her patients and rights for her nurses, they were often inspired by her leadership and knowledge. Colonel Inez Haynes who later became Chief of the ANC talked about Blanchfield's work saying:

"She challenged us to do our utmost. She inspired and encouraged us to further the extent and depth of our knowledge of medical and nursing practice. She cared so much for quality nursing care, administration, and continuing education we learned to care and try. We identified with the goals she held out to us. She was a model. Rather than preach quality and leadership, she demonstrated quality and leadership" (Vane, 2015).

Blanchfield talked the talk and walked the walk. Though intimidating to all who did not know her, those who had the privilege of working with her knew her as a compassionate leader. They always had positive things to say about her. Her work paved the way for many nurses to be successful and for many lives to be saved. She is an example of what a leader should be and how they should treat others.

Blanchfield's Influence

Blanchfield will always be remembered for her service to her country and its people. Known for playing a big role in the movement for army nurse commissions, driving the formation of leadership in the ANC, and continuously fighting for better patient care at the front lines of war. Her colleagues envied her courage and drive, and her subordinates respected her every order without hesitation. Because of her recruitment efforts, many lives were saved during WWI and WWII. Even when 50,000 nurses were demobilized during WWII, she was determined to provide the best high-quality care possible to wounded soldiers (Vane, 2015).

Her goal was to influence all people, even far beyond battlefields. She said that each person should know "everything about things that affect our daily lived. . .as well as one's chosen field" (Vane, 2015). Wise words from one who lived and saw so many things. Her influence lives on today at the Blanchfield Army Community Hospital where women continue to lead and command the functions of this great hospital.

Many have seen success because of Blanchfield's history-changing efforts. They serve in leadership positions and add to the success of the military as a whole. One successor at Blanchfield Army Community Hospital (BACH), Lt. Col. Laura Dawson, who is currently serving as the Chief of Department of Surgery at BACH said "The Army has gone out of their way to set a success track for women who serve, women have continued to succeed, advance and expand what they are doing." Fruits of the labor that was started decades ago by Blanchfield herself (Hemingway, 2016).

Many generations of ANC leaders and army nurses that have followed in the footsteps of Blanchfield recall her success in healing the wounded in WWII and strive to uphold her legacy to the fullest (Hemingway, 2016).

Later Life

Culminating a career of unparalleled nursing service, Colonel Blanchfield retired from active duty on September 30, 1947. Her devotion toward making the profession of nursing better, enabled her to remain an irreplaceable adviser to succeeding chiefs of the Army Nurse Corps and the Office of the Surgeon General throughout her retirement. In retrospect, the Colonel's expert leadership and ingrained administrative skills had allowed expansion of the Corps from a few hundred nurses to many thousands of desperately needed caregivers. The personal impact of this achievement was known by the many soldiers wounded in battle and their grateful families on the home front. Ultimately, the overall impact of salvaged lives and return of soldiers to duty was support of victory -- the victory of winning the second World War.

Florence was involved in nursing for many years. After her retirement in 1947, she continued to work steadfastly within the world of nursing that she so loved. She decided to use her expertise from a lifetime of experience within the Corps to record some of the progress and changes seen throughout decades. She collaborated with Mary W Standlee to create a detailed manuscript history of the Army Nurse Corps. Together, the two worked for a few years traveling and compiling to create their complete history of the Corps. In 1950, Blanchfield and Standlee released Organized Nursing and the Army in Three Wars, discussing everything from winter in the wars to recruitment campaign methods (Sischerman, 1993).

Over a decade later, in 1964, Colonel Blanchfield was asked what her interests were then, to see if they had changed at all, after time had passed. At 80 years old, Blanchfield replied: "They are the same as ever, an intense interest in the nursing service, its professional progress; the broadening educational field . . . together with the art of nursing" (Sischerman, 1993).

In the later years of her life, Colonel Blanchfield lived in Washington D.C., with her sister Ruth, and her brother-in-law. Colonel Blanchfield suffered from heart disease and became a patient in Walter Reed Army Hospital for several weeks preceding her death. She died in 1971 on May 12th -- ironically, the date of Florence Nightingale' birth. With full military honors and in accordance with her Protestant faith, she was buried in the Nurses' Plot of Arlington National Cemetery (Bombard, 1988) .

In 1978, ANC leadership began a drive to commemorate Blanchfield by naming the new hospital at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, in her honor. This was due to the efforts of a successful letter writing campaign headed up by army nurses overwhelmed the senior commander at Fort Campbell. The Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield Army Community Hospital was dedicated in her memory on September 17, 1982 (Pierce, 2017).

References

- Blanchfield, Florence (1884-1971). Retrieved from https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and- maps/blanchfield-florence-1884-1971

- Bombard, C. F. (1988). The Soldiers' Nurse: Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield. Minerva, 6(4), 43-49.

- Campbell, D. (1998). Florence A Blanchfield. Retrieved from http://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Blanchfield_Florence_Aby

- Chaves-Carballo, E. (1999). Ancon Hospital: an American hospital during the construction of the Panama Canal, 1904-1914. Military Medicine, 10(175), 725- 731.

- Colonel Florence A. Blanchfield 7th Chief, Army Nurse Corps. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://e-anca.org/History/Superintendents-Chiefs-of-the-ANC/Colonel-Florence- A- Blanchfield

- Cover Story: Florence Aby Blanchfield, 1882-1971. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.veteransadvantage.com/blog/military-vet-life/cover-story-florence-aby- blanchfield

- De Witt J. (1943) Women who nurse: Col. Florence A. Blanchfield RN, 6(10), 20-24 Retrieved http://search.ebscohost.com.ezproxy.uvu.edu/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ccm&A N=106554610&site=eds-live

- Dictionary of Virginia Biography (n.d.). Retrieved from https://www.lva.virginia.gov/public/dvb/bio.asp?b=Blanchfield_Florence_Aby

- Feller, C. M. (1995). Highlights in the History of the Army Nurse Corps. Retrieved from https: //history.arm y.mil/html/books/08 5/85-1/CMH_Pub_ 85-1. pdf)

- "Florence Nightingale Medal". International Committee of the Red Cross. 2003. Retrieved 25 June 2010. https://history.army.mil/html/books/085/85-1/CMH_Pub_85-1.pdf

- Notable American Women. (n.d.). Retrieved from https://books.google.com/books?id=CfGHM9KU7aEC&pg=PA84&lpg=PA84&dq=what siblings-death-influenced-florence- blanchfield&source=bl&ots=Ot1Mlaq3hr&sig=ACfU3U04-KyhLc2fXztMyNBC-3Oog- viYA&hl=en&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwj8gPHToaTiAhVDba0KHRB8DiwQ6AewBHoEC AcQAQ#v=onepage&q=what siblings death influenced florence blanchfield&f=false

- Panama Canal. (2015, August 04). Retrieved from https://www.history.com/topics/landmarks/panama-cana

- Pierce, J. R. (2017, September 15). Florence A. Blanchfield: A Lifetime of Nursing Leadership. Retrieved from https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/article/146061/hospital- medicine/florence-blanchfield-lifetime-nursing-leadership

- RootsWeb's WorldConnect Project: The Blanchfield FamilyDatabase, worldconnect.rootsweb.ancestry.com

- Sicherman, B. (1993). Notable American women: The modern period: A biographical dictionary. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Vane, B. (2015). Colonel Florence Aby Blanchfield, 1884-1971. The AMEDD Historian, 9, 4-7. https://silvercaduceusassociation.org/PDF/AMEDD-HistorianNo9.pdf

- Yurtoglu, N. (2018).http://www.historystudies.net History Studies International Journal of History, 10(7), 241-264