Sarah Emma Edmonds

Contributors

- Jennifer Bailey

- Gemille Eldredge

- Matthew Lynch

- Katelyn Van Ausdal, RN

Editors/Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

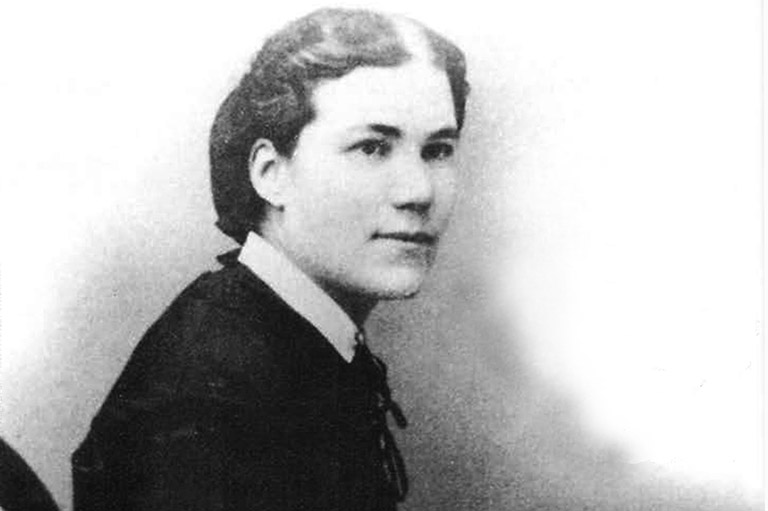

Sarah Emma Edmonds

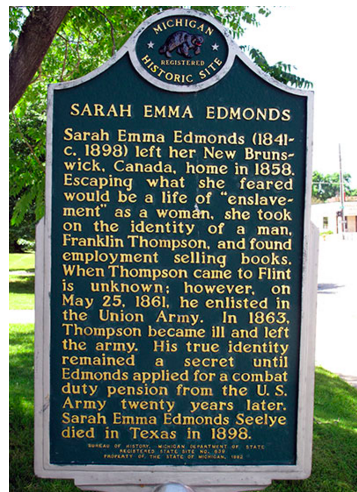

Sarah Emma Edmonds is a modern-day war hero, who was a soldier, spy, and nurse in the American Civil War. She learned early on in life, that in her time, men could do things and accomplish more than women. Because of this, she found that it was easier to do what she wanted and reach her goals if she disguised herself as a man. When she assumed a male identity, Sarah went by the name of Franklin Flint Thompson.

Early Life

Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmonson was born in December of 1841 in New Brunswick, Canada. She grew up with her sisters, and brother on their family farm near Magaguadavic Lake on the border of Maine. Sarah’s parents were from the United Kingdom, Ireland, and Scotland areas. They both immigrated to Canada in the early 1800s. Sarah’s father’s name was Isaac Edmonson. In the area where Isaac settled after immigrating, the population was thin, making finding hired hands nigh impossible. This meant that the only help he would get in future life would have to come from having sons. This being the case, it was almost natural that he would prefer male children, who would give him the help he needed on the farm and with other work duties. He married Elizabeth Leeper in New Brunswick, Canada, after she had also immigrated from the Ireland area. They started their farm and family pretty quickly. To Issac’s dismay, their first three children were girls. They were given the names Eliza, Frances, and Mary Jane. In 1832, they moved near Magaguadavic Lake, on a settlement now called Magundy, to start a new farm. They had another daughter that year named Rebecca Sarah, who is assumed to have passed away as a young infant.

Living in a farming environment, as soon as Isaac and Elizabeth’s daughters could, they started helping out and pulling their weight on the farm. The next child they had was a son named Thomas. It was the only boy they would have, but unfortunately, he had a health condition, which we now know as epilepsy (Zukauskas, 2017). This therefore meant that he was not able to help out on the farm, due to his seizures, leaving all the work to the girls. Her father resented the fact that he did not have any healthy, strong boys - and specifically that he did not get a boy when Sarah was born, her being the youngest child. Sarah was given the name, Sarah Emma Evelyn Edmonson, it’s thought that she was given the name “Sarah” in reference to her older sister, Rebecca Sarah, who is thought to have died before Sarah was born, keeping that part of her sister with her.

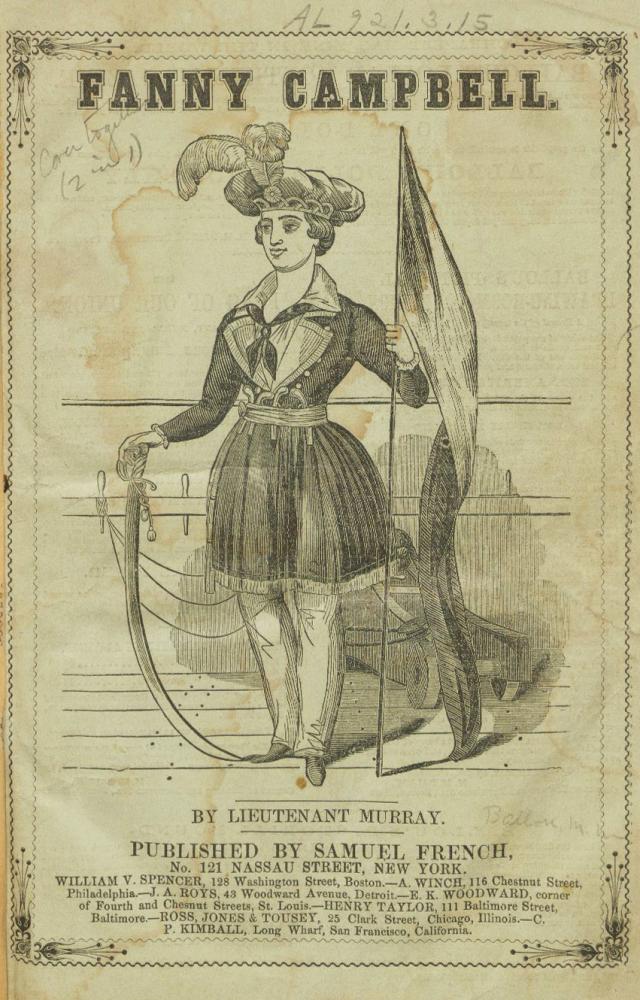

At age nine, Sarah was given a book by an old peddler. The book was about the adventures of “Fanny Campbell”, a teenage girl who disguised herself as a man and went sailing around the world to find and free her lover from a band of ruthless pirates. Fanny’s adventures inspired Sarah’s imagination, and in one of her memoirs she described herself by saying, “I am naturally fond of adventure, a little ambitious, and a good deal romantic- but patriotism was the true secret of my success.”

There was a one room schoolhouse near Sarah’s family home that she attended. It was there that she received a decent education. During certain farming seasons, she was unable to go to school. She would work on the farm from sun-up to sun-down, leaving little time for anything else, including school. Growing up in a rural settlement/town and helping to run the farm, Sarah gained many skills that would help her in her military service. She became an accomplished rider, a good shot with a rifle, and a strong swimmer by the time she was a teenager. She loved physical challenges. Some of her “adventures” included climbing tall trees and the mountains around the farm, when she was not needed at home.

Sarah’s father had a horrible temper and is said to have never treated her well. As previously mentioned, he had hoped that when Sarah was born, he was finally getting an able-bodied son. When he found out she was a girl upon her birth, he grew bitter. Becoming very angry and even abusive toward the women in the household at times. As a young child, to try and win her father’s favor, she would often pretend she was a boy, starting her charade of life as one, contemplating for years that it might just be better to run away. In 1857, at the age of sixteen, Sarah’s father had arranged a marriage for her to a much older man, who had similar abusive tendencies as her father. Because of this, and with the help of her mother, Sarah finally ran away from home.

Running Away

After her initial stint of running away from home, she went to live and work with a family friend in Salisbury. At this time, she changed her last name from Edmondson to Edmonds. She also dropped the first name “Sarah” and was known simply as “Emma.” She

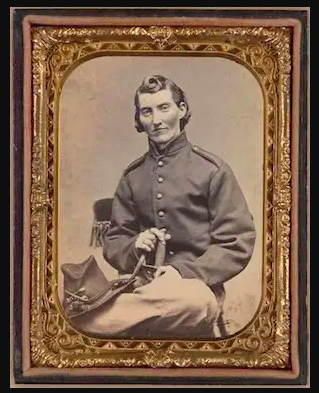

With her hair cut short and dressed as a man, she became twenty-one-year-old Franklin Thompson. Her first job as a man was as a traveling salesman, selling Bibles. While on her bible route, she made her way to Flint, Michigan where she settled in 1861. This was around the same time of year that the American Civil War started. At the start of the war, President Abraham Lincoln asked for seventy-five thousand volunteers to go and fight. Feeling that she should help however she could, she enlisted. In her own words, she “went to war with no other ambition than to nurse the sick and care for the wounded.” (womenhistoryblog.com) She also said, “I felt called to go and do what I could for the defense of the right; if I could not fight, I could take the place of someone who could, and thus add one more soldier to the ranks.” So she went and enlisted, hoping to help in any way that she could. The recruiting sergeant rated her as a field nurse.

Military Life

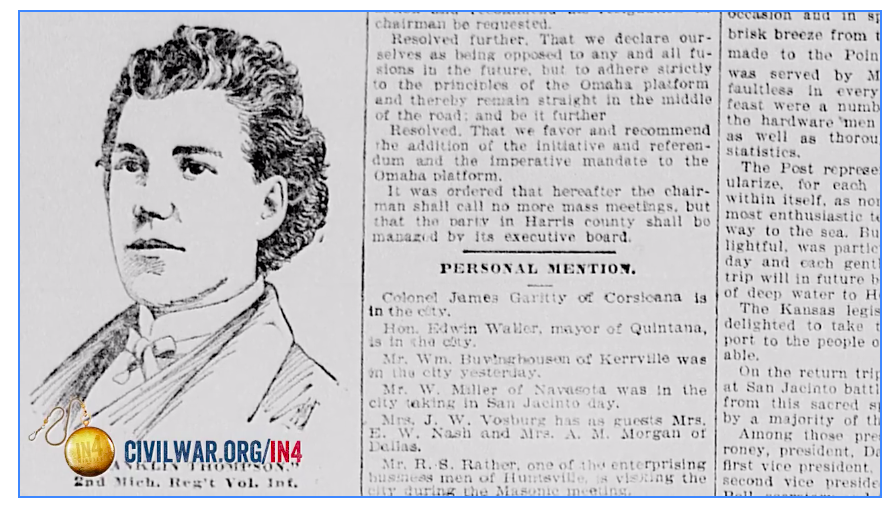

She was sworn in on the 25th of May under her alias, Frank, and served in Company F of the 2nd Michigan infantry for 2.5 years from 1861-1863.

Now, a very influential figure in nursing at this time was none other than Florence Nightingale. She made some major changes to nursing during the Crimean War, which started on October 5, 1853, and lasted until March 30, 1856. It was not until years after the war she would help influence and start nursing schools though. The late 1800s is when nursing schools started to come to the United States of America, which means in the timeline of things, that Sarah may have had a pretty decent education for the time, gained through normal means, but did not have an actual nursing education like we do today. There were no nursing schools for her to go to, meaning that all of her nursing experience would be learned on the job, and taught by simply methods of trial and error. At the time, there was also no department for nurses in the military, like the Army Nurse Corps, so they not only nursed the wounded, but she would have been expected to fight alongside her fellow soldiers as well.

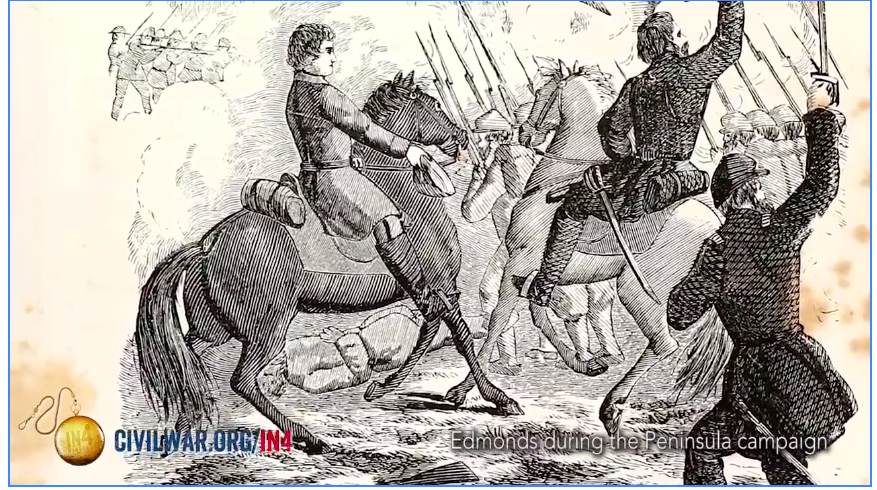

Edmonds fought in many battles including the Battle of Blackburn's Ford, the First Battle of Bull Run, and participating in the Peninsular Campaign from April–July 1862. She also took part in the Siege of Yorktown, being appointed as a Mail carrier when needed (American Battlefield Trust 2019). She also participated in Antietam, which was known as one of the bloodiest battles of the civil war (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica, 2017).

While Edmond’s company did not participate in the First Battle of Manassas, on July 21st, they played a big role whilst the Union was retreating from that battlefield. Edmonds herself stayed for hours after the battle, tending to the wounded and was nearly captured herself before escaping and returning to her unit up in Washington. (American Battlefield Trust, 2019) Her company was then assigned to fight the first big battle of the Civil War. “Though the Civil War began when Confederate troops shelled Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, the fighting didn’t begin in earnest until the Battle of Bull Run, fought in Virginia just miles from Washington DC, on July 21, 1861.” (Bull Run, 2020). This battle was a rush because the people at the time were trying to pressure President Lincoln into ending the war in just 90 days or less. Without much planning Lincoln ended up ordering Brigadier General Irvin McDowell, commander of the Union Army of Northeastern Virginia, to attack the Confederate forces commanded by Brigadier General P.G.T. Beauregard. General Beauregard’s army had a strong position at Bull Run Creek, just 2 miles northeast of the Manassas Junction. This location was key because it had a railroad track that connected the Shenandoah Valley with the Virginia interior. This gave them back up from yet another Confederate army under the command of General Joseph E. Johnston who was blocking the Union army route to the rebel capital at Richmond. McDowel planned to attack Beauregard’s army before Johnston’s army could reach them. McDowel’s plan would then open the road to Richmond and enable a march straight to the Confederate government.

The two armies met at Bull Run on July 17 where the fighting ensued. The battle was fairly evenly matched and had not been progressing much for either side. This caused McDowel to change tactics. He planned for 3 days figuring out how to attack next, but while he took those precious days planning, Johnston’s forces were able to march, unnoticed by the Federal's, to meet Beauregard army at Manassas.

“The morning of July 21 dawned with both commanders planning to outflank their opponent’s left flanks. McDowell’s early-morning advance up Bull Run creek to cross behind Beauregard’s left were hampered by an overly complicated plan that required complex synchronization. Constant delays on the march by the green officers and their troops, as well as effective scouting by the Confederates, gave McDowell’s movements away. Later that morning, McDowell’s artillery began by shelling the Confederates across Bull Run near a stone bridge. Two divisions under Colonels David Hunter and Samuel Heintzelman finally crossed at Sudley Ford and made their way south behind the Confederate left flank. Beauregard sent three brigades to handle what he thought was only a distraction, while planning his own flanking movement of the Union left.

Late in the afternoon, more Confederate reinforcements under Colonel Jubal Early extended the Confederate line and attacked the Union right flank on Chinn Ridge. Jackson’s men advanced across the top of Henry Hill and pushed back the Federal infantry, capturing some of the guns. The withdrawal of the Union center quickly spread to the flanks. At the battle’s climax Virginia cavalry under Colonel James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart arrived on the field and charged into a confused mass of Union regiments, sending them fleeing to the rear. The Federal retreat rapidly deteriorated as narrow bridges, overturned wagons and artillery fire added to the confusion. The calamitous retreat was further impeded by the hordes of fleeing civilian onlookers who had come down from Washington to enjoy the spectacle.” (Bull Run, 2020).

During the battle Sarah Edmonds was tending to the wounded when she was again almost captured by the Confederate cavalry while the Union Army was retreating. She wrote about her experiences at the First Battle of Bull Run saying:

“Our surgeons began to prepare for the coming battle, by appropriating several buildings and fitting them up for the wounded – among others the stone church at Centreville – a church which many a soldier will remember, as long as memory lasts. The first man I saw killed was a gunner. A shell had burst in the midst of the battery, killing one and wounding three men and two horses. Now the battle began to rage with terrible fury. Nothing could be heard save the thunder of artillery, the clash of steel, and the continuous roar of musketry.

I was sent off to Centreville, a distance of seven miles, for a fresh supply of brandy, lint, etc. When I returned, the field was literally strewn with wounded, dead, and dying. Men tossing their arms wildly calling for help; there they lie bleeding, torn and mangled; legs, arms and bodies are crushed and broken as if smitten by thunderbolts; the ground is crimson with blood.”

(https://www.womenhistoryblog.com/2008/09/sarah-emma-edmonds.html)When Confederate President Jefferson Davis arrived on the battlefield from Richmond, he spoke with Beauregard and Johnston. They decided even though they won the battle that their forces were too disorganized to continue in the attack to finish the Union army there. By July 22, what remained of the retreating Union army reached the safety of Washington DC. The Battle of Bull Run convinced the Lincoln administration and the North that the war would be a long and costly affair. McDowell was taken from command and replaced by Major General George B. McClellan. McClellan decided they needed to reorganize and better train what would become the Army of the Potomac. (Bull Run, 2020).

There were 60,680 soldiers who fought in the Battle of Bullrun; 28,450 Union led by McDowell and 32,230 Confederate led by Beauregard. There were an estimated total 4,878 casualties. The Union Army totals being; 460 killed, 1,124 wounded, and 1,312 missing/captured, accounting for 2,896 of the total casualties. The Confederate Army ended up with 387 killed, 1,582 wounded, and 13 missing/captured summing up the remaining 1,982 casualties. The Confederate army had about 4,000 more soldiers and about 1,000 less casualties allowing them to come out victorious.

Nursing Experience

Before this battle most nurses were simply volunteers. Due to the great losses seen, and many deaths after the Battle of Bullrun, a nursing corps was started by Clara Barton and Dorethea Dix. (Stein, 1999). Sarah could not be a part of the nursing corps since she was already enlisted as a male in the Union Army and would have been discovered as a female. Instead of joining the nursing corps after the battle she went on to work in a hospital in Alexandria, Virginia for a short time while, caring for the injured there. She then moved to a nursing post in Georgetown, Virginia at a different hospital. She not only cared for the soldiers' physical injuries but also for their mental trauma. She wrote in her journal describing her time there and this is what she wrote.

“Have been on duty all day. John C. is perfectly wild with delirium, and keeps shouting at the top of his voice some military command, or, when vivid recollections of the battle-field come to his mind, he enacts a pantomime of the terrible strife…” and “There are five hundred patients here who require constant attention, and not half enough nurses to take care of them.” (Young, 2016)

Hospitals were overrun with the wounded and sick. There would be as few as 60 nurses to care for over 1,400 patients. The female nurses were not received well by the doctors and surgeons at the time, and had a hard time completing their work. After some time had passed, the doctors started to warm up to them and learned to appreciate their efforts. Many of the nurses at this time were actually nuns. One of the nuns, Mother Angela, took it upon herself to improve the diet of the hospitalized which consisted of rancid pork and stale bread. She was able to replace it with rice, eggs, milk and chicken that she procured and prepared herself. (Stein, 1999).

Nurses would not only perform medical care, but they would also help prepare the men to return home. The nurses would use the connections they made with high up military personnel and doctors to secure food, money, and train tickets home for the soldiers once they were recovered enough (Stein, 1999).

Though far from a point of perfection, medical care during the civil war stared to really take shaped and become refined in hospitals as the need arose. One huge accomplishment was the establishment of an effective hospital system that treated the wounded and diseased through a series of continuously improving treatments and rehabilitation. In the decade before the war, American military action consisted of quick run-ins with Native Americans and the few that were wounded would seek treatment at random medical forts or small infirmaries. In bigger cities, hospitals were known as places that the poor or working-class people would go to, simply to die. It wasn’t until much later on that people viewed hospitals as places of healing.

“America’s hospital and medical system were not prepared for the devastation the new Minié ball bullet and the rifled cannon would inflict. The time-honored military tactic of lining up soldiers a few dozen yards apart to shoot at each other proved catastrophic. The massive casualties of the first battles brought old school medical thinking and preparedness into turmoil. At the first major land battle of the war on July 16, 1861 in Virginia at Manassas (Bull Run), two unproven green armies met and effectively slaughtered each other. The North suffered 2,700 casualties, the South 1,900. It was a Confederate victory. As there was no organized ambulance system to remove the wounded or an organized medical treatment system to treat the wounded, injured soldiers lay as long as three days on the battlefield. Local homes, churches and other structures were quickly turned into field hospitals. Hospitals routinely took both Union and Confederate wounded. In the larger battles of the war the casualties were staggering: Antietam 22,717; Shiloh 23,746; Spotsylvania 30,000; Chickamauga 36,624; Gettysburg 51,000.” (Burns, 2020)

An effective hospital and ambulance system was developed under the wonderful leadership of Union Surgeon General Alexander Hammond and his intelligent medical director and doctor Jonathan Letterman. It paved the way for the delivery of wounded military personnel through World War II. Instead of just getting general medical care, it tailored to specific needs such as outfitted mobile, field, brigade, specialty and rehabilitation hospitals. In towns where war wreaked havoc, buildings were turned into places to treat the sick and wounded. General Hammond hired some of the Nation's best doctors to visit these hospitals and perform inspections making sure that a higher standard of care was met. They also set the bar higher for sanitation guidelines in these institutions.

Almost three years into the civil war near the end of 1863, some of the bigger cities became the homes of new, well-ventilated, multiple-pavilion, style hospitals. Some of these hospitals had capacities up to 3,000 patients. Wounded soldiers were being transported much more quickly from the battlefield, major thanks to General Letterman’s new system with the ambulance corps. There were hundreds of tent hospitals now prepared to take on wounded soldiers near the battlefields, stabilizing soldiers before transport to actual hospitals. By war’s end, there were approximately 204 Union general hospitals with 136,894 beds. During the war, over one million soldiers received care in Union military hospitals, and likely a similar number in Confederate hospitals. (Burns, 2020)

Though war was still going, and nurses had their own opinions and sides of the battle, many times they would care for soldiers on both sides of the war. This would occasionally outrage the locals, who would then, sometimes threaten the lives of the nurses trying to kill the soldiers from the other army. On occasions when tensions were especially high after big battles, mobs would form and storm the hospitals. They would try and drag out the enemy soldiers, executing them no matter how defenseless they were. The nurses would do their best to protect all of their patients and would even hide them from the mobs when they could.

In May of 1862, during the Battle of Williamsburg, our dear “Franklin Thompson” got caught in the thick of things yet again. It was raining and she ran back and forth for hours on end, carrying stretchers laden with wounded soldiers. At one point she even helped with the fighting, grabbing a musket and helping to fire at the enemy with her comrades. (American Battle trust, 2019)

Dangers of War and Espionage

The summer following the Battle of Williamsburg, Edmonds kept up her appointed role as a mail carrier, which was dangerous work considering the challenges she faced on a daily basis. She would often carry messages over a distance of 100 miles through territory inhabited by people known as “bushwackers”. (American Battle Trust, 2019) They participated in a form of guerrilla warfare, attacking unsuspecting riders in areas of highly contested land with little to no governmental control. Bushwhackers swore no allegiance to either side of the war, instead preying on both sides for personal gain. After Edmonds’ time serving in the Peninsular Campaign ended, she finished her role as mail carrier, and returned back to Washington and her regiment who awaited her there.

On August 29, 1862 during the Battle of Second Manassas, Edmonds took on a new role. Headquarters had been impressed with her success as a nurse and also with her skill in horsemanship. Emma was known for being a daring and skilled rider and assumed the role of “messenger” when they were so badly needed. Because of these skills, she was selected to act as a courier for many of the Union generals. At this point in time, her horse had been recently killed in battle, so she was riding a mule. During one of her message runs, she was thrown off her mule and into a ditch, breaking her leg and sustaining some internal injuries as well. These injuries ended up plaguing her for the rest of her life. (American Battlefield trust, 2019) On December 13, 1862, she served as an aide to Colonel Orlando M. Poe in Fredericksburg. Her disguise as a man was so good, and her proven service to the Union very thorough, which led to her being allegedly asked to partake in intelligence missions.

Being selected to take part in reconnaissance missions, she essentially became a spy for the Union. During these missions she would mainly dress as a woman and gather information for the army. Experts believe she was one of a few hundred women who actually disguised themselves as men and fought in the war. It is thought that she fought with honor alongside some other disguised women. Some experts though, still debate the point of her becoming a spy as fact and not just fiction. Although skeptical, most would admit it’s very interesting that the dates she was “missing” from the Union Army match up with the dates of her alleged espionage missions she wrote about. In these writings she mentions how she played different personas including that of an Irish peddler woman, Bridget O’Shea, who sold apples and soap, a southern sympathizer named Charles Mayberry, an African American slave (thanks to the help of silver nitrate powder and a wig) called Cuff, and even a confederate soldier. (National Park Service, 2020)

Desertion of the Union

In the spring of 1863, the regiment was transferred to Vicksburg and under the direction of Army General Grant. Grant's men far outnumbered the defenders, so they tried a direct attack on the Rebels serving under General John Pemberton. To their surprise, the rebels were very skillful and beat off every attack, leaving the union with thousands of dead and injured soldiers. The weeks to follow wreaked havoc on both sides. During this nightmare, “Private Thompson” and the other nurses worked tirelessly taking care of the sick and wounded. They often worked days without rest and were left completely exhausted.

While serving in this manner, specifically with Edmond’s battalion fighting the Army of Cumberland, they were sent to Kentucky. (American Battlefield Trust, 2019) There she contracted what is now known as Malaria but was then known to the soldiers as “swamp fever”. She requested a furlough to go get medical care but was denied. She was fearful of being discovered as a woman if she sought help at a military hospital, so instead of going for treatment at an army medical facility, she opted

With this in mind, she realized she could not go back on active duty, so she then changed her name back to the name we know her as, Sarah Edmonds and lived as a woman. She wanted to continue serving the war effort even with her alias being essentially blacklisted by the Union. So, she “became” a nurse in the United States Christian Commission. She served in that capacity for the duration of the war. After spending so much time seeing suffering, she had become hardened and was quoted saying,

“Oh, what an amount of suffering I am called to witness every hour and every moment. There is no cessation, and yet it is strange that the sight of all this suffering and death does not affect me more… It does seem as if there is a sort of stoicism granted for such occasions.” (Young, 2016).

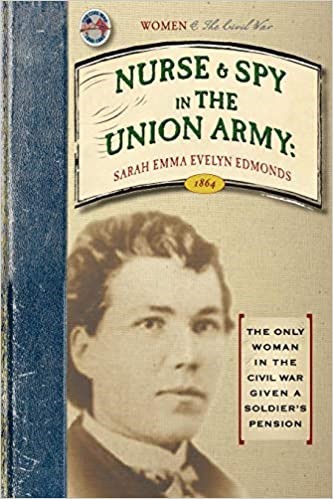

While serving in that capacity, she decided to write a book about her experiences as a nurse, soldier, and a spy during the duration of the war. She was then able to get published in 1864, dedicating the book, "To the sick and wounded soldiers of the Army of the Potomac." The original publishing became quite the success, the proceeds from it going mostly to charities such as the Sanitary Commission, the Christian Commission, and other soldier aid societies. (Ledoux, 2006)

Post War Life

After the war, she met and was married to Linus Henry Seely on April 27, 1867, in Cuyahoga, Ohio. Her husband, Linus being born on April 15, 1832, in St. Johns, New Brunswick, Canada. He worked as a mechanic, and Sarah had known him when they were children. After marrying, Linus and Sarah bounced around from Michigan to Illinois, Ohio, Louisiana, and Kansas, eventually settling in Fort Scott Kansas. (Wikipedia contributors, 2020) They had three children together, Linus B. Seely, Homer Seely, and Alice Louise Seely. Unfortunately, all three children ended up dying before the age of eight. Linus was born on April 14, 1869, in Charlevoix, Michigan and died a year later in 1870. Homer was born on June 21, 1871, in Evanston, Illinois and also died a year later on June 22, 1871, in Evanston, Illinois. Alice, their daughter, was born on April 11, 1873, in Oberlin, but she died seven and a half years later in Ohio on December 25, 1880.

Some sources claim that they adopted two children as well, the 1880 United States census shows a George and Charles lived with Sarah and Linus. So, it is thought that they adopted George Frederick Seely and Charles G. Seely. George being born on March 22, 1874 in Cleveland, Ohio, and Charles being born on May 1, 1873, in Oberlin, Ohio.

Route to Redemption

After settling in Fort Scott in 1882, Sarah began her quest to be recognized for her time as a soldier in the Civil War. The wounds she had suffered in consequence from being bucked off her mule plagued her often and stopped her from living her life. To this end, Edmonds attended a reunion of her military regiment, where she actively convinced her fellow soldiers that she was indeed Franklin Thompson, using her experiences and evidence of sustained war wounds as major selling points. After convincing them, she gathered several statements and affidavits from her comrades testifying of her role in the war and took those to the government. Simply asking that Frank Thompson’s desertion charges be removed considering the circumstances.

One of her former captain’s wrote on her behalf, saying,

“She followed that regiment through hard fought battles, never flinched from duty, and was never suspected of being else than what she seemed. The beardless boy was a universal favorite.”

She submitted these documents as evidence for her veteran’s pension. On July 14, 1862, Congress passed an act that started the General Law Pension System for Civil War Veterans. To get this pension you had to be a veteran who sustained war related disabilities. The pensions also became available to widows, children under 16 years of age, and dependent relatives of soldiers

The Grand Army of the Republic

Her recognition did not end there. In 1897, she was the only woman to be mustered into the Grand Army of The Republic as a regular member in Houston, Texas. The Grand Army of the Republic was founded by Benjamin Franklin Stephenson, M.D. and Chaplain Reverend William J. Rutledge. Dr. Stephenson was an army regimental surgeon. Both men had served in the Civil War in the 14th Illinois Volunteer Infantry and had actually been tent mates during Major General William Tecumseh Sherman's Expedition to Meridian, Mississippi in February 1864. They discussed founding an organization for soldiers during the expedition. The hope of the organization was that the ..." soldiers so closely allied in the fellowship of suffering, would, when mustered out of the service, naturally desire some form of association that would preserve the friendships and the memories of their common trials and dangers." In Decatur, Illinois on April 6, 1866, The Grand Army of the Republic was formed, due to their talking after the war and discussions during the war.

To become a member of the Grand Army of the Republic, a man must have served honorably in the United States Army, Navy, Marine Corps, or Revenue Cutter Service (today's United States Coast Guard) between April 1861 and December, 1865. He had to have been honorably discharged from the service and have never taken up arms against the United States. Membership was granted after the veteran applied to a local post and was approved for membership by being voted in. The reason she was the only woman mustered in is because women “did not serve” in the Civil War, even though it is thought that hundreds of women did disguise themselves as men and serve. She is the only one known to do this, and therefore the only one to receive this honor.

This is a huge achievement, not only because she was the only woman to have this honor, but also because of the time this happened. This was a time before women had a lot of say, or rights. Women were finally given their right to vote in 1920. Even after that point, women were still treated unfairly. In a time before this, when women were given very little privileges let alone be allowed to fight or help in war, Sarah was given the honor (even though she rightfully deserved it) to be in the Grand Army of the Republic. Also, to be given a pension for her service in the American Civil War.

Soon after she received that honor, she died at the age of 56 on September 5, 1898 in La Porte, Texas. It was believed that she died from a stroke. She was then buried in the Grand Army of the Republic section of Washington Cemetery in Houston, Texas. Years later in 1901, her remains were uncovered so they could bury her a second time, but with full military honors (The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. 2017). She continued to receive recognition for her time and service during the Civil War even after her death, and in 1992 she was inducted into the Michigan Women’s Hall of Fame.

References

- Bull Run. (2020, March 19). American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/articles/bull-run

- Burns, S. (2020) Behind the Lens: a History in Pictures. Civil War Era Hospitals. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/mercy-street/uncover-history/behind-lens/hospitals-civil-war/

- Derreck. (2017, March 14). Soldier Girl: The Emma Edmonds Story - Canada’s History. Canada’s History. https://www.canadashistory.ca/explore/women/soldier-girl-the-emma-edmonds-story

- Fiction, H. B. M. M. / &. (2014). Fanny Campbell, The Female Pirate Captain: A Tale of The Revolution. Read Online Free Books. https://bookfrom.net/maturin-murray-ballou/8720-fanny_campbell,_the_female_pirate_captain__a_tale_of_the_revolution.html

- Ledoux, Winifred . (2006). Winnie’s Website. Fred’s World. http://vermontcivilwar.org/winnie/tid033c.shtml

- Sarah Emma Edmonds. (2019, August 29). American Battlefield Trust. https://www.battlefields.org/learn/biographies/sarah-emma-edmonds

- Sarah Edmonds (U.S. National Park Service). (2020, October 4). National Park Service. https://www.nps.gov/people/sarah-edmonds.htm

- National Park Service. (2017, September 14). Sarah Emma Edmonds (U.S. National Park Service). https://www.nps.gov/people/sarah-emma-edmonds.htm

- Sarah Emma Edmonds. (2017, November 16). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4OTiRAylPek

- Sarah Emma Edmonds Gabbi H. (2016, May 20). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jj9hB24LNuU

- Shroyer. (2016, June 9). Uncommon Soldiers. Saint Mary’s College. https://www.stmarys-ca.edu/uncommon-soldiers

- Stein, A. P. (1999, September). Civil War Nurses. HistoryNet. https://www.historynet.com/civil-war-nurses

- The Editors of Encyclopedia Britannica. (2017, September 1). Sarah Edmonds | American Civil War soldier. Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Sarah-Edmonds

- Wikipedia contributors. (2020, June 23). Sarah Emma Edmonds. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sarah_Emma_Edmonds

- Young, P. E. (2016, August 17). Sarah Emma Edmonds: The Immigrant Woman “Male Nurse.” Long Island Wins. https://longislandwins.com/columns/immigrants-civil-war/sarah-emma-edmonds-the-immigrant-woman-male-nurse/

- Zukauskas, Rebecca. “Sarah Emma Edmonds.” Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia, 2017. EBSCOhost, search.ebscohost.com/login.aspxdirect=true&db=ers&AN=89405191&site=eds-live.