Anna Caroline Maxwell

Contributors

- Holly Dayley

- Scott Hall

- Skie Freymoth

Editors/Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University

The Introduction of Ms. Anna Caroline Maxwell

Anna Caroline was born on March 14, 1851 to John Eglinton Maxwell and Diantha Caroline Maxwell in Bristol, New York, and was the eldest of three and was of European descent. Her father, John, was born in Scotland, and came from an esteemed military family. He was educated at the University of Edinburgh and was an ordained clergyman. Anna's mother, was born on American soil and had a family tree of English descent. Records indicate that Anna’s ancestors, mainly that of Diantha's family, traveled to America in 1634, where they resided as they grew and built a family and a life.

Though being of military descent, Anna’s father was also a Baptist minister. Perhaps having military and religious themes in her household is what contributed to Anna’s assertive yet compassionate personality. Though we don’t know everything about Anna’s upbringing, we do know that her father made the decision to move his family to King, Ontario, Canada. While living in Canada, John and Diantha welcomed two more daughters into their family, making Anna the eldest of three children and one member of a family that was only 2/5th American.

During Anna’s young life, she was mostly taught by her well-educated father, as he was home much of the time. As Anna grew, her education continued with tutors who were hired to teach her at home. Records also indicate that Anna attended a Canadian boarding school for two years to further her education (A.N.A., 2018).

The Dawn of a Career

The starting point of Anna’s nursing legacy originated when Anna returned to the United States in 1874 at the age of 20. Shortly after her first homecoming to America she accepted a position at the New England Hospital where she received three months of obstetrical training and held the title of ‘Assistant Matron’ even though she had no formal nursing education, making this appointment even more commendable.

In 1878, Anna chose to further her education and pursue a degree in nursing at the Boston City Hospital Training School for Nurses. Anna received the honor of learning and training under Linda Richards, the first professionally trained American nurse and an esteemed woman who made great advancements in the nursing field. Her intelligence and commitment to teaching the up and coming nurses made her stand out, in addition to her vision of the nursing world and care of patients. The time layout for Linda's program was,

" The probation term was one month; the course two years; to weeks of holiday each year." (Maxwell, 1921)

Nurses were on the floors day and night and were witnesses to everything that was happening. Anna noted that at one time a physician asked if the head nurse doesn't know, than who would know. Anna's first head nurse was truly the kind who knew what was happening and had made a big impression on Anna and her developing career. Anna worked on many different wards and experienced different areas of patient care. She worked on a gynecological ward, a men's surgical ward, was a nurse to many who suffered from typhoid, as well as a wide range of different cases.

Two years following her enrollment in Boston’s nursing school, Anna graduated with her nursing degree and traveled back to Canada where she worked tirelessly for a period of time to improve conditions in the Montreal Hospital (A.N.A., 2018). Though Anna was both humble and hardworking, her efforts were not welcomed and the physicians at the hospital were not willing to work with her and implement improved standards of care.

Anna kept records of her experiences and the differences she battled during her service in different hospitals, as well as publishing articles and material to further benefit the upcoming generation of nurses. The work published Hospital and Training School Administration included great detail about the disastrous conditions in some of the hospitals she went to serve in. No elevators were in the hospital, and the nurses used a form of a stretcher that resembled more of a basket and three handles and patients who could not walk would be moved in said stretcher. Anna even made remarks of how she and the nurses had to be strong in order to transport a patient who was around one hundred and eighty pounds up three floors. Training and education in the hospitals were not first priority. Anna made it clear that the care of the patient and attending to chores took first priority. Class time and quizzes seemed to be few and far between.

Anna once again reentered the United States in late 1881. Boston City Hospital Training School for Nurses hired her, and she was able to make changes to the school’s curriculum which improved standard nursing care and would, in turn, result in the production of nurses who were better equipped to face the illnesses present in society.

Miss Maxwell was thought very highly of by her peers, and even her superior Dr. Rowe, both the resident physician and Superintendent of the hospital, stated fondly:

Miss Maxwell in my judgment possesses unusual qualifications for a nurse. She brought to her vocation an enthusiasm for her work, a good education, good physical health, an earnest desire to excel and quick observation. During her course she developed the ability to command and obey, great fertility of resources and the uses of economy, in time and material. She is an excellent instructor and rendered our Superintendent of Nurses very great aid. I esteem her admirably fitted for the position of Superintendent of a Training School, and should feel confident of her success (Lipincott, Williams & Wilkins, 1921).

This favorable message from Anna’s Superintendent, Dr. Rowes, expressed Anna’s strength as a nurse and proved to be a wonderful recommendation letter after she decided to take a break from teaching, and pursue a career in more patient-based care. The Training school Anna was teaching at had many connections to Massachusetts General Hospital where she applied. As the hiring team recognized her value, Anna was quickly hired on as Superintendent at Massachusetts General Hospital. Due to her ceaseless attention to detail, she was able to improve the standards of care that the hospital was providing to their patients. Much of the structuring of the training eventually found its way into other schools, such as Teachers College, which is now known as “Teachers College, Columbia University” and is the oldest and largest graduate school of education in the United States (Miller, 2017).

Anna Maxwell moved to New York in 1889 where she became the director of nursing at St. Luke’s Hospital; however, her stay at St. Luke’s was short-lived and a year later she transferred to Presbyterian Hospital of New York, where she resided until 1921. During her time at Presbyterian Hospital Anna became involved with the military and played a large part in the Spanish-American War. Anna was an incredibly ambitious and hard-working woman and before the age of 50 she had become a charter member of the American Society of Superintendents of Training Schools for Nurses, the forerunner of the National League for Nursing, the forerunner of the Nurses’ Associated Alumnae of the United States and Canada, the forerunner of the American Nurses Association, a charter member of the International Council of Nurses, and a charter for the American Red Cross Nursing Service which allowed her to play such an influential and prominent role in the oncoming War (A. N.A., 2018).

Spanish-American War (1898)

During the Spanish-American War the United States Surgeon General refused to have nurses be involved with military field hospitals, fearing that women nurses on the battlefront would seem out of place amongst men involved in combat. As the war persisted the US became engaged in a fight with an unforeseen enemy that would ultimately require the aid of nurses. That enemy was tropical disease, which eventually rendered the hospital corps inadequate to meet military needs (Miller, 2017).

As tropical disease started to ransack military camps Army officials eventually recognized the need to have an increase of medical personnel involved in camp to treat sick and ill soldiers. After seeing this desperate scenario, nurses were permitted to be hired and for the first time in United States history, there would be a unit of nurses - working under their own command - in military hospitals (Miller, 2017).

Maxwell was a significant driving force in the recruitment of nurses that would serve in the Spanish-American war. She persuaded nearly 200 graduate nurses to enlist. On top of helping graduate nurses enlist, she was a leader to many of them as they were assigned to Camp Thomas in Chickamauga Park, Georgia (Miller, 2017).

The conditions Anna and her team worked in to battle the typhoid epidemic were unforgiving and laced with other serious diseases such as malaria, and measles. Though the conditions were hardly ideal, Maxwell and her teams still managed able to help heal and improve the wellbeing of the soldiers under her care (Miller, 2017).

Maxwell and her team took care of approximately 900 soldiers, most of them suffering from typhoid fever and malaria. Out of the approximate 900 soldiers that they cared for, only 67 passed away. This resulted in over 92% of the soldier survival rate under the leadership and direction of Maxwell (Miller, 2017).

Motivated by such an accomplish, Maxwell and her cohorts returned home and began persuading congress to create The U.S. Army Nurse Corps and were successful in doing so. On February 2, 1901, the Nursing Corp became a permanent corps of the Medical Department. Nurses were now allowed to be appointed in the regular army, but they were never actually commissioned as officers (Miller, 2017).

Continuing Career

During the 30 years Anna Maxwell spent at Presbyterian Hospital, she organized the hospital’s nursing training school: a two-year program of clinical practice along with classroom instruction including an education in medical/surgical nursing as well as the study of obstetrics. Anna soon added the study of contagious disease to the curriculum; and, over the years, the program became a three-year nursing program for an associate degree in nursing (A.N.A, 2018). Along with her extensive educational work, Anna also co-authored a book entitled Practical Nursing: A Textbook for Nurses and a Handbook for All Who Care for the Sick (Hannik, 2018).

As time went on and World War I broke out, Anna once again volunteered her efforts to serve her country and those in need. During her service in the Great War, Anna was able to stay on with Presbyterian Hospital as chief of unit, and through her connection to the Red Cross she organized nurses for the unit that Presbyterian Hospital supplied to the war effort. Anna made trips to the facilities located at the military front, in Europe, to provide care to the wounded soldiers, and also helped train nurses who volunteered themselves for active military service (Hannick, 2018.).

For Anna’s exceptional work in the war, the French awarded her with the Medaille de l’Hygiene Publique, also known as the Medal of Honor for Public Health (Hannick, 2018).d After World War I ended, Anna returned her focus to Presbyterian Hospitals training nursing program, and by 1917, it was turned into a five-year bachelor of science degree from Columbia University with a nursing diploma from Presbyterian Hospital.

Social Life

Though Anna Maxwell never married or had children, she was recognized by many as the most nurturing of caregivers. One of Anna’s dearest friends wrote:

‘First and last and always, Mother, through her tender ministrations to the young and sick and helpless, that’s the woman as I see her not a dew-drop, not a plaything, for your poets or your princes, but a splendid great creation, from the Master-Builder’s workshop for the healing of the nation (Lipincott, Williams & Wilkins (1921).

Anna may never have had biological children, but she was a mother to many patients, friends, and soldiers due to her loving, caring nature.

Outside of the realm of nursing Anna had her own life. She belonged to two New York Clubs; first the Cosmopolitan, which was a private club organized exclusively for women interested in the arts, sciences, education, literature, and philanthropy. Anna was also a member to the Women’s City Club, which was also exclusively for women and engaged in political dialog, promoted civic engagement, activism and leadership. Members of both clubs have included the likes of Helen Hayes, Ellen Glasgow, Marian Anderson, and even First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt (James, James & Boyer, 1971).

Anna loved music, opera, and the theater. Many of Anna’s coworkers nicknamed her “The Queen” and had vivid memories of her dressed for a gala evening out in a long black gowns and a scarlet Spanish shawl. Tall, dignified, and carrying herself with a stern disciplinary ambiance, Anna was beautiful and contributed to the wellbeing and joy of many around her. With her deep brown eyes accompanying her charming characteristics and persona, Anna was also known for her magnificent vitality. She also had many social contacts which contributed to her success in the world of nursing (James, James & Boyer, 1971).

Maxwell retired from active nursing in 1921, but Columbia called her out of retirement to help make the nursing school's new home a reality. She ultimately raised half a million dollars for Anna C. Maxwell Hall, which opened in 1928 as the first building of the new medical center where generations of future nurses were educated (Miller, 2017).

Retirement and Death

Noted for her enthusiasm, Anna was also known for her dedication to her work as a nurse. It wasn't until Anna was 70 years of age that she finally resigned from her leadership role at the Presbyterian school. Even at the that age, many looked shocked at her decision, however Anna held her head high and looked forward to travel and time with friends and family. After so many years dedicated to her work and teaching it was time that she enjoyed these simple aspects of life. However, life had a different plan for her. Anna found herself as a patient in the Presbyterian Hospital in November of 1927 for the treatment of a cardiac conditions that never officially received a diagnosis. Four short months later in March of 1928, she became the first patient ever to be transferred to Harkness Pavilion Medical Center. Anna passed away in Harkness Pavilion just one short year later, in January 2, 1929. (Maxwell, 1921)

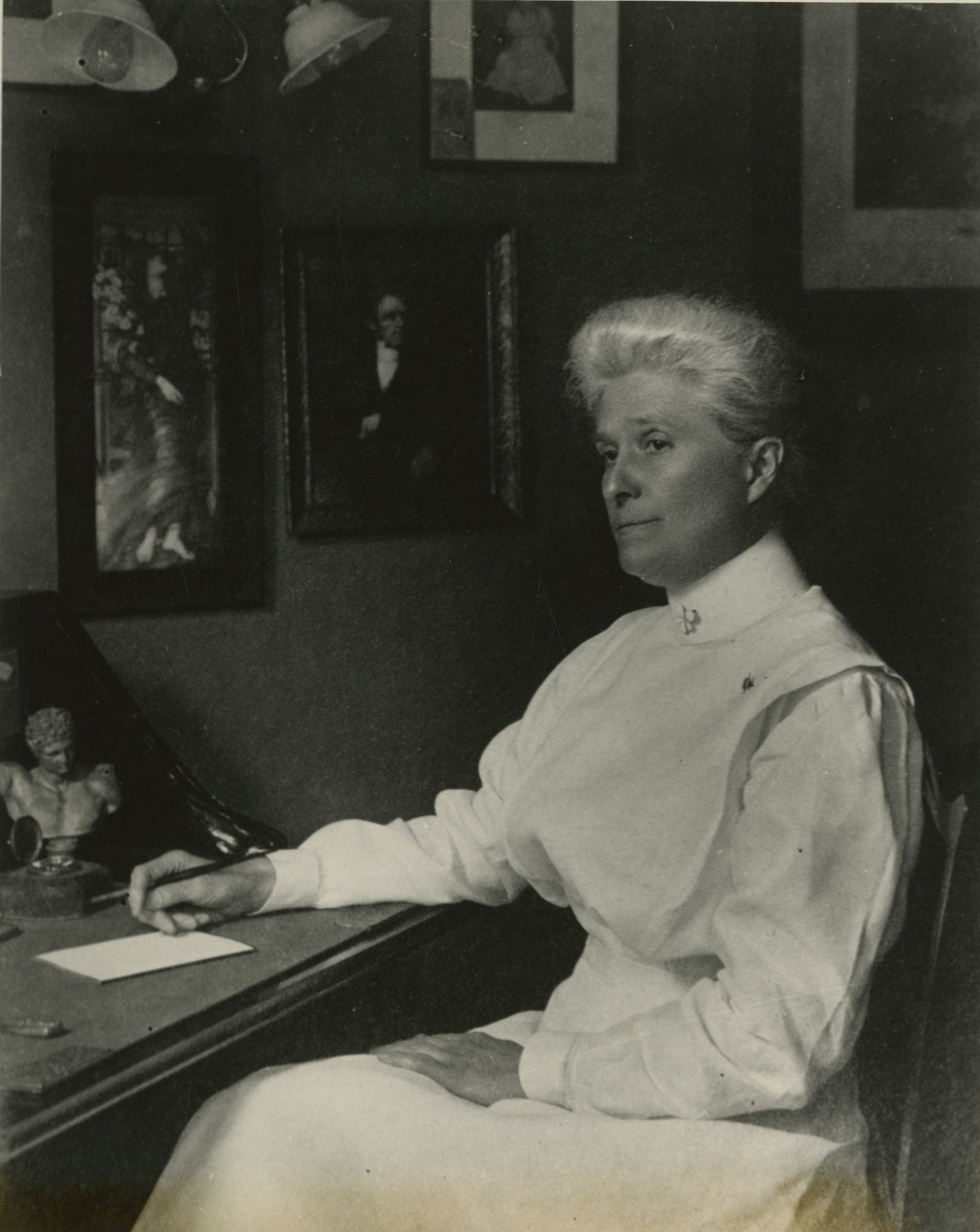

In February of 1929, a beautiful article published in The American Journal of Nursing paying respect to Anna C. Maxwell. Under her portrait that accompanied this article it states

Anna C. Maxwell who, in her long life of continuous service, has unswervingly upheld the most precious ideals of her art and science.

This statement encompasses everything that Anna stood for, as well as continued efforts to improve the care and the needs of her patients.

The following truly points out the knowledge and humility of Anna in her work. One day she passed Dr. William Darrach, who was the Dean of the Medical School of Columbia University, and greeted him -

"Good morning, Dr Darrach,I see that you have a case of tetanus on your ward.""Oh, no, Miss Maxwell, we have no tetanus."

As it is recorded, just days later it was confirmed that the ward did indeed have a tetanus. This record only continues to show proof that Anna was knowledgeable in the medical field and yet, she did not accuse or impart any judgment upon the physicians.

Another, Miss Adelaide M. Nutting of Teachers College, Columbia University, states:

"She was of the old school, firm in the traditions of her generation, guarding and cherishing them. The ideas prevalent when she began her work, and still existing in some measure, were that nursing was a calling which required of its votaries complete absorption in their task, and almost complete isolation from the normal human interests and social relationships of life. The ideal in fact of the religious orders" (Miller, 2017)

Anna Caroline Maxwell died on January 2, 1929. A service was held in her honor at The Chapel of The Union Theological Seminary and was attended by students, graduates, and many men and women representing medicine and nursing. The reverend Henry Sloan Coffin D.D spoke the following of her service and it truly pays homage to Anna and her service throughout her life. (James, James & Boyer, 1971)

"More especially we thank Thee for this Thy servant now at rest after long years of unremitting labor. For her upbringing in a godly home where early her spirit dedicated to a career of ministry; for her large native endowment in an acute and orderly mind, in personal magnetism, in power to kindle enthusiasm and gifts of leadership; for training in home and school continued by strict self-discipline in after years; for her devotion to her chosen calling and the lofty ideal she cherished of it; for the vision and courage and unflagging industry as teacher and executive early recognized; for the post of responsibility to which was chosen and were she proved herself worthy of the confidence reposed in her; for the many hundreds of nurses in whose education she had a share and who loved her in grateful and honored remembrance; for her patriotism and public spirit and readiness to answer the call of emergencies; for her practical outlook, free from sentimentality but aglow with passion for things true, just and helpful; for her capacity for friendship and for the loyalty she evoked from students and fellow-workers; for her hidden life of the soul with its reverence and faith and hope toward Thee, we offer our thanks. (p.187)

Anna’s procession included three groups of honorary pallbearers and her casket was carried through a lane lined with uniformed nurses. Additionally there were many in the medical field who worked alongside her that were present during her service and the procession. Not to mention that there were a select number who even made the journey from New York to Arlington Cemetery and were present when she was finally laid to rest. Among her fellow nurses and doctors that worked alongside her in the hospital scene, there were members of the American Red Cross who were present, as well as the Nurse Corps.

Though never officially enlisted in any branch of the military, The War Department approved for Maxwell to be laid to rest in Arlington Cemetery with military honors for her services in the Spanish-American War. She is one of the first women to be laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery with her headstone located in section 21, grave 16006.

References

- American Association for the History of Nursing (2018). Anna Caroline Maxwell 1851-1929 [website]. Retrieved from https://www.aahn.org/maxwell

- American Nurses Association. (2018, March 16). Hall of Fame Inductees [website]. Retrieved From www.nursingworld.org/ana/about-ana/history/hall-of-fame/1996-1998-inductees

- Anna Maxwell Headstone [Photograph], (2018, July 31). Anna Caroline Maxwell (1851-1929). Find a Grave. Retrieved from https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/18013863/anna-caroline-maxwell

- Hannik, E (2018). Anna Maxwell, the American Florence Nightingale [Working Nurse Website]. Retrieved from http://workingnurse.com/articles/Anna-Maxwell-the-American-Florence-Nightingale

- James, E. T., James, J.W., Boyer, P.S. (1971). Notable American Women, 1607-1950: A Biographical Dictionary, 2, 187.

- Lipincott, Williams & Wilkins (1921). Anna Caroline Maxwell, R.N., M.A. The American Journal of Nursing, 21(10), 688-697. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3407031

- Maxwell, A (1921). Struggles of the Pioneers. The American Journal of Nursing, 21(5), 321-329. https://www.jstor.org/stable/3407941?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

- Miller, K (2017, May 30). At War: A Heritage of Service. [Columbia University School of Nursing website] Retrieved from http://nursing.columbia.edu/war-heritage-service

- Patterson, M. R. (2007, August 9). Anna Caroline Maxwell: Nurse Corps, United States Army [Arlington National Cemetery website]. Retrieved from http://www.arlingtoncemetery.net/acmaxwell.htm

- Profiles in Nursing [Photograph], (2018, July 31). Anna Maxwell, the American Florence Nightingale. Working Nurse. Retrieved from http://workingnurse.com/articles/Anna-Maxwell-the-American-Florence-Nightingale