Mary Eliza Mahoney

Contributors

- Mary Hodgson

- Megan Keller

- Hailey Lefgren

- Julia Olsen

- Kimber Pattberg

Editors/Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University

The Early Years

Early Years

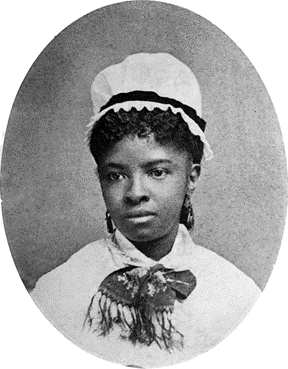

Mary Eliza Mahoney was born to Charles and Mary Jane Mahoney in the Dorchester neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts on May 7, 1845 (Ungvarsky, 2016). Her parents were freed African American slaves who were originally from North Carolina, yet shortly after getting married they left and moved to Massachusetts to avoid prejudice and discrimination (Tortorice, 2017). Mary was the oldest of three kids and had a younger brother, Frank, and a younger sister, Ellen. At a very early age, Mary learned from her parents the significance and importance of racial equality (Spring, 2017). This lesson proved to be very important throughout her life and is speculated to have driven her passion, profession, and political involvement in America (Ungvarsky, 2016).

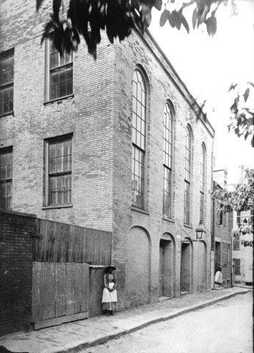

In 1850, the African American community in Boston was small, consisting of less than one percent of the population (Tortorice, 2017). Discrimination and prejudice existed in Boston, though it was not nearly as prominent and profuse as it was in the South during that same time period. There was not an integrated school in Boston until 1855, so prior to that the African American children of Boston attended school at the African Meeting House (U.S. Department of the Interior, 2021; Tortorice, 2017). Built in 1806, the African Meeting House was predominately used as a place of worship, as African Americans were �generally not allowed to sit in the nave with white congregants� (Garry, n.d.). School for Black children was held in the basement of the church (Garry, n.d.). Once segregated schools were outlawed in Massachusetts in 1855, the Phillips Street School, built in 1824 and named after Boston�s first mayor, John Phillips, became one of the first schools in Boston to become integrated (Tortorice, 2017). At the age of 10 years old, Mary attended the Phillips Street School in Boston from the first grade through the fourth grade (Ungvarsky, 2016).

Path to Nursing

It was while Mary attended school in her early years and throughout her teenage years that she developed an interest in nursing (Spring, 2017). Mary had a long history of nursing in her heritage. Many African American women, whether they were free or enslaved, would serve as untrained nurses, most often caring for other women (Ungvarsky, 2016). Mary followed in the footsteps of those who came before her and began helping to care for women and children.

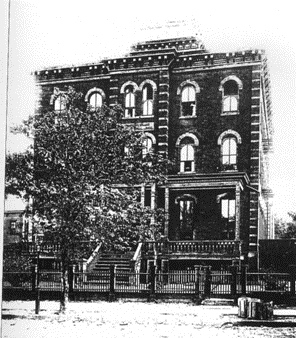

During her teenage years, Mary worked at the New England Hospital for Women and Children (Spring, 2017). Founded in 1862, the goal of the fully female-staffed hospital was �to provide patients with competent female physicians, educate women in the study of medicine, and train nurses to care for the sick� (Wikipedia, 2021). Mary worked in the New England Hospital for 15 years, during which her passion and interest in nursing continued to grow (Ungvarsky, 2016). She had many jobs while working at the hospital which included being a washerwoman, a janitor, a cook, and she even worked as a nurse�s aide (Ungvarsky, 2016). While working as a nurse�s aide, Mary learned a great deal about the nursing profession, which only continued to fuel her personal desire of becoming a professional nurse herself (Spring, 2017).

Nursing Education

Getting into nursing school was not an easy task. Requirements for acceptance into the program at the New England Hospital included being between the ages of 21 and 31 years, having a good reputation of character, and being healthy and strong (Chayer, 1954). Mary was 33 years old at the time she applied to the program, her age being outside the requirement. However, on March 23rd, 1878, Mary was accepted into the formal nursing program at the New England Hospital school, the same hospital she had been working at for 15 years (Petiprin, 2020). At the time, many nursing programs existed in the country but none of them accepted African American women (Tortorice, 2017). It is largely assumed that her acceptance was based on the years of hard and trustworthy work she put in at the hospital. Mary�s acceptance into nursing school is an achievement that marks a unique moment in history, as Mary was the first African American woman to be accepted into a nursing program in the United States.

It is said that Mary was very small, weighing only ninety pounds, yet she was full of courage and energy, which would help her in completing school (Mary, 1954). Mary�s schooling was a sixteen-month program, consisting of sixteen-hour days, seven days a week (Chayer, 1954). Students were under the direction of Dr. Crawford and Dr. Marie Zakrzewska, women physicians who had fifteen years combined of teaching experience (Chayer, 1954). In order to pay for their calico dresses and felt slippers, the school gave each student three dollars per week, which is equivalent to $90 today (Chayer, 1954). The first twelve months of school were spent on the medical, surgical, and maternal wards (Chayer, 1954). Days consisted of tasks including cooking, washing clothes, ironing, cleaning, and caring for the sick (Mary, 1954; Chayer, 1954). Students would be assigned complete care of six patients on a specific ward, with the assistance of a head nurse who had previously graduated (Chayer, 1954). The last four months were spent on their own, giving care in family�s homes in the community to prove students were competent in what they had learned (Chayer, 1954). When students were not on ward duty, they attended day long lectures. (Hurst, 2019).

Mary�s nursing program was rigorous, and out of the forty students who applied, nine withdrew themselves, thirteen were unsuitable, eighteen were accepted for trial, nine were kept after trial, and only three students received diplomas (Chayer, 1954). Mary was one of those three. She received her diploma on August 1st, 1879, along with two white girls (Chayer, 1954). This was an accomplishment for all of these women, but especially for a Black woman in the 1800�s due to segregation, prejudice, and racism that still existed in the country. Mary�s courage and determination as the first Black woman to be accepted into nursing school influenced other Black women to follow in her footsteps. In fact, Mary�s younger sister, Ellen, also took the sixteen-month course, but in the end she did not receive a diploma due to twenty missed questions on her examination (Chayer, 1954).

Due to Mary�s precedent of being accepted to and completing the nursing program at the New England Hospital for Women and Children, other Black women were able to apply to and be accepted into the same program. Mary�s profound and skillful academic and practical performance seemed to have helped create a culture of tolerance at the school as the lists of students made no mention of race. Students were expected to attend class, be prepared for exams, and work hard regardless of the color of their skin (Chayer, 1954). Mary�s dedication to nursing, her kind soul, and her work ethic made it possible for other Black women to follow in her footsteps by gaining the opportunity for an education in which they could contribute to the world through the healing art of nursing (Chayer, 1954).

Nursing Career

After graduation, Mary decided against a career in public nursing because of the intense discrimination that predominated American culture during the late 1800s (Spring, 2017). Instead, Mary decided to focus on becoming a private nurse and was hired by mostly white, wealthy families up and down the east coast. Mary registered in a directory of nurses at the Boston Medical Library, which was established in 1875 in order to condense and organize medical texts, as a way to market herself as a private nurse (Tortorice, 2017). Mary was the only Black individual that was a part of this directory (Tortorice, 2017). Mary began her career making $1.50 a day and $8.00 a week, but her rates increased to $2.50 a day and $15 a week by 1892 (Tortorice, 2017). A dollar in 1890 is worth $30 today, so after her rate increase Mary�s wages would be equal to $75 a day and $450 a week in the year 2021. Mary worked for individual families, and much was expected out of private-duty nurses. They would often have to work 24 hours per day for the length of their employment. Private duty nurses were also expected to:

�stay quiet so they wouldn�t disturb the patient or family, be cheerful, and never disagree with the client. Private-duty nurses depended on referrals for future work, so they had to keep every patient, family, and doctor happy. If a private-duty nurse had experience and a good reputation, she could be selective about her work and take time off when needed. Otherwise, a nurse had to take every job that came along in order to make a living� (Tortorice, 2017).

Mary developed a strong reputation among her clients for her �efficiency and calm approach,� and potential clients called from many states including Massachusetts, New Jersey, Washington, and North Carolina (Paton, 2019). Some reviews left in the Nurses� Directory about Mary included, � �no faults noticed,� �excellent nurse,� and �good temper, discretion, and loyalty� � (Tortorice, 2017).

Mary was well known in her nursing practice for her patience and caring bedside manner (Spring, 2017). Mary often developed deep relationships with the families and patients she cared for, in particular the Armes family. Mary was frequently employed by the Armes, and during her time with them she cultivated endearing friendships. Mr. Armes is known to have said, � �I owe my life to that dear soul,� � and later in Mary�s life she listed him, along with her sister, as her next of kin (Chayer, 1954). Mary�s demeanor and �calm, quiet efficiency instilled confidence and trust,� in the patients she cared for, and people would �sing her praises� all around Boston (Chayer, 1954).

Mary helped establish the professional nature of the nursing profession. Before nursing schools were established, nurses were largely formally untrained, and their responsibilities included domestic chores (Ungvarsky, 2016). Clients were familiar with this idea of a nurse and would try to treat Mary as such. In response, and while still adequately caring for her patients, Mary would not eat with household servants and set boundaries with her clients to avoid being treated as a household servant (Ungvarsky, 2016).

Personal Life

Mary insisted on keeping her life private, therefore, not much is known about Mary Eliza Mahoney�s personal or romantic life. At some point, an unknown physician asked for Mary�s hand in marriage, but the physician then ended the engagement, deeply affecting Mary (McAfee, n.d.). After this brief courtship, Mary remained single for the rest of her life and additionally never had children. There is no telling exactly why Mary never married or entered into a relationship after her courtship with the unknown physician ended. However, there are many potential factors as to why this was the case. Mary could have been traumatized from her previous engagement and had no desire to marry or enter in a relationship after its ending. Additionally, Mary was deeply religious. Due in part to this, Mary saw nursing as a calling in which she devoted herself to. Lastly, Mary started her nursing career at an advanced age, and the life of a private nurse was not conducive to having a family as nurses were in the service of the families they served for long hours. Instead of marriage or relationships, Mary focused her time on caring for patients in need as a private nurse.

Mary was a devout Baptist, and she would attend church regularly. She could be found attending the People�s Baptist Church, which was built in 1805 and was the first African Baptist church in the area, in Roxbury, Massachusetts (McAfee, n.d.). It was believed that Mary�s religious background was one of the things that helped her decide to pursue a career in nursing. �Mahoney is said to have been quiet, competent� have a strong faith in God� [and] very likely believed her work was a religious calling. Caring for the sick was viewed as charitable, humanitarian work that complimented what it means to be a good Christian� (McAfee, n.d.). Mary�s work was her life, and her religion and beliefs only added to her commitment and devotion to caring for those in need, as �nursing was a way to put one�s faith into action and have a direct impact on the lives of the needy and downtrodden� (McAfee, n.d.).

Influence of Society�s Perception of Minority Nurses

During her 40�s, Mary continued to work as a private nurse and would show her patients kindness and treated them like family. This helped build her reputation and made it so others wanted her to be their nurse. One of the reasons Mary decided to be a private nurse was so that she could focus on the individual patient and their needs (Spring, 2017). Those she took care of started having a different view of African Americans because of Mary�s dedication to her patients and the great care she provided. �Wherever she went, Mahoney left people impressed with her skills, caring attention, and professionalism� (Tortorice, 2017). Mary had a motto which helped in her dedication. She would say, �work more and better the coming year than the previous year� (Tortorice, 2017). This would push her into being better and doing better in her nursing and care for her patients than she did previously. Her motto, dedication, and hard work only propelled her career as a nurse. More and more people were hearing her good praises, and she became high in demand up and down the east coast.

In addition to caring for people through nursing, Mary had another ambitious goal, which was to change the way people thought about minorities in the nursing profession (Wisconsin Center for Nursing, n.d.). Though slavery was abolished in Massachusetts in 1783, prejudice and racism of African Americans persisted. Some people accepted this minority group, but much of the population did not. Professionals from the North were mostly willing to employ Black nurses because nursing was viewed as a position of servitude, and Black nurses fit that mold (The State, 1996). As a professional, a woman, and an African American, Mary wanted to �abolish any discrimination in the nursing field� (Wisconsin Center for Nursing, n.d.). Mary knew that she could alter people�s perceptions and biases of Black nurses through her own knowledge, expertise, and professionalism. Through her dedication of care to her employers, skills, and preparedness, Mary hoped to change the way patients and families thought of minority nurses (Wisconsin Center for Nursing, n.d.).

Nursing Associations

Throughout her career, Mary Mahoney was a part of many notable nursing associations. In 1896 and at the age of 51, Mary joined the Nurses Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada (Spring, 2017). The Nurse Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada was renamed in 1901 when New York broke away from Canada and was renamed the Nurses� Associated Alumnae (Purdy, n.d.). The name went through one more change in 1911 and since then has been known as the American Nurses Association, or the ANA (Purdy, n.d.). The organization was founded in New York City in 1896 and became an important resource for nurses to help with establishing a code of ethics, promoting financial needs, and establishing state laws to ensure licensure for nurses (Purdy, n.d.). Each individual state was in charge of licensing (Purdy, n.d.). New York, New Jersey, Virginia, and North Carolina were the first states to enact bills requiring registration of qualified nurses (Purdy, n.d.). From there the title �registered nurse� was created, but only those who had the qualifications could use the professional title (Purdy, n.d.). Mary was one of the first Black members of this association and advocated for more Black women to join, but unfortunately the majority of the members were white and were not very welcoming to those of color (Mary Elizabeth, 2021).

In response to this treatment, Mary, along with Martha Minerva Franklin and Adah B. Thoms, sought out a new hope (Mary Elizabeth, 2021). Martha Minerva Franklin was the only Black graduate in her class at the Woman�s Hospital Training School for Nurses in Philadelphia and she knew that Black nurses needed support and help to increase their professional status (Martha, n.d.). Adah Belle Thoms was also the only Black student to graduate from her nursing school at the Women�s Infirmary and School of Therapeutic Massage (Adah, 2020). Adah felt the effects of racism as she was acting director of the Lincoln Hospital and Home School of Nursing but was never able to receive the official title of director because of her color (Adah, 2020). These three women wanted something better for their fellow nurses of color and the future nurses of color who would walk in their footsteps.

In 1908, Mary became a co-founder of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN) along with her courageous colleagues, Martha Minerva Franklin and Adah B. Thoms (Mary Elizabeth, 2021). The NACGN served to promote �the standards and welfare of Black nurses� as well as tackle racial discrimination in the profession and �win integration of Black nurses into nursing schools, nursing jobs, and nursing organizations� (African American History Online, n.d.). Mary was a speaker during the first national NACGN convention held in Boston in 1909 (Spring, 2017). She spoke on the inequalities for Black individuals to be educated as nurses and encouraged a demonstration at the New England Hospital (Petiprin, 2020; Spring, 2017). Mary was also elected to be the group�s national chaplain (Spring, 2017). This gave her the benefit of being a lifetime member of the NACGN who was exempted from dues (Hurst, 2009). Mary was very involved in these groups, and it was said about her that, �Miss Mahoney was a remarkable person�She seldom missed a national nurses� meeting� (Chayer, 1954).

Members of the NACGN lobbied in several states throughout the U.S. for legislation allowing Black nurses to attend school; practice in homes, clinics, and hospitals; join military forces; and be allowed in state nurses associations. Their efforts were so successful that in 1951 the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses voted to dismantle themselves in order to be fully integrated with the American Nurses Association. Mary�s achievement in creating this organization for the betterment of all Black nurses is commemorated every other year in the American Nurses Association by the Mary Mahoney Award. Established in 1936, the Mary Mahoney Award is given to nurses who make significant contributions in �advancing equal opportunities in nursing for members of minority groups (African American History Online, n.d.). The NACGN was responsible for distributing this award annually until the organization dissolved in 1951, at which point the ANA assumed responsibility for giving the award (Ungvarsky, 2016).

Howard Orphanage Involvement

Another lifetime achievement of Mary was her involvement with the Howard Orphan Asylum for Black Children. The orphanage was created for children whose mothers moved north to find work. Oftentimes Black women would be employed in white people�s homes, but the employers were not willing to house and support the children of the women they employed. These children ended up homeless or working for very low wages. The Howard Orphan Asylum in Brooklyn, New York was created by African Americans for African American children, providing for them safe shelter, food, and education (Evans, 2020). Mary served as the director of the orphanage from 1911 to 1912 (African American History Online, n.d.).

Advocacy

Throughout history, African Americans were not always treated with the most respect. As society has changed and people are becoming more aware of the wonderful things these people are doing, there is not as much disrespect for them. Mary experienced this disrespect, but she pushed past it and made others see that she was a wonderful person. After slavery was abolished, there were African Americans who felt that they needed to be recognized for their contributions to civilization (The Library of Congress, n.d.). The Association for the Study of Negro Life and History (ASNLH) � now called The Association for the Study of African American Life and History (ASALH) � created Negro History Week in 1925 (The Library of Congress, n.d.). During this week, they would celebrate African American life. In 1976, the celebration was expanded to last a whole month. This celebration is now called Black History Month and occurs during the month of February every year. Mary Eliza Mahoney has been recognized for her contributions to African American history on many Black History Month websites and articles. She has been recognized as �the first professionally trained African American nurse in the United States. In addition to her dedication to the nursing profession, she is known for promoting equality for African Americans and for women� (Scott, 2019). She was also seen as one of those nurses who �dared to break through cultural norms to offer care to their communities� (Celebrating Black History, n.d.). Mary made such an impact and paved a way for many African Americans that it was impossible for her not to be recognized during Black History Month.

Mary not only made a considerable contribution to Black History Month, but she also has helped set a path for women. Before women�s suffrage, only men were allowed to vote for anything, including who would become the president of the United States. Because Mary had such a strong conviction for women's equality, she made it possible for women to participate in voting to this day. Election day is the day when senators, congresspeople and the president are voted in by the men and women of the country. Mary was one of those determined women who made it possible for all women to vote. She helped bring equality to all women who came after her.

Retirement

Mary retired from nursing after over 40 years of service (Spring, 2017; McAfee, n.d.). However, retirement did not stop Mary from serving individuals and she focused her energy from serving patients to acting as an advocate for minority groups. Mary was actively involved in supporting women�s suffrage (Wisconsin Center for Nursing, n.d.). The 19th Amendment was ratified on August 26, 1920, giving women the opportunity to vote (Spring, 2017; Biography, 2020). At this time in 1920, at the age of 76, Mary became one of the first women to register to vote in Boston, Massachusetts (Wisconsin Center for Nursing, n.d.; Tortorice, 2017). Not only was this a big step for women during her time but would impact women for many years to come.

In her later life, Mary continued to be active in the nursing associations she was a part of. The last National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses conference Mary attended was in 1921 (McAfee, n.d.). Mary had the opportunity, along with other nurses who were guests of the Freedman�s Hospital Alumnae Association, to visit the White House and meet with the President of the United States at the time, President Warren Harding (McAfee, n.d.).

Death and Legacy

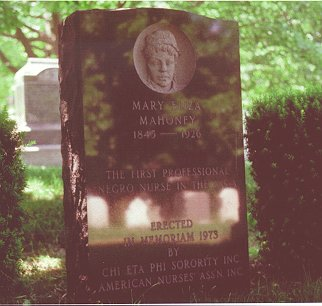

In 1923 Mary Mahoney was diagnosed with metastatic breast cancer and battled the illness for three years before it would take her life on January 4, 1926, at the age of 80. She passed away in the very hospital she did her nursing training back in 1878 at the New England Hospital for Women and Children after having entered the hospital on December 7, 1925 (Ungvarsky, 2016). Her body was buried in her home state at the Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett, Massachusetts (Ungvarsky, 2016). The legacy she left has lived on for generations, and her headstone reflects her life achievement, reading, �The First Professional Negro Nurse in the U.S.A.� (Tortorice, 2017).

Her contributions to the nursing field have been recognized, and the Mary Mahoney Award, which was established ten years after her death, recognizes women who contribute to racial integration in nursing (Ungvarsky, 2016). One of the recipients of the award visited her gravesite in 1968 and was unsatisfied with its condition. This individual, Helen S. Miller, began a campaign to have a larger marker placed to acknowledge Mary�s accomplishments. With the help of the national African American sorority Chi Eta Phi and the ANA, enough money was raised for a new grave monument (Ungvarsky, 2016). The new stone was placed in 1973 with many recipients of the Mary Mahoney Award and members of Mary�s extended family in attendance.

Mary was admitted to the ANA�s Nursing Hall of Fame in 1976 and the National Women�s Hall of Fame in 1993 (Ungvarsky, 2016). Mary Mahoney Memorial Health Center in Oklahoma City and the Mary Eliza Mahoney Dialysis Center in Boston were both named in Mary�s honor (Mary Mahoney Facts, 2021). Mary is honored because of her courage entering nursing school as the first African American, her exceptional performance as a student, her expertise and tenderness as a practitioner, for being an outstanding citizen, and for being an enthusiastic local and national professional organization worker (Chayer, 1954).�A pioneer of nursing, Mahoney dedicated her life to her work and advancing the cause of African-American women in the profession. That is not to say that work is complete; there will always be a need for pioneers like her�people daring enough to be the first at something and pave the way for others to follow� (Tortorice, 2017).

References

- Adah Thoms, Nursing pioneer born. African American Registry. (2020, September 14). https://aaregistry.org/story/adah-thoms-nursing-pioneer-born/

- African American History Online (n.d.) Mary Elizabeth Mahoney. https://www.africanamericanhistoryonline.com/maryelizabethmahoney.php

- American Association for the History of Nursing. (n.d.) Mary E. Mahoney: 1845-1926. aahn.org/mahoney

- Biography (2020, July 9). Mary Mahoney. Biography.com. https://www.biography.com/activist/mary-mahoney

- Celebrating Black History Month - Mary Eliza Mahoney (n.d.). Black Nurses Rock. https://blacknursesrock.net/2021/02/01/lets-celebrate-black-history-month-mary-eliza-mahoney/

- Chayer, M. (1954). Mary Eliza Mahoney. The American Journal of Nursing, 54(4), 429-431. doi:10.2307/3460941

- Evans, R. (2020, June 11). The Howard colored orphan asylum: New York's first black-run orphanage. New York Public Library. https://www.nypl.org/blog/2020/06 /11/howard-colored-orphan-asylum-new-york

- Garry, J. (n.d.). African Meeting House. Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/ African-Meeting-House

- Hurst, R. (2009, March 28). Mary Eliza Mahoney (1845-1926). Black Past. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/mahoney-mary-eliza-1845-1926/

- Martha Minerva Franklin (1870-1968) 1976. American Nurses Association. (n.d.). http://ojin.nursingworld.org/FunctionalMenuCategories/AboutANA/Honoring-Nurses/NationalAwardsProgram/HallofFame/19761982/franmm5536.html

- Mary Eliza Mahoney, First Negro Nurse. (1954). Journal of the National Medical Association , 46(4).

- Mary Elizabeth Mahoney - First African-American Nurse. Wisconsin Center for Nursing. (2021, February 1). https://wicenterfornursing.org/mary-elizabeth-mahoney-first-african-american-nurse/

- Mary Mahoney Facts, Worksheets, BIOGRAPHY, life, Nursing & DEATH KIDS. KidsKonnect. (2021, June 18). https://kidskonnect.com/people/mary-mahoney/

- McAfee, V. (n.d.). Mary Eliza Mahoney: She Saw Her Calling as Nursing. https://ministryspark.com/wp-content/uploads/15-MaryElizaMahoney.pdf

- National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses Founded. African American Registry. (n.d.). https://aaregistry.org/story/national-association-of-colored-graduate-nurses-founded/

- Paton, F. (2019, February 19). Mary Eliza Mahoney: The First African American qualified nurse. Nurse Labs. https://nurseslabs.com/mary-eliza-mahoney/

- Petiprin, A. (2020). Mary Eliza Mahoney, first African American nurse. Nursing Theory. https://nursing-theory.org/famous-nurses/Mary-Mahoney.php

- Purdy, E. R. (n.d.). American Nurses Association. Encyclopaedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/American-Nurses-Association

- Scott, Gallen. (2019, March 1). Black History Month - Mary Eliza Mahoney. The Researcher's Gateway. https://researchersgateway.com/black-history-month-mary-eliza-mahoney/

- Spring, K. A. (2017). Biography: Mary Eliza Mahoney. National Women's History Museum. https://www.womenhistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-mahoney

- The Library of Congress. (n.d.). African American History Month. https://africanamericanhistorymonth.gov/about/

- The State of African Americans in Nursing Education. (1996). The Journal of Blacks in Higher Education, (13), 52-54. doi:10.2307/2963165

- Tortorice, J. (2017). Mary Eliza Mahoney: First African American Nurse. CEUfast Blog. https://ceufast.com/blog/mary-eliza-mahoney

- Ungvarsky, J. (2016). Mary Mahoney. Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia. https://ezproxy.uvu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=ers&AN=89407085&site=eds-live

- U.S. Department of the Interior. (2021). The Phillips School. National Parks Service. Accessed on May 21, 2021 from https://www.nps.gov/boaf/learn/historyculture/the -phillips-school.htm

- Wikipedia. (2021, July 26). New England hospital for women and children. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/New_England_Hospital_for_Women_and_Children

- Wisconsin Center for Nursing. (n.d.). Mary Elizabeth Mahoney, first African-American nurse. Wisconsin Action Coalition. Retrieved June 2, 2021, from https://wicenterfornursing.org/ mary-elizabeth-mahoney-first-african-american-nurse/