Vera Mary Brittain

Contributors

- Sara Allred

- Lezlie Bartholomew

- Julie Higginson

- Kendra Swensen

Editors/Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

Vera Mary Brittain

Vera Mary Brittain (December 29, 1893 - March 29, 1970) was a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) nurse during World War I (WW I). She is remembered through her memoir Testament of Youth in which she brings to life her experiences of the war. She is also remembered as a writer, activist, and feminist.

Early Life

Vera Mary Brittain was born December 29, 1893 in Newcastle-under-Lyme, Staffordshire, England to Thomas Arthur Brittain and Edith Bervon Brittain. Vera had one younger brother, Edward Harold Brittain, whom she was very close to throughout her life. When she was young, her family moved to Buxton in Derbyshire. Her father was a wealthy industrialist who owned paper mills in Hanley and Cheddleton. As a child, she attended a boarding school at St. Monica's in Kingsbury, Surrey where her Aunt Florence was a principal. Although St. Monica’s taught middle-class women stereotypical female accomplishments, it also provided classes in history and science (Davies, 2014). This school provided Vera with “a solid, well-rounded education rather than stressing purely social ‘feminine’ attainments” (Spongberg, 2005, p.73). In Testament of Youth, Vera remarks that she had an idyllic childhood growing up with her brother in the country (Brittain, 1994 ed, p.452).

Vera attended the Summer Meetings at Oxford which were part of their Extension Lectures in 1913. Here she heard J.A.R. Marriot’s lecture series and spoke with him at this time (Goldman, n.d.). It was after this meeting and her desire to become a writer that inspired her to attend Somerville College, Oxford (Brittain, 1982 ed, p.38). This was not the conventional expectation for a young lady at the time. It was expected that she marry and have children to fill her social role as a young English woman (Peace Pledge Union, n.d.). After finally getting her father’s permission, she began studying Math and Latin so she could pass the Oxford Senior exam and the Somerville scholarship exam (Brittain, 1982 ed, p.38). In 1914, she applied for, and was accepted at Somerville College, Oxford.

On August 4, 1914, Germany violated the Treaty of London by invading Belgium bringing Great Britain into the war. War had begun and Edward, Roland, and Victor all joined the military. Vera decided that she also wanted to be a part of the war effort and left Somerville College, Oxford to join the Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) as an auxiliary nurse (Davies, 2014).

WWI Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) Nurse

Vera responded to the outbreak of war with all the patriotic fervor that the war propaganda promoted (Gorham, 1996, p. 80). She was ready to adhere “to conventional definitions of duty, honour [sic] and heroism.” (Gorham, 1996, p. 81). While still at school, she wrote to Roland saying:

“I remember once at the beginning of the War, […] you described college as ‘a secluded life of scholastic vegetation.’ That is just what it is. It is, for me at least, too soft a job. . . . I want physical endurance; I should welcome the most wearying kinds of bodily toil.” (Brittain, 1980 ed, p. 140).

She volunteered with the British Red Cross where she learned first aid and did sewing for the war effort, but she wanted to be more involved. (Brittain, 1982, p. 92). Vera is listed as a famous volunteer on the British Red Cross website (British Red Cross, 2017).

On April 4, 1915, Vera encountered the Matron of Devonshire Hospital. She recalls this meeting in Testament of Youth saying: “Impulsively I attacked her and asked if she had any work to offer which I could undertake.” (Brittain, 1980, p. 140). The Matron gave her the task of darning socks until her mother was able to help her get a position as a nurse.

Up until WWI, female nurses were not often accepted in the British military. For the most part these women were sent to Belgium or France. But as things progressed they no longer had the option to continue to send resources (nurses) away from their own battle fronts. Vera signed on to be a Voluntary Aid Detachment (VAD) Nurse which means she was a civilian nurse contracted with the British military. Vera gained most of her training on-the-job and in the epicenter of the WWI hospitals treating and caring for maimed soldiers. These nurses were not well accepted by the professional nurses and were often given domestic labor jobs and rarely trained or permitted to change dressings or administer medications. The VAD nurses provided a range of services that included caring for sick, wounded, and convalescing soldiers under the direct supervision of trained nurses; however, the VAD’s did not receive the recognition of the trained nurses. Their jobs were often hard and they had very poor job security. The VAD nurses were routinely dismissed for minor infractions (BBC, 2014). Vera carried out her responsibilities with dignity. Like most young men and women at the time, she believed she was fulfilling her duty to her country (British Red Cross, 2017). In a letter to her fiancé, Roland Leighton, Vera described her feelings towards her nursing duties as follows:

"I can honestly say I love nursing, even after only two days. It is surprising how things that would be horrid or dull if one had to do them at home quite cease to be so when one is in hospital. Even dusting a ward is an inspiration. It does not make me half so tired as I thought it would either... The majority of cases are those of people who have got rheumatism resulting from wounds. Very few come straight from the trenches, it is too far, but go to another hospital first. One man in my ward had six operations before coming and is still almost helpless (Spartacus Educational, 2015)."

On June 27, 1915, Vera began working as a nurse at Devonshire Hospital in Buxton (Brittain, 1982 ed, p. 214). This was her first posting as a VAD nurse during WWI. She worked in Devonshire Hospital from June 1915 until the end of September 1915. She worked longer hours “than [were] normally required in many Army hospitals” (Brittain, 1980 ed, p. 164). In Testament of Youth she recalls, “I never completely overcame the aching of my back and the soreness of my feet throughout the time that I worked there, and felt perpetually as if I had just returned from a series of long route marches.” (Brittain, 1980 ed, p. 164). Although the work was long and hard, Vera didn’t mind. She viewed it as “satisfactory tributes to my love for Roland” (Brittain, 1980 ed, p. 164).

In October of 1915, she left Buxton and became “a full time VAD under contract with the British Red Cross society at a London military hospital.” (Gorham, 1996, 97). She began working in London where the conditions were far worse than in Buxton. In Buxton, she could go home at the end of a hard day’s work; in London however, she had to stay in a hostel with the other VAD nurses. Vera describes their residence as “... ‘a distant, ill-equipped old house’ whose cold bathroom and unreliable hot-water heater added to their miseries.” (Gorham, 1996, p. 106). She said, “Never, except when travelling, had I to put up with so much avoidable discomfort throughout my two subsequent years of foreign service as I endured in the centre [sic] of the civilised [sic] world in the year of enlightenment 1915.” (Brittain, 1982 ed, p. 209).

In addition to the living conditions, Vera was working over twelve hours a day. She was assigned to night shifts which she described as “a nerve-stirring business.” (Brittain, 1982 ed, p. 291). Her main duties were to make sure the patients were all right and to make hot chocolate and milk to give to the patients (Brittain, 1982 ed, p. 291). She also prepared dressing-trays and helped the trained nurses bandage wounds. In her book, Testament of Youth, she tells the reader of her first experience assisting with a leg wound dressing: “… a gangrenous leg wound, slimy and green and scarlet, with the bone laid bare – turned me sick and faint for a moment that I afterwards remembered with humiliation” (Brittain, 1980 ed, p. 211). She goes on to describe how it did not seem to affect the trained nurses. She said of the trained nurses, “There is something so starved and dry about hospital nurses – as if they had to force all the warmth out of themselves before they could be really good nurses.” (Brittain, 1980 ed, p.211). Many of her patients did not make it; one such patient was a man named Sapper Smith. Vera recounts her night round when at 7 o’clock Sapper Smith passed away; she felt that it was a merciful release from his pain and agony. Vera’s words of death were this “we ought to pray in our litany for deliverance from a lingering as well as from a sudden death. It is not death itself that presents such terrors to the mind, but dissolution, and when that begins before death” (Brittain,1982 ed, p. 233).

Vera worked in the London hospital until September of 1916 when she received orders to go to Malta. Before Vera arrived in Malta, there was a shortage of doctors and nurses and the patients coming in were overwhelming the staff. To relieve the pressure from incoming patients, more hospitals were built and supplied with staff to adequately sustain patient care. In September of 1916, Vera and other VAD nurses were sent to the island to help ease some of the strain (Darmanin, 2010). On September 24, 1916 she began her journey to Malta and arrived on October 7th (Brittain, 1982 ed, 328-331). Vera worked at the St. George Hospital in Malta, one of seven hospitals on the British Island (Claudel, 2015). Her work there was more relaxed than previous assignments in the hospitals in Britain (Acton, 2014). During this eased time, Vera and her fellow nurses were able to play tennis with the men that they helped care for and socialized with the other officers after. While on assignment in Malta, Vera received word that one of her close friends (Geoffrey) had died, and another unnamed friend was fatally wounded. After her service from September 1916 to May 1917 Vera returned home.

After her brother returned to the front line in France, Vera was anxious to continue serving as a VAD again. A few weeks after Edward had returned to battle (and against her parent’s wishes), Vera went to Devonshire House and asked to be assigned abroad. She explained to the clerk that she had left Malta because she was to marry a man who was blinded at Arras, but he died. (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 334). Vera was speaking of her friend Victor who she planned to propose to after Roland’s death. The clerk expressed sorrow for her recent suffering and asked Vera if she had a preference as to where she would like to go. Vera said, “I hated England, I confessed, and did so want to serve abroad again, where there was heaps to do and no time to think. I had an only brother on the Western Front; was it possible to go to France?” (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 334).

Vera arrived in France on August 3rd, 1917. She wasn’t feeling that well because she had a rough journey due to having a typhoid vaccination the previous day (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 334). Upon her arrival in Etaples, she let Edward know where she was located and he continued his correspondence regarding his combat experiences. Vera was ready to return to the hard labor of nursing. She explained that:

“I was as ready for sacrifices and hardships as I had ever been in the early idealistic days. This sense of renewed resolution went with me as I stepped from the shadowed quiet of the church into the wet, noisy streets of Boulogne. The dead might lie beneath their crosses on a hundred wind-swept hillsides, but for us the difficult business of continuing the War must go on in spite of their departure; the sirens would still sound as the ships brought their drafts to the harbor, and the wind would flap the pennons on the tall mast-heads.” (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 335).

It was also in France that Vera earned a scarlet efficiency stripe. This award was given to VADs who were “employed solely in military hospitals under War Office control, both in the United Kingdom and abroad” (Light, n.d.). She received this award while working in the wards of German soldiers during her time in France. It was alarming and uncomfortable for Vera to be working in this particular ward because she didn’t have any prior experience with German soldiers or civilians. She had “never been in Germany and had hardly met any Germans apart from the succession of German mistresses at St Monica’s, every one of whom I had hated with a provincial school girl’s pitiless distastes for foreigners.” (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 340). Propaganda had been rampant throughout the war, painting the Germans as violent, subhuman monsters. She inadvertently didn’t trust her German patients. She was concerned that the German patients would “get out of bed and try to rape [her]” (Brittain, 1994 ed, p.340). However, at the same time she knew that was not possible as her patients were severely injured and clinging to life.

The working conditions were not ideal. As Vera reflected upon her time in the ward at the hospital she wondered “how we were able to drink tea and eat cake in the theatre - as we did all day at frequent intervals - in that foetid [sic] stench, with the thermometer about 90 degrees in the shade, and the saturated dressings and yet more gruesome human remains heaped upon the floor” (Brittain, 1994 ed, p.341). She worked in unhealthy and challenging conditions. She described the conditions by stating, “the German ward might justly have been described as a regular baptism of blood and pus” (Brittain, 1994 ed, p.341).

The war was taking a personal and physical toll on Vera. She was constantly worried about Edward. She kept correspondence with Edward, but the few letters that she received were not much for consolation. She knew the gruesome details of war through the wounds she was dressing and the men that were dying before her eyes. Winter was approaching and it seemed as though the frigid temperatures and the desolation of war were certainly taking their toll on her.

After a grueling time in France, Vera’s father wrote asking her to come home because her mother had been put into a nursing home due to a diagnosis of a toxic heart. She was suspicious of the letter and wondered if it had been exaggerated knowing that her father had ulterior motives to encourage her to come home and be more feminine. She debated on whether she should leave to attend her mother or finish out her duty in France. She did, after much thought and discussion with Edward, decide to leave France (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 385-389). When she returned home, she found that her mother was in a deteriorating mental state (due to worry about her children) which had affected her physical condition. Vera was able to bring her mother home and care for her while simultaneously taking over her matriarchal household responsibilities. Vera stayed up to date with war time news even though she was no longer an active participant. A few short weeks after her departure she learned that the hospital where she had been in Etaples, France had been bombed, causing major chaos and a tremendous amount of casualties (Brittain, 1994 ed., p. 394). Not long after that, her brother Edward was killed on June 15, 1918. The war ended on November 11, 1918 with the Allied forces successfully forcing back the Germans. With the end of the war came a lot of reflection for Vera. She could not understand why the war couldn’t have ended before June to have saved Edward. She believed that the two sides could have ended it amicably. She felt that this would have brought an end to the war two years earlier rather than destroying her entire generation who had fought in it (Brittain, 1994 ed., p. 421).

Personal Life During WWI

In June of 1913, Vera was introduced to two of Edward’s good friends: Roland Leighton and Victor Richardson. All three boys attended Uppingham School and came home with Edward during a break. This was the first time that Vera met Roland Leighton, to whom she would eventually become engaged. Vera become very fond of Roland at their first meeting. In her journal entry dated June 29, 1913, she said “I like him immensely, he seems so clever & amusing & hardly shy at all” (Brittain, 1982 ed, p.38).

Their relationship progressed as friendship and they eventually fell in love. When war broke out in 1914, Roland joined the army. He was supposed to attend Merton College, Oxford while Vera was at Sommerville, but he was never able to attend. He began his service in France and wrote to Vera often. Vera shared her long night shift experiences with him while he would tell her of his time abroad and write her poems.

Roland was able to come home on leave in August of 1915. It was during his leave that he proposed to Vera. Vera hesitated to say yes at first because she was worried that she would hinder his future career. In her diary, Vera said that she “would never marry any man until [she] could prevent [herself] from being a financial burden to him” (Brittain, 1982 ed, p.237) and wondered if she would “hinder [his] brilliant career - or stand in his light in anyway” (Brittain, 1982 ed, p.237). She agreed to marry him the next day, but was only able to spend a few days with him before he had to return to his post.

While Vera and Roland were separated, they continued to write to one another about their experiences and their upcoming nuptials. This came to a heart wrenching end when unbeknownst to Vera, Roland was shot by a sniper while examining a wire. He died on December 23, 1915 just before his leave began for Christmas. On December 27, 1915, Vera received word that her beloved Roland had passed away. For the next week in her journal Vera only says that she worked her night rounds at the hospital and that she was desperately lonely and extremely miserable (Brittain, 1982 ed, p. 296).

After Roland’s death Vera was devastated. She had no interest in anyone or anything. She was so distraught that in her journal entries she admitted that she knew what a miserable person she was for everyone to be around (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 220). Because of the loss they shared in Roland’s death, and in their grief, Vera and Edward became even more close. By the time Edward had been sent to the front, Vera was almost unbearable for her coworkers to be around. At one point, one of the charge matrons had begun to chastise Vera for taking too long scrubbing and not being interested in her work. Vera tearfully responded that she wasn’t interested in anything and that her fiancé had just been killed and now her brother was being sent to the front line (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 229). When Edward had sent word that he was expecting to go into combat (using their code word “celery” in a letter) Vera was almost beside herself with worry (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 246). Edward was wounded in the battle and earned the coveted Military Cross award for his bravery, of which Vera was fiercely proud (Brittain, 1994 ed, p. 258). It was not the last time Edward would be wounded or that Vera would have the opportunity to care for her brother. The two maintained regular correspondence throughout the war until Edward’s death. After the devastation of Edward’s death on June 15th of 1918, Vera said she had no one whom she could spontaneously talk to and confide in until 1920 when she met Winifred Holtby (Brittain, 1994 ed., p. 406).

Vera’s outlook on life transformed after losing so many people that she loved, cared for and had grown up with. Her daughter said that after the war, Vera could no longer see the lightness of life; she had always been a serious-minded person but she wasn’t able to stay positive through a heavy situation. Vera was never the same after losing Roland and having to care for the wounded German soldiers that were in her charge, trying to keep them alive while her brother, fiancé and friends were risking their lives to do the opposite (Wigg, 2015).

Outside of work and corresponding with Roland, Vera’s personal life consisted of occasional short trips home and a few inconsequential daily routines such as writing in her diary and roaming London as a single young woman. She never mentioned any substantial hobbies or habits during that time.

Later Life, Pacifism, and Activism

With the end of the WWI and the devastation of losing her fiancé, brother, and several close friends in various battles, Vera realized the absurd nature of war. In Vera's first book, Testament of Youth, she describes the juxtaposition of her role in the war as opposed to her brother and fiancé. They were taking people's lives and she was working to do everything in her power to save the lives of soldiers (Mumford, 2009). Her war time trials were what spurred her movement towards pacifism. In 1918, she became a regular speaker for the League of Nations. She hoped for a peaceful future and believed for a time that peace was the best policy unless force was absolutely necessary.

Upon returning to Somerville, Vera met and became good friends with Winifred Holtby. The two became very close and shared the same political views having had similar wartime experiences. They graduated together in 1921 and shared an apartment together until 1925 when Vera married. Vera often referred to Winifred as her second self. Winifred even helped to raise Vera’s children upon the families move back to England from the United States. The two remained close and propelled each other’s ideals until Winifred’s death in 1935 (Simkin, 2014).

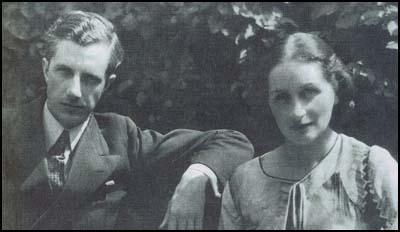

In 1925, she married George Edward Catlin, a political scientist and philosopher from Liverpool, England and the newlyweds moved to London where she encountered many other activists who helped to strengthen her belief in pacifism. Their daughter, Shirley Williams, described the difference between Vera’s two major love interests by saying Roland was her first love and that what George and Vera had was a mature love (Wigg, 2015). Williams shares that no one adored Vera more than George. As much as Catlin loved Vera, one of the hardest parts of their marriage and life together was moving past Vera’s first love and fiancé, Roland. Catlin once relayed to [Shirley] that the hardest rival you can have is a ghost (Wigg, 2015). After marrying George, the couple moved to the United States where George had gotten a job at Cornell University teaching political science (Simkin, 2014). The family moved back to England in the early 1930’s to continue raising their children.

Vera’s pacifist ideas underwent a metamorphosis in 1936. While attending a peace rally, she realized that her “study of peace had been too superficial; to delegate responsibility to a set of fallible politicians at Geneva was to over-simplify the problem of human violence and repudiate personal guilt” (Stec, 2001, p.239). This is where she became a true pacifist and concluded that “war was always wrong and should never be resorted to, whatever the consequences of abstaining from fighting” (Stec, 2001, p.239). As Vera became increasingly disturbed by the lack of effectiveness of the League of Nations, she pledged herself to the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship and the Peace Pledge Union (Bostridge, 2010). Despite Vera and her fellow activist’s efforts, WWII still came. They remained politically active throughout this time and continued to preach their message of peace.

Although Vera’s writing and political efforts did not stop the war, Vera never lost sight of her goal to have peace and to curb hatred. The Peace Pledge Union opposed bombing Germany as it was the women and children that were being killed. In 1942, Vera Brittain was on the Bombing Restriction committee and wrote for several publications regarding her pacifist views including Peace News. She also created “Letters to Peace-Lovers”, which she would send out every two weeks. In these letters, she “[protested] against the Allies’ policy of the saturation bombing of German cities” (Miller, n.d.). In 1944, she published her book, “Seeds of Chaos” which also criticized the bombing of Germany by Britain and America.

Vera was not one to just speak about peace, she did everything she could to practice it. She protested Germany’s treatment of Jews, helped with the food relief efforts by the Peace Pledge Union, aided refugees flee to Britain, and helped those people who lost their homes to the bombings (Peace Pledge Union, n.d.).

During WWII, Vera’s pacifism made the British government leery of her and her message. Because of her desire for peace at all costs, she was harassed and discriminated against by British citizens and authorities (Stec, 2001, p. 240). She was criticized for her pacifistic views and was accused, of collaborating with Germany (Stec, 2001, p. 240).

While London was bombarded by the Blitz in the Second World War, Vera and George decided to send their children to America to stay with friends in Minnesota for safety. The hope that she and her husband would be able to visit was short lived. She was unable to visit her children in America because she was accused of being an “unapologetic propagandist” (Poetry Foundation, 2017). Because of her outspoken views on the war, “the English government would not allow her to leave” because they “feared she might speak out against the United States’ involvement of the war.” (Peterson & Stewart, 1990, 401). Vera did not let anyone or anything deter her cause.

After the second world war, Vera lived relatively quiet life but was still heavily involved in political movements. She wrote about social injustices and turned her focus from primarily keeping peace to then trying to promote tolerance, squelch hatred of any group of people, as well as maintaining her fight for women’s rights. Vera and her husband George, also were early advocates for the independence of India after meeting with Mahatma Gandhi in 1931. Gandhi was one of the people suspected of having one of the greatest influences on the political stands of George and Vera and they followed his teachings of peaceful protest (Catlin, 1948). After Gandhi’s assassination, she wrote One Voice and Search After Sunrise and continued to support the Indian cause (Encyclopedia, 2017).

As Vera aged she continued to be an activist. Her daughter, Shirley Williams, is quoted saying “... I still remember her in her seventies, determinedly sitting in a CND demonstration, and being gently removed by the police” (Williams, 1994, p. 285).

Death

Vera had a fall in 1966 and never really recovered (Peace Pledge Union, n.d). She passed away in London on March 29th, 1970.

Testament of Youth and Other Works

Although Vera wrote many books throughout her career, Testament of Youth was the most well received and most important. This book was a memoir of her time as a VAD nurse during WWI.

For years, she tried to fictionalize her wartime experience without success. She finally gave in and published a memoir of her wartime experience. Vera wanted to keep Testament of Youth historically relevant, but also keep her readers interested. Vera wrote, “I wanted to make my story as truthful as history, but as readable as fiction.” (Poetry Foundation, 2017). The hardships that Vera endured during WWI did not become public until this memoir was published. Vera never stopped loving Roland; this is what made Testament of Youth so important to her. For Vera, her purpose of writing her novel was to share her experiences during the war and “to recreate the character[s] of the lives she had lost” (Day, 2015).

Testament of Youth was Vera’s first successful book; after it was published, she became a full time writer and activist (Peace Pledge Union, n.d.). Vera used her literature as her platform for social activism. Testament of Youth has been described as, “A statement against war.” (Peace Pledge Union, n.d.). Through her own involvement, Vera dedicated her novel to future generations to read about her experiences: a legacy of pacifism to be passed on in her novel that speaks to humanity as it was relevant then and historically relevant now.

Vera’s memoir, Testament of Youth, has been published, republished, made into a five episode PBS production, and a film. Her daughter, Shirley Williams, discusses how this new film is bringing her mother’s novel to a new generation and showing them the reality and hardships of war (Wigg, 2015).

After the release of her book Testament of Youth, Vera continued to write. By the time Vera died, she had written 33 books and numerous poems, short stories, and articles. Nearly 30 years after her death, many of her letters and much of her research have also been made public.

Legacy

Vera Brittain had a diverse impact on culture and society. It began as a young woman when she told her parents she would rather be educated than continue to be primed for marriage. Leading up to WWI the remanence of the Victorian era still had a strong hold in society. The juxtaposition of the impoverished and the posh was still very apparent and each social class had a sense of decorum they held to (Shaffer, N.D.).Vera’s vehemence towards following the status quo would not have been well accepted at this point in history. Although this was minor infarction in the overall scheme of Vera’s life, it set the precedence that she would follow her entire life. During her time as a nurse she often expressed her shocking desire to be in a marriage where she was allowed to work so she wouldn’t be a burden on her husband (Poluchuck, N.D.). She never would accept the idea that she should go along with a moré because it was culturally popular and consistently challenged societal norms and she aspired to “promote thought… combat indifference, inspire activity and to know everything of something and something of everything” (Reide, 2010, p. 84).

Although Vera was not well known, she was beginning to challenge the way women around her viewed their own possibilities. In many of Vera’s writings her activism is teaming just below the surface in the way she complains about the lack of doctors and says that it is a shame that women were not encouraged to advance. She also wrote about Serbian and French female doctors offering to help the British medical corps but were told “the only thing we expect from women is to go home and keep quiet.” (Brittain, 1994, p.171). This was just the beginning. Vera’s voice hadn’t reached out to very many people yet but her message was forming.

The importance of her book and activism is what she gave to society. She began using her writing as a podium, writing articles such as “Can Women of the World Stop War?” (Peace Pledge Union, N.D.). Her message to humanity was strong but simple, we are all people and we need to learn to get along. Her message to woman was even stronger. Vera believed there was no limit to what women can accomplish and that they should have every opportunity afforded to men. Women owe a lot to people like Vera who spent large portions of their lives fighting for equality and proving why it works and is important.

One of Vera’s lasting legacies is the contribution that she made to her children. Vera was a wife and a strong mother of two. While her children, Shirley and John, were young she would share stories of her time serving in Etaples, France and caring for wounded German soldiers that came into her care (Day, 2015). Her daughter Shirley, also known as the Baroness Williams of Crosby is one of the co-founders of the social democratic party in the 1980’s in the English Parliament and is continuing the legacy of her mother still today. She learned from her mother early on the principles of feminism and equal rights and has fought for them since a young age, encouraged by Vera every step of the way (Shirley, n.d.).

Selected Works

- The Dark Tide - First published 1923

- Testament of Youth - First published 1933

- Testament of Friendship - First published 1940

- England’s Hour: an Autobiography - First published 1941

- Seeds of Chaos (Massacre by Bombing in the US) - First published 1944

- Account Rendered - First published 1945

- Born 1925: a Novel of Youth - First published 1948

- Testament of Experience - First published 1957

- Women at Oxford - First published 1960

- Chronicle of Youth: The War Diary, 1913-1917 - First published 1981

- Letters from a Lost Generation - First published 1988

References

- Adie, K. (Ed.). (2014, April 2). World War One: The many battles faced by WW1's nurses. BBC News.

- Acton, C. (2014, October 8). Brittain, Vera. Retrieved from 1914-1918 Online: https://encyclopedia.1914-1918-online.net/article/brittain_vera.

- Bennett, Y. (1987) Vera Brittain: Feminism, Pacifism, and Problem of Class, 1900-1953. Atlantis, 12(2), 18-23. Retrieved from http://journals.msvu.ca/index.php/atlantis/article/view/4366/3606.

- Bostridge, M. (2010, January 22). Vera Brittain Biography. Retrieved from Biography Online: http://www.biographyonline.net/poets/vera-brittain.html.

- British Red Cross. (n.d.). British Red Cross. Retrieved from British Red Cross: http://www.redcross.org.uk/About-us/Who-we-are/History-and-origin/First-World-War/Volunteers-during-WW1.

- Brittain, Vera (1893–1970). Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Retrieved June 29, 2017 from Encyclopedia.com: http://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/brittain-vera-1893-1970.

- Brittain, V. (1982). Chronicle of Youth: The War Diary 1913-1917. A. Bishop et al. (Ed.). New York: William Morrow and Company, Inc.

- Brittain, V. (1981). Chronicle of Youth. Great Britain: Victor Gollancz Ltd.

- Brittain, V. (1980). Testament of Youth. Wideview Books.

- Brittain, V. (1981). Testament of Youth. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- Brittain, V. (1994). Testament of Youth: An autobiographical study of the years 1900-1925. New York, N.Y., U.S.A: Penguin Books.

- Catlin, George E. G. (George Edward Gordon) (1948). In the path of Mahatma Gandhi. Macdonald, London.

- Claudel, C. (2015, September 1). Vera Brittain in Malta. Retrieved from Lee A. Jacobus: http://www.leejacobus.com/blog/2015/9/1/vera-brittain-in-malta.

- Challenging Untruths. (n.d.) Retrieved from http://www.ppu.org.uk/bombing/bombing11a.html.

- Darmanin, D. A. (2010, May 4). A Forgotten Memorial. Retrieved from TimesofMalta.com: https://www.timesofmalta.com/articles/view/20100504/books/a-forgotten-memorial.305806.

- Davies, R. (2014). Testament of Youth: An autobiographical study of the years 1900-1925. By Vera Brittain. Nursing Education Today, 34(10), 1275-1276. Retrieved from http://www.sciencedirect.com.ezproxy.uvu.edu/science/article/pii/S0260691714001129.

- Day, E. (2015, January 11). Testament of Youth: The Observer. Retrieved from The Guardian: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2015/jan/11/shirley-williams-vera-brittain-testament-of-youth.

- Goldman, L. (n.d). Vera Brittain and Oxford Extension. Retrieved from https://www.conted.ox.ac.uk/about/vera-brittain-and-oxford-extension.

- Gorham, D. (1996). Vera Brittain: A Feminist Life. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Jones, S. (n.d.). Simon Jones Historian. Retrieved July 2017, from Simon Jones Historian: https://simonjoneshistorian.com/2015/01/08/where-did-vera-brittain-serve-in-france-during-the-first-world-war/.

- Light, S. (n.d.). The VAD. Retrieved August 4, 2017, from The Fairest Force: http://www.fairestforce.co.uk/5.html.

- Miller, A. (n.d.). The Vera Brittain Collection. (M. Bostridge, Ed.). Retrieved from http://www.oucs.ox.ac.uk/ww1lit/collections/brittain.

- Mumford, J. (2009, June 9). Vera Brittain From Women in European History. Retrieved July 5, 2017, from http://womenineuropeanhistory.org/index.php?title=Vera_Brittain.

- Peterson, B. & Stewart, A. (1990, Sept). Using Personal and Fictional Documents to Assess Psychosocial Development: A Case Study of Vera Brittain’s Generativity. Psychology and Aging, 5(3), 400-411. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.uvu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=pdh&AN=1991-00796-001&site=eds-live.

- Pettinger, T. (2010, January 22). Biography of Vera Brittain. Retrieved from http://www.biographyonline.net/poets/vera-brittain.html.

- Poetry Foundation. (2017). Poetry Foundation. Retrieved from https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/vera-mary-brittain.

- Poluchuck, H. (N.D.). Nursing, Feminism, and Pacifism in Vera Brittain’s Testament of Youth | . Retrieved from Literature of the Great War: New approaches: https://literatureofthegreatwar.wordpress.com/nursing-feminism-and-pacifism-in-vera-brittains-testament-of-youth/.

- Reide, A. (2010). Vera Brittain's Testaments of Labour, Work, and Action. Iowa Journal of Cultural Studies, 79-96.

- Shaffer, S. (N.D.). The Victorian Period. Retrieved from https://www.ucm.es/data/cont/docs/119-2014-02-19-3.%20The%20Victorian%20Age.pdf.

- Shirley Vivien Teresa Brittain Williams. (n.d.). Retrieved August 7th, 2017, from http://biography.yourdictionary.com/shirley-vivien-teresa-brittain-williams.

- Simkin, J. (2015, January). Vera Brittain. Retrieved from http://spartacus-educational.com/Jbrittain.htm.

- Simkin, J. (2014, August). Winifred Holtby. Retrieved August 2017, from Spartacus Educational: http://spartacus-educational.com/Jholtby.htm.

- Spongberg, M., Curthoys, A., & Caine, B. (Eds.). (2005). Companion to Women’s Historical Writing. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Stec, L. (2001, June). Pacifism, Vera Brittain, and India. Peace Review, 13(2), 237-244. Retrieved from http://ezproxy.uvu.edu/login?url=http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&db=aph&AN=4781190&site=eds-live.

- Vera Brittain: A Short Biography. Peace Pledge Union (n.d). Learn Peace: A Peace Pledge Union Project Retrieved from http://www.ppu.org.uk/learn/infodocs/people/pst_vera.html.

- Vera Brittain (n.d.). Somerville College. Vera Brittain. Retrieved from Somerville College: https://www.some.ox.ac.uk/about-somerville/somerville-stories/vera-brittain/.

- Williams, B. S. & Wigg, D (2015, January 9). Losing her first love haunted my mother all her life: Vera Brittain's fiancé, brother and friends were all killed at war, her daughter tells how the tragedy hit their whole family. Retrieved from Daily Mail: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/femail/article-2903445/Losing-love-haunted-mother-life-Vera-Brittain-s-fianc-brother-friends-killed-war-daughter-tells-tragedy-hit-family.html

- Williams, S. (1994). Preface. In V. Brittain, Testament of Youth (pp. 285-286). Penguin.

- WWI Centenary. (2017, July 20). Retrieved from University of Oxford: http://www.ox.ac.uk/world-war-1/people/vera-brittain