Virginia A Henderson

Contributors

- Katherine Cox

- Chase Dworshak

- Megan Kopp

- Bridget Mendelkow

Editors/Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University

The Early Years

Virginia Avenel Henderson was born on November 30, 1897 and lived over 98 years of service to her fellow man as she had a powerful career in public health. Virginia was born in Kansas City, Missouri being the fifth of eight children. She was a sister to; Lucy Ridgway Henderson, Charles Henderson, William Abbot Henderson, Jane Henderson, Frances Minor Henderson, Daniel Brosius Henderson II and John Overton Henderson (Norman, 2019). Her mother and father, Lucy Minor Abbot and Daniel Brosius Henderson, named her Virginia after her mother's native state, a state which she loved (Thomas, 1996).

Virginia Henderson was born into a family full of scholars for multiple generations. Her father Daniel was a former teacher at Bellevue and attorney who worked on the defense of the Native Americans against the United States government. One of his most creditable cases was the case of the Klamath tribe. With the importance of education being a family cornerstone, she first began her schooling at the age of 4 at Bellevue. She traveled to Virginia to live with her aunt and uncle, Charles Abbot, so she could receive an education (Gonzolo, 2019). It was taboo during these times for a girl to receive an education. Because of this, she attended the boy's preparatory school owned by her Grandfather, William Richardson Abbot, in Bellevue, Virginia. Although she attended school for many years, she did not get her diploma due to the fact she was a girl going to an all boys school. Not getting a diploma would also delay her nursing career (Halloran, 2018).

Nursing School

During World War One Henderson was moved by her two brothers serving in the army, and with the shortage of nurses, she dedicated her time volunteering and caring for wounded soldiers (Smith, 2015). It was here where she began to form an appreciation for nursing and considered her time there treating the soldiers to be a privilege. Shortly after, in 1918 Henderson was moved with American spirit to join the Army School of Nursing which was found in Washington D.C. The Army School of Nursing was created by the United States government on May 25, 1918. The school was created during World War I. The Secretary of War authorized the school to be open in order to utilize nurses aides in the army hospitals. The school was later shut down, there were a total of 937 young women nurses who received a diploma from the school. Among those who graduated were Mary G. Phillips and Rudy F. Bryant, who later became Chiefs of the Army Nurse Corps, and Virginia Henderson. Being accepted to the Army School of Nursing was one of her many accomplishments.

This was a difficult three year program. It included both classroom lectures and clinical experience in a hospital. The courses were taught at Teachers College, Columbia University. They attended classes for four hours each day and received five books to aid in their training. During the three year program they learned about many things including diseases and how to treat them. They learned about the different types of classes of diseases including cardiac, gastric, intestinal, nervous, infectious and contagious. They had courses on general surgery, orthopedics, and diseases of the eyes, ears, nose and throat. They learned how to perform bed-side nursing, dressing changes and treatments. For clinicals, a group of 25-50 students were assigned to a hospital. Upon arrival, students would move into their living quarters and take the nurses' oath of office. They worked for six to eight hours a day in the hospital. For the first four months they were required to wear an indoor uniform. The indoor uniform consisted of a blue gingham skirt, white collar and cuffs, an apron, the Army Nurse Corps cap and a plain black silk windsor tie. After four months they were required to get an outdoor uniform. The outdoor uniform consisted of a navy blue skirt, blouse, overcoat and hat. During training they were under strict military discipline (Jamme, 1918). It was during her time here that she questioned the strict control over the way they thought of patient care and the concept of nursing. Nurses were still seen as handmaids and were there to support the physicians. These thoughts and experiences would fuel her later in life for her writings and teachings (Smith, 2015). Even though she was treated like a cadet, she thrived in her studies at the Teachers College, Columbia University under the teachings of her mentor, Miss Anne Goodrich. Virginia graduated from the Army School of Nursing at Walter Reed Hospital in the year 1921.

The Beginning Work in Nursing

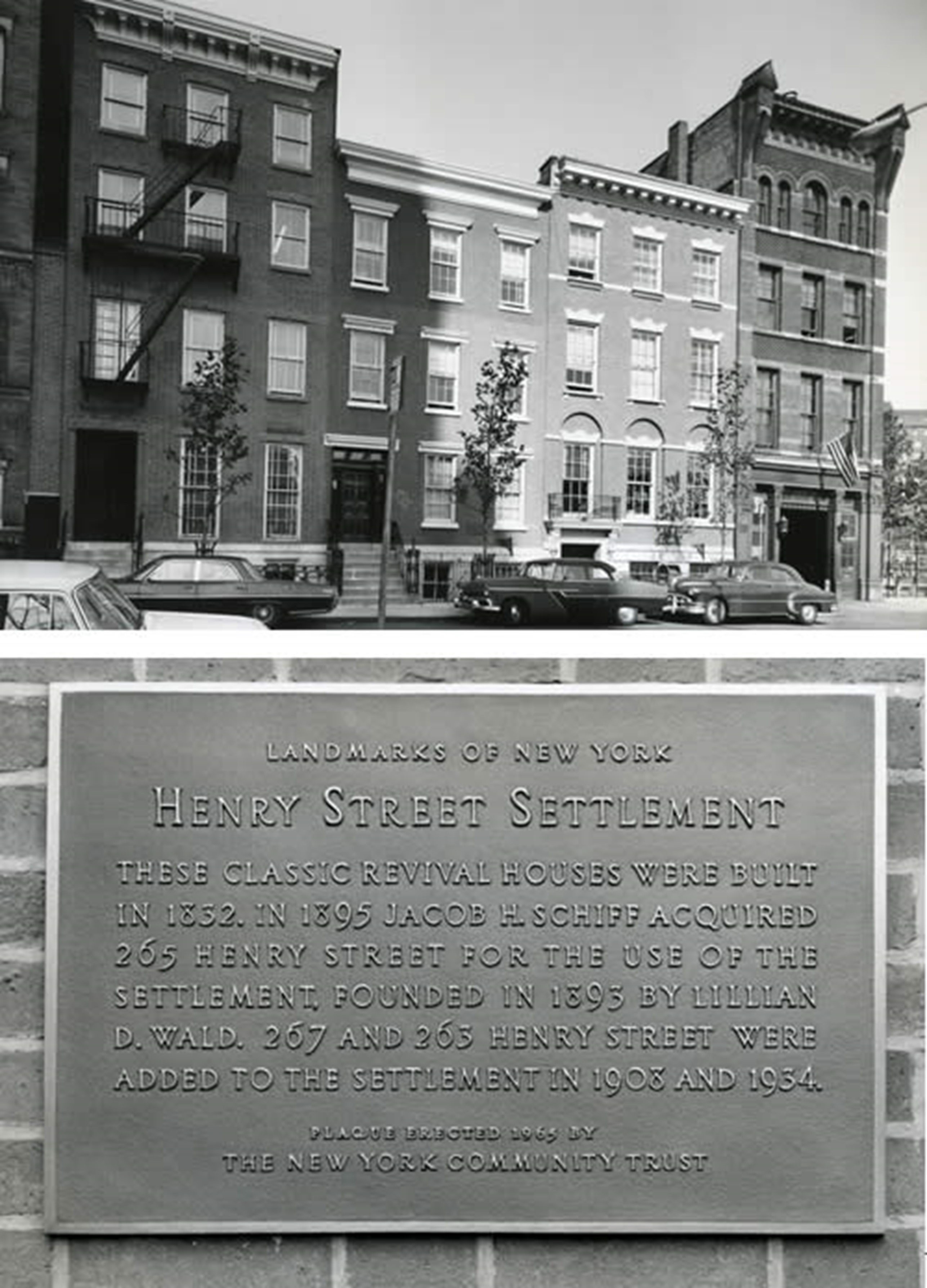

Henderson immediately began practicing at Henry Street Settlement in New York City. The Henry Street Settlement was settled in the lower East side of town to care for the poor. The founder of Henry Street Settlement was 26-year-old nurse, named Lillian Wald. Lillian moved to New York in 1889 to study nursing, which was only one of the few careers opened to women at that time. She worked on Henry Street for more than thirty years. Lillian Wald identified "four branches of usefulness" where she could be of service. Those four branches, "visiting nursing, social work, country work and civic work," helped guide the Settlement's programming, and turned Wald's home at 265 Henry Street into a center of progressive advocacy, and community support, that attracted neighbors from around the corner, and reformers from around the world (Levine, 2018). Later in 1902 The Henry Street Settlement opened a playground for the children to have a safe place to play, instead of in the streets. The Henry Street Settlement was the first place to pay a salary for a school nurse. All of the success of Lillian Wald has prompted the board of education to dedicate school nurses. In 1944 the Visiting Nurse Settlement separated from Henry Street Settlement to become the Visiting Nurse Service of New York. They focus on helping lower income families who cannot afford health care (Levine, 2018) Initially, Henderson planned on switching professions after 2 years. This plan changed during her summer work at this facility where she found a deep appreciation for the patient-nurse relationship. A relationship she really thought of to be a privilege. She was able to have less formal meetings and talks with her patients, as opposed to her experience at the Army School (Smith, 2015). Henderson enjoyed these informal meetings and found them to leave a greater impact.

After working for 2 years at the Henry Street Settlement, Henderson's passion for education grew and did not stop with just receiving her diploma in nursing from the Army School of Nursing. She felt driven to provide education to others. In 1924, she began a career in nursing education at Norfolk Protestant Hospital in her home state, Virginia. Norfolk Protestant Hospital is a large teaching hospital. In 1892 they started the first nursing school in Norfolk, Virginia (Sentara Norfolk General Hospital, 2020). Virginia Henderson was the first full-time nursing instructor in Virginia at that time. She served as an instructor there for five years. During her time teaching in Norfolk, she joined the Graduate Nurses Association of Virginia. She used this association to advocate for the need for psychiatric nursing in the current curriculum ("Virginia Avenel Henderson", 2020). Due to her advocacy, the Eastern State Hospital in Williamsburg, Virginia formed its first psychiatric nursing course in 1929. Following this she became a supervisor and clinical instructor in the outpatient department at Strong Memorial Hospital in Rochester, New York. The nursing program at Strong Memorial Hospital focused on integrating education, research and practice. Their program was unique at the time because they saw the importance of research. Research is key in developing knowledge and promoting evidence based practice. This was the start of Virginia's passion for research and writing (History of the School, n.d.). Later she was inspired to continue with her education by returning to Teachers College, Columbia University to receive her bachelor's and master's degree in nursing with the aid of a Rockefeller scholarship (Halloran, n.d.). She graduated with her bachelor's degree in 1932 and her master's degree in 1934.

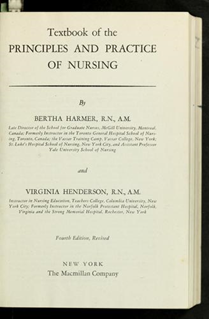

After earning her master's degree, Virginia Henderson started teaching at Teachers College, Columbia University. This college was founded in 1887. They are the oldest and largest graduate school of nursing in the United States. Henderson was the first professor in the school of nursing. She was an associate professor for 14 years (Gonzolo, 2019). Her outstanding teachings were talked about, and word spread. Soon she had students from many countries studying with her. During her time as a professor, Macmillan Publishing Company asked her to revise the fourth edition of the Textbook of the Principles and Practice of Nursing. This would be her first time working on this textbook, she later returned to contribute to several other editions of the book. There were several changes with medications such as antibiotics, new techniques for patients safety as well as their hygiene all the way to comfort care. Needless to say there were so many changes that the book needed to be revised. Henderson seemed to be the right fit to do this. Henderson felt like she needed to add her belief that the nurses job was actually to help the patient heal and be free of the need of help, as quickly as possible. This is where her "Need Theory" comes into the works. The "Need Theory" was based on the idea that a patient did not want to be sick, and helping the patient to heal, meet their own needs, and to come independent again, was the best care the nurse could give to their patient. The new textbook that was published in 1955, emphasized the nurse's responsibility to the patient, not the physician. (Gonzolo, 2019)

Nurses who were unable to travel devoured this book, it soon became a widely used and referenced book. 16 years later, in 1955, Henderson wrote the 5th edition of the same textbook. This edition focused on a new definition of nursing care. This new definition was �nurses assisted individuals, sick or well, in the performance of those activities contributing to health, its recovery (or to a peaceful death), that they would perform unaided if they had the requisite strength, will or knowledge�(Halloran, 1996). Henderson took on the challenge of defining the role of a nurse during a time when very few nurses had ventured into defining a modern nurse. This textbook helped shape the way we provide nursing care and was widely used in nursing schools throughout North America.

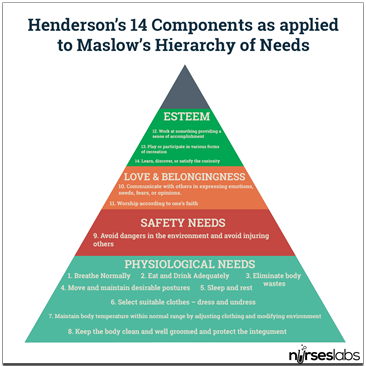

The Need Theory

This work in research Henderson did early on in her career is what later developed into her nursing "Need Theory". "The Need Theory" involves 14 concepts that include physiological, psychological, spiritual, and social components. Those concepts include breathing normally, eating and drinking adequately, eliminating body wastes, movement, sleep and rest, suitable clothes, maintaining body temperature, hygiene, avoid injury, expressing emotions or fears, worship according to your faith, have a sense of accomplishment, recreation and promoting normal development (Gonzalo, 2019). These seem like simple concepts, but Henderson identified them as essential parts of promoting a patients" well-being. She has been quoted saying, "The unique function of the nurse is to assist the individual, sick or well, in the performance of those activities' contribution to health or its recovery (or to a peaceful death) that he would perform unaided if he had the necessary strength, will, or knowledge" (Halloran, 1996). This needs to be done in such a way as to help the patient gain independence as rapidly as possible. The goal of the theory is to help the patients recover quickly and prepare them to take care of themselves outside of the hospital. This theory emphasized the nurses role in encouraging patients to do their own self-care. She always stressed the importance of a nurse's duty being focused on the patient. She felt that too often nurses spent time focusing on serving the doctor. By changing the emphasis on your patient care, she felt you can make better observations, aid in patient self-care and be a better tool for the hospital with the care provided. She really focused on the importance that nurses are to be there for their patient day and night. This theory is applied as a goal system for nursing practice. By meeting all 14 needs of the patients, nurses are better able to apply their overall nursing care and strengthen their skills. However, many nurses struggled to create a visual as to how they should be reaching all 14 components. Henderson's Nursing Need Theory is often connected back to Maslow's Hierarchy of Needs. By viewing the different components this way it is easier for nurses to better prioritize how they should be reaching all of the different components.

A way to look at her theory is that it is structured around four major concepts; individual, environmental, health and nursing. First, she focuses on the importance of looking at each patient individually and their specific needs. Look at the list of 14 components and see how your patient is meeting those components. What adjustments are needed to be made so all 14

In 1964, Henderson published a book called the Nature of Nursing. This book laid out the essential function of a nurse and how it applies to the nursing practice. The book acted as her platform for spreading the Need Theory throughout the nursing community. In this book she describes how a nurse'" role is �to get inside the patient's skin and supplement his strength, will or knowledge according to his needs."(Gonzalo, 2019). She talked about how her experiences as a nurse has led to her definition of a nurse and the Need Theory. When talking about her experience as a nurse in a hospital she said "I began to realize that the seemingly successful institutional regimen nevertheless often failed to change the factors in the patient's way of living that had hospitalized him in the first place" (Henderson, V, 1964). She saw the need for care that promoted the patients return to independence.

Research in Nursing

Her career in research started in 1953 when she joined the Yale School of Nursing as a research associate. It was a sweet reunion with her old mentor, Miss Anne Goodrich, who was currently the dean at Yale (McBride, 1996). This made her transition from Columbia to Yale even more exciting. During this time, Henderson began a 19-year project to evaluate nursing research and concluded there was insufficient research on nursing care. It was in these years of research that she worked on multiple research projects, helped write several pieces of literature such as The Basic Principles of Nursing Care, and made groundbreaking changes to the field of nursing. Throughout her career, Henderson was invited to many different universities from around the world to teach her new ideas and groundbreaking changes about nursing.

She went on to change the focus of research to the clinical aspect of nursing. In 1964, at the age of 67, Virginia Henderson and Leo Simmons published Nursing Research: Survey and Assessment. This 461 paged book was first reviewed by both graduates and professors of Yale. This survey was received well by the majority of the Yale faculty and student community. This publication was so inspiring it sparked a few of Virginia's fellow faculty members and students to start their own studies on the effects of nursing on patients (Halloran, 1996). This was her first, four volume, piece of literature that was made to organize nursing studies and papers. It would serve as an inspiration and foundation for the Nursing Studies Index she also published.

Nursing Studies Index

From 1959-1971 Virginia was funded to put together the Nursing Studies Index. At the time, clinical study literature was unorganized, therefore she took on the challenge to annotate it. She spent years collecting together studies, literature, and clinical works of nursing. "She gathered, reviewed, cataloged, classified, annotated, and cross-referenced every known piece of research on nursing published in English." (Gonzolo, 2019). This was the first time ever that a person had taken the time to organize and annotate nursing research. The first volume was published in 1963. In this volume, she spoke analytically of nursing from 1900-1959. One of her most famous lines from the first edition is, "We hope that those who used volume four of this index will send us criticisms of its form and content. Such comments will be considered in completing volumes three, two, and one...'"(Blackwell Science, 1996). She knew that there would be critiques of her writing, and she embraced that notion as she knew that would help with her future writings. She finished the final volume of Nursing Studies Index in 1972. With all four volumes put together, her Nursing Studies Index weighed in at an astounding 16.5 pounds (Halloran, 1996). The amount of work, research, and time that were needed to create the Nursing Studies Index is why many, including Hendersen herself, consider these books to be one of the most important contributions to nursing.

Registered nurses were some of the first non-physician organ transplant and donation specialists in the field. Henderson developed a nursing model based on activities of living. Henderson's principles and practice of nursing is a grand theory that can be applied to many types of nursing. Her theory is applied to intensely focused and specialized areas of organ donation for transplantation. Virginia Henderson's concepts are applied to the care and management of the organ donor, the donor's family and friends. (Nicely & DeLario, 2011). In some instances to the caregivers themselves. She has also gone as far as changing the attitude of the profession itself, and the purpose of it. Henderson's theory has had a tremendous influence on understanding nursing throughout the world. Many of the established models of nursing are based on her work.

The Basic Principles of Nursing Care

In 1960, The International Council of Nurses commissioned her to write an essay titled Basic Principles of Nursing Care. Having taken inspiration from helping rewrite the Harmer and Henderson Textbook on the Principles and Practice of Nursing, she was able to put together an essay that would be universal for all practices. This essay was able to be distributed worldwide for both nurses and patients. This was written "for the use of nurses who had neither access to technology nor the medical care required to establish disease diagnoses" (Halloran, 1996). Many people today compare it to a 20th century version of Florence Nightingale's Notes on Nursing. It is still being used throughout the world and in 29 different languages.

Her Final Years, Awards, and Recognitions

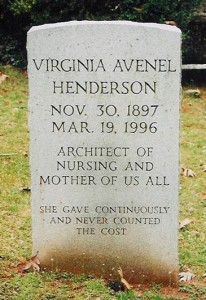

In 1971, Henderson changed her role at Yale from research associate to emeritus. She then continued to teach and travel but put her years of writing aside. Yale was founded in 1923, and was funded through the Rockefeller Foundation. Yale school of nursing was the first school within a university to provide nurses with an education, instead of an anticipation program. By 1934 Bachelor's degrees were required in order to get into Yale. By 1956 anyone entering the school into a graduate program needed to have a background in nursing ("Yale School of Nursing", n.d.). Virginia passed away on March 19, 1996, on her headstone you will find this engraved, "She gave continuously but never counted the cost." This was in fact exactly what she did. Upon her death, she was surrounded by friends and family as they ate chocolate cake and ice cream while saying their goodbyes at the Connecticut Hospice in Branford, Connecticut. (McBride, 1996). She was survived by her sister, Frances Houff, four nieces, a nephew, and several grand nieces and nephews (News, Y., 1996).

Throughout her career, Henderson received many awards and honors. "She received honorary doctorate degrees from the Catholic University of America, Pace University, University of Rochester, University of Western Ontario, Yale University, Rush University, Old Dominion University, Boston College, Thomas Jefferson University, Emory University and many others." (Gonzolo, 2019). In 1977 she was an honorary fellow of the American Academy of Nursing. In 1985 she was awarded the first Christiane Riemann Prize. This was the highest and most prestigious award in nursing. In 1988 she received the Virginia Nurse Leadership Award. In 1996 she was selected for the American Nurses Association Hall of Fame. In 2000, the Virginia Nurses Association recognized Henderson as one of fifty-one pioneer nurses in Virginia." A recipient of many awards, the Sigma Theta Tau International Library is named in Henderson's honor" (American Nurse Association). She made a powerful impact and was often called "The 20th century Florence Nightingale" and "Modern-Day Mother of Nursing". Henderson received numerous accolades and awards. In 2000 the Virginia Nurses Association recognized her as one of the 51 Pioneer Nurses in Virginia, and she is a member of the American Nurses Association (ANA) Hall of Fame (Dawn Magine, 2020).

References

- American Nurses Association."Virginia A. Henderson (1897-1996) 1996 Inductee" American Nurses Association. http://ojin.nursingworld.org/FunctionalMenuCategories/AboutANA/Honoring-Nurses/NationalAwardsProgram/HallofFame/19962000Inductees/virginiahenderson.html (Links to an external site.)

- Biography. (n.d.). Retrieved June 23, 2020, from http://vhenderson2011.blogspot.com/p/let-us-first-begin-by-saying-hi-to.html

- Congress, T. (2016, August 26). 1st Unit -- Army School of Nursing (LOC). Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/28956642110

- Dickinson, Jane . "Inspired by Virginia Henderson." Nursology. Jane Dickinson, 7 May 2019. Web. 3 June 2020.

- Gonzolo, Angelo "Virginia Henderson: Nursing Need Theory" Nurses Lab. August 24,2019 https://nurseslabs.com/virginia-hendersons-need-theory/

- Halloran, Edward "Virginia A. Henderson 1897-1996" American Association for the History of Nursing, https://www.aahn.org/henderson (Links to an external site.)

- Halloran, E. J. (1996). Virginia Henderson and her timeless writings*. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 23(1), 17-24. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.1996.tb03130.x

- Harmer, B. (n.d.). Textbook of the principles and practice of nursing. Retrieved July 01, 2020, from https://openlibrary.org/works/OL15828498W/Textbook_of_the_principles_and_practice_of_nursing

- Henderson's Nursing Need Theory. (n.d.). Retrieved August 12, 2020, from https://nursing-theory.org/theories-and-models/henderson-need-theory.php

- Henderson, V. (1964). The Nature of Nursing. The American Journal of Nursing, 64(8), 62-68. doi:10.2307/3419278

- History of the School: University of Rochester School of Nursing. (n.d.). Retrieved July 27, 2020, from https://www.son.rochester.edu/about/history.html

- Hoyle, M., Senior. (2019, June 07). Virginia Avenel Henderson: Foremost Nurse of the 20th Century. Retrieved July 12, 2020, from https://www.shiftwizard.com/virginia-avenel-henderson/

- Inductees Listed Alphabetically. (n.d.). Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/history/hall-of-fame/inductees-listed-alphabetically/

- Jamme, A. (1918). The Army School of Nursing. The American Journal of Nursing, 19(3), 179-184. doi:10.2307/3406200

- Levine , Lucie . (2018, November 30). Lillian Wald's Lower East Side: From the Visiting Nurse Service to the Henry Street Settlement. Retrieved from https://www.6sqft.com/lillian-walds-lower-east-side-from-the-visiting-nurse-service-to-the-henry-street-settlement/

- Lopes, J. (n.d.). Public Health Nursing. Retrieved August 10, 2020 from https://venngage.net/p/159776/public-health-nursing-by-jenna-lopes

- Mangine , D. (2020, March 11). Virginia Henderson: The first lady of nursing. . Retrieved from https://blog.simtalkblog.com/blog/virginia-henderson-the-first-lady-of-nursing

- McBride, A. B. (1996). Virginia Avenel Henderson, RN, MA. Retrieved July 12, 2020, from https://www.sigmarepository.org/vhenderson/

- Memorial for Nursing Pioneer Virginia Henderson. (2011, September 12). Retrieved May 26, 2020, from https://news.yale.edu/1996/04/30/memorial-nursing-pioneer-virginia-henderson

- (n.d.). Retrieved June 23, 2020, from http://currentnursing.com/nursing_theory/Henderson.html

- News, Y. (1996, April 30). Memorial for Nursing Pioneer Virginia Henderson. Retrieved July 12, 2020, from https://news.yale.edu/1996/04/30/memorial-nursing-pioneer-virginia-henderson

- Nicely, B., & DeLario, G. T. (2011). Virginia Henderson's Principles and Practice of Nursing Applied to Organ Donation after Brain Death. Progress in Transplantation, 21(1), 72�77. https://doi.org/10.1177/152692481102100110

- Norman, R. (2019, May 09). Virginia Avenel Henderson. Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Henderson-6552 (Links to an external site.)

- �Our History ." Henry Street Settlement , https://www.henrystreet.org/about/our-history/.

- "Our History ." Strong Memorial Hospital, https://www.urmc.rochester.edu/strong-memorial/about-us/history.aspx.

- "Remembering the First Lady of Nursing." Virginia Henderson Global Nursing e-Repository, www.nursinglibrary.org/vhl/pages/VHLonRNL.html. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

- Seletyn. "WOMEN'S HISTORY MONTH: VIRGINIA HENDERSON (NURSING)." Thoughts and Ponderances The Adventures Of Chelle. Thoughts and Ponderances The Adventures Of Chelle, 31 Mar. 2020. Web. 3 June 2020.

- Sentara Norfolk General Hospital. (2020, May 30). Retrieved July 29, 2020, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sentara_Norfolk_General_Hospital

- Smith, M. C. (2015). Section II; Conceptual Influences on the Evolution of Nursing Theory. In M. E. Parker (Ed.), Nursing Theories and Nursing Practice (Fourth Edition ed., p. 56). Philadelphia, PA: F.A Davis Company.

- Thomas, R. M., Jr. (1996, March 22). Virginia Henderson, 98, Teacher of Nurses, Dies. Retrieved June 10, 2020, from https://www.nytimes.com/1996/03/22/arts/virginia-henderson-98-teacher-of-nurses-dies.html (Links to an external site.)

- Vera, Matt. "Virginia Henderson's Nursing Need Theory." NursesLabs, 6 Aug. 2014, nurseslabs.com/virginia-hendersons-need-theory/. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

- "Virginia A. Henderson (1887-1996)." American Association for the History of Nursing, www.aahn.org/gravesites/henderson.html. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

- "Virginia A. Henderson (1897-1996) 1996 Inductee." ANA American Nurses Association , http://ojin.nursingworld.org/FunctionalMenuCategories/AboutANA/Honoring-Nurses/NationalAwardsProgram/HallofFame/19962000Inductees/virginiahenderson.html.

- "Virginia A. Henderson (1887-1996) 1996 Inductee." American Nurses Association, www.nursingworld.org/VirginiaAHenderson. Accessed 23 Feb. 2017.

- Virginia Avenel Henderson. (n.d.). Retrieved June 23, 2020, from https://gallery.library.vcu.edu/exhibits/show/vanursinghalloffame/item/77970

- "Virginia Avenel Henderson," VCU Libraries Gallery, accessed June 10, 2020, https://gallery.library.vcu.edu/items/show/77970

- "Virginia Henderson, Nursing Pioneer." Tampa Bay Times 15 Sept. 2005: n. pag. Print.

- Virginia Henderson's Need Theory http://currentnursing.com/nursing_theory/Henderson.html

- Wikipedia contributors. "Army School of Nursing." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 21 Oct. 2019. Web. 6 Aug. 2020.

- Wikipedia contributors. "Teachers College, Columbia University." Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia, 2 Aug. 2020. Web. 6 Aug. 2020.

- Yale School Of Nursing: History . (n.d.). Retrieved from https://nursing.yale.edu/about/history

- Yale University Library Online Exhibitions (n.d.). Yale School of Nursing: Better Health for All People. Retrieved July 01, 2020, from https://onlineexhibits.library.yale.edu/s/yale-nursing/page/new-focus-on-research