Hazel Johnson-Brown

Contributors

- Cambria White

- Kayla Schoebinger

- Katelin Graham

Editors/Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University

Early Life

Hazel Winifred Johnson, who later came to be known as Hazel Johnson-Brown, was born on October 10th, 1927, in Westchester, Pennsylvania to Clarence L. Johnson Sr. and Garnett Henley Johnson (ABNF Journal, 2011). Her father was born on June 27th, 1894, in Hockessin, Delaware (WikiTree, n.d.). Her mother was born on July 4th, 1903, in Nelson County Virginia (WikiTree, n.d.). Clarence was 33 and Garnett was 24 when Hazel came into the world. Johnson-Brown said this of her father: “Dad was a very deep man. He was quiet, thoughtful, very fiery temper, but he didn’t lose his temper that often. He was very thoughtful about his children… He thought about how we would have to face the world, and he taught us how to do that. He gave us the strength to know how to take care of ourselves in every kind of situation… He was also a strict disciplinarian. He believed that when one child did something wrong, all needed to know about it and share in the discipline. So he built him a bench, so when anybody did anything wrong, everybody had to sit on the bench, and pappy lectured” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). She stated that both of her parents placed a high value on their children’s education, even though her father only had education through the eighth grade.

She came from a family of nine, having four brothers and two sisters. Marie Johson was the oldest child, born 5 years before Hazel. Hazel was the second child in the Johnson household, followed by her brother John 2 years after she was born. Then came Clarence, Lloyd, Arthur, then Gloria, the youngest child, who was 11 years younger than Hazel. Johnson-Brown reports that her and her siblings were all close in their childhood years (Johnson-Brown, 2010). Hazel and her siblings loved to play outside. Whenever they were not learning or completing chores, they would race around the yard or ride bikes down the street. As the second oldest, Johnson-Brown was an exceptional example; her younger siblings looked up to her and valued her nurturing personality. Whenever Clarence was busy, Hazel would fill in her mother’s shoes and care for her younger siblings (Johnson-Brown, 2010). Johnson-Brown’s childhood household was continuously filled with noisy conversation. It was rare for the house to be silent unless it was deep in the middle of the night. The Johnson family was quite loved by their many friends. At an early age, Hazel was commonly immersed in conversations with many older adults. By the time she became an adult, she had already become an expert communicator.

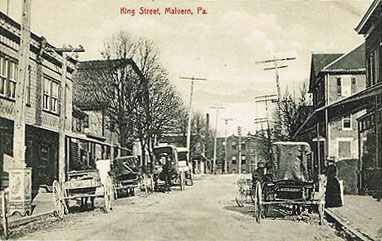

Soon after Hazel’s birth, her family moved 12 miles northeast to Malvern, Pennsylvania. Johnson-Brown stated: “My dad liked the country, so we kept moving until we finally found a place that he felt was large enough and he had land enough to do the kinds of things he wanted to do” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). Malvern was established in 1682 by William Penn, a Quaker (Malvern.org, n.d.), and consequently remained a hub for Quaker communities. Hazel noted that the Quaker people, because of their religious beliefs, did not make any distinction between white people and black people, and that their communities worked together quite well (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

At the time of Hazel’s birth, the town had a population of less than 1500 (Quann, 2011). The Johnson family had a farm on Valley Hill Road (Lukens, 2012) near a Quaker community where they raised livestock and grew their own crops (ABNF Journal 2011). They grew tomatoes and supplied them to the Campbell Soup Company (Lukens, 2012). Hazel’s devoted parents raised their children to place high value on discipline, work ethic, and education. They were expected to complete their home chores, help around the family farm, and work in the community (ABNF Journal, 2011). Johnson-Brown said: “I would help mom clean all the time. I would help her with the cooking. I wanted to learn how to make cakes, and so she taught me. I really wanted to always be building something and growing something” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). “My dad had seven kids - he didn’t have to hire anybody” (Eckhart, 2019). In addition to her household responsibilities and hobbies, Hazel, a diligent and obedient child, began her first job outside the home when she was 12 years old. She worked as a domestic worker in other individuals' homes. She was born during the great depression, but she says “We did quite well. We never knew anything about being hungry” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Around this time, Hazel decided that she wanted to become a nurse (Eckhart, 2019). Her younger sister, Gloria Smith, said that Hazel and the other Johnson children were often visited by Elizabeth Fritz, a family-friend and community health nurse they called “Miss Fritz”. The children loved it when Miss Fritz visited them and performed their check-ups. Miss Fritz was a role model, and in her later years, a mentor to young Hazel. Johnson-Brown also reports that she knew she wanted to become a nurse because she helped her mother take care of those who fell ill, and she really enjoyed that. She was also fascinated with anatomy and physiology.

Once inspired, Hazel worked hard to make her dream a reality (Lukens, 2017). She was an incredibly focused and driven child. Of this she said, “I was always a planner, I was always one that wanted to get things taken care of and in order” (Lukens, 2017). These characteristics that manifested in childhood stuck with Hazel throughout her life. As a child, she attended East Whiteland Elementary School in East Whiteland Township, PA, three miles from her home. Then Tredyffrin-Easttown Junior and Senior High School (which is known as Conestoga High School today), located in Berwyn, PA, four miles away from her home.

Social Issues

Johnson-Brown was born into the era of segregation, (Eckhart, 2019). The Johnson family was the only black family in their neighborhood, and some of the few black children in their schools. Of this she said: “We integrated the schools, especially in grammar school we were the integrators” (Johnson-Brown). When she was asked what that was like she responded with: “We were a confident crew. We didn’t think about it as being integrating, we were just going to school like we were supposed to! Now we knew we were the only ones of that color, but that was okay, it didn’t bother us” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

In her adult years, Hazel was able to laugh about the way she was treated as a child due to her race. She said “It probably was [a tough environment for a child to grow up in], but my father taught us that we were worth being who we were. And you had to be who you knew you were, not what someone else thought you were” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Hazel said that she was fortunate to live out in the country instead of in the city, because the town was segregated, but things were more relaxed out in the rural areas (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

In her lifetime, Johnson-Brown went head-to-head with many racist attitudes. She recounted the following incident in an interview:

“Well, I knew there was a racial difference because we got called names very frequently by our colleagues who were young kids, you know. I knew about that. But the first time I understood it in terms of being used to prevent me from doing something was two times. The first time was when I went to Philadelphia to take the exam for nursing. And Mom said, `I'm hungry. Let's stop over here at this hot dog stand and get a hot dog.' And I said, `OK.'”

So, we walked up to the stand, and then here comes some white people. And the woman walked over and waited on the white people, walked right by us. The next time she came by and she walked by us again. So finally, she got back to us. So, I went and made the order and so forth. And I guess it was my father in me because I had thought about it and I was going to get her. I waited until she got the order and got it, brought up to me, and I said to her, `Now you eat it,' and told Mom, `Let's go.'” (Cox, n.d.).

Hazel knew she was born different from the other children, and although Pennsylvania was not a strictly racially segregated state at the time, it was still exceedingly difficult for a woman of color to attain a career in nursing (Eckhart, 2019). Hazel told this story about applying to nursing school:

“The more important time was when Miss Fritz who was the--she was the visiting nurse--county nurse for the community. And she was very good to us. She was very good to everyone. She was a white woman, but she was very good. She took care of us, made sure we went to the dentist at least once a year and that we got any kind of ailment taken care of. And she liked the idea that I was interested in nursing. She said, `Well, we can do this. You've got to take the exam and then we'll go over to West Chester District County Hospital,' which was in West Chester, `and they have a student program. They'll get you in there.' So she took me.

Well, the director of nursing met us and said to her and myself, 'We've never had a black person in our program, and we never will.' I thought Ms. Fritz was going to have apoplexy but we got out of there and she said, `I know what we're going to do. Harlem Hospital School of Nursing has an excellent program. I'm going to get you in there.'” (Cox, n.d.).

Hazel was asked, “How did you feel when you heard that woman say that to you?” (Cox, n.d). She responded, “It really hurt. It made me feel very--you know, like somehow I was less, but it also made me really angry. And I'm like my father upside-down. I said, `OK, there will be a day and I'll get you.' But that's a terrible way to--but I held that thing in my heart until I got her. I did and it was five years later, but I made sure I got her.”

The interviewer responded with, “How'd you get her?” Hazel responded with, “I went over there and she had to hire me then because they had passed a rule of law that said they did. I went to work for her. I worked for one week and I quit. I already had another job. I was already working in Philadelphia at the Veterans Hospital. I did that to fix her” (Cox, n.d.).

Of this experience she said “Now I’ve learned to channel that anger a little differently. I don’t let myself get uptight about it now. When people got a problem, that’s their problem… You can be sure of one thing, I’m not going anywhere, I’m staying. And you’re going to have to come by me eventually, so it might be wise to get over that” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Social issues did not stop Hazel from succeeding in her career. She was very forward thinking and believed that if a person was qualified, they should be able to do the job. Her competence led her to achieve many important things in her lifetime.

Education

Johnson-Brown did not let negativity grasp a hold of her life; instead, she worked harder to overcome these obstacles. Although distraught and heartbroken, she persevered and applied to multiple other nursing schools. Her hard work paid off. In 1947, Johnson-Brown moved to New York City and enrolled in the Harlem Hospital School of Nursing. She lived with her aunt. Of Harlem, Johnson-Brown said, “All the places were so close together, you felt like you were being squeezed!” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). She said that during her time in nursing school that the city was a very safe place, and that she would be out walking around at night without any discomfort. She reports that it only became a dangerous place when drugs and alcohol started flooding the streets in later years (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Harlem Hospital opened in 1887. It began in a Victorian mansion where East 120th Street and the East River met in New York City. In 1907, the hospital relocated to the east side of Lennox Avenue. It started small but expanded to meet the needs of a continually growing community. In 1915, the hospital constructed a residence for the nursing staff. The hospital was founded with the goal to give African Americans who were aspiring to be nurses and physicians equal career opportunities. Harlem Hospital is home to the first Black physician in any city hospital in America. In 1958, two black cardiothoracic surgeons on the hospital’s staff saved Martin Luther King Jr.’s life following a stab wound to the chest. They used a procedure that Dr. Maynard developed himself (Columbia University Medical Center, n.d.). Harlem Hospital gave many black medical professionals the chance to innovate and practice medicine, proving to the people of New York that they had much to offer.

Lincoln Hospital School of Nursing in North Carolina was the first school to accept African American women, and Harlem Hospital School of Nursing was the second. The nursing school was opened in January of 1923 in response to the other city hospital’s refusal to accept black students (Columbia University Medical Center, n.d.). “Harlem has been called many things; as it has evolved in the City of New York, reference to that northern portion of Manhattan Island has always evoked strong emotions. Harlem has been referred to as the ‘Negro Metropolis,’ a ‘Black Mecca,’ the fountainhead of mass movement, and sometimes as the most famous ethnic city in the world” (Bennett, 1984). This demonstrates the prejudice against the people of Harlem city, a predominantly black community. However, due to the demographics, Harlem was an appropriate location to place a nursing school to attract black students. The Harlem School of Nursing was a segregated school sponsored by the local municipal government. The curriculum was modeled after what was being taught at Bellevue Training School, a white nursing school in New York that was also sponsored by the local government (Bennett, 1984). The first graduating class of Harlem Hospital School of Nursing consisted of 20 African American students. The program lasted two and a half years. The nursing school was closed in June of 1978.

After three years, Johnson-Brown graduated from Harlem Hospital School of Nursing in 1950. Hazel said that the training at Harlem Hospital was “second to none” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). She said, “You see everything, you work with everything, and you have excellent professors” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

She told a story about one professor that made an impact on her nursing education: “There was one woman, Mrs. Adams. She was a tall black woman, brilliant, brilliant. But she could see through walls, I can tell you, she could see through walls. You’d be having a problem, and ten seconds later you’d look up and she’d be in the doorway coming in… She’d stay there and help you out. She wouldn’t do it, but she would guide through what you needed to do… She really cared about us...She really was trying to help us to know, when we have problems, how to solve them” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

After returning from Camp Zama, Japan in 1958 (mentioned in more detail under military career), Hazel went into the inactive army reserves and went back to school to get her baccalaureate degree in nursing from Villanova University (Johnson-Brown, 2010). She participated in the Army Nurse Corps’ Registered Nurse student program, which gave financial assistance to nurses who were going back to school in pursuit of a bachelor’s degree (Foundation for Women Warriors, 2020). Villanova is a well-known university in Pennsylvania. Villanova ranks 53rd in the National Universities. Hazel said: “I didn’t have any problems there at Villanova. In fact, the faculty there were incredibly good, and so were the students. We all worked together. We weren’t concentrating on race; we were concentrating on getting out of that course and getting a B at least!” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

After Hazel’s time as an operating room nurse at Walter Reed Army Medical Center (see “Military Career”) she decided she wanted to teach nursing students the art of working in the O.R. In response to this desire, she obtained her master's degree of Nursing Education from Columbia University’s Teachers’ College in 1963 (AWFDN, 2021). Following this, she returned to Letterman General Hospital to teach.

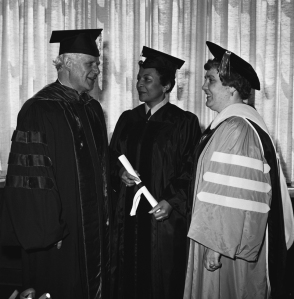

Hazel was selected by the U.S. army to receive her Doctorate of Nursing. She was thrilled to be following her passion for teaching. She attended Catholic University of America in Washington D.C. and got her Ph.D. in education administration. She began this program in 1973, and upon completion, she was made the director and assistant dean of Walter Reed Army Institute of Nursing in 1976. She was the first African American woman and the first chief to earn a doctorate degree in the Department of Defense (Sarnecky, 2021).

Hazel was also awarded honorary degrees from Morgan State University, and the University of Maryland (Fenison, 2009).

Early Nursing Career

Hazel committed her early life to her education, she studied diligently and found herself in the top of her class. While in school, Hazel discovered her love for the emergency ward. After graduating nursing school, she began her career in the emergency department at Harlem Hospital. She talked about how she often cared for many people who would come in for alcohol intoxication or drug addiction, and she would help them detox (Johnson-Brown, 2010). Of this she stated: “That is what I expected nursing to be, taking care of people. You take care of people at their worst, not their best'' (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

In 1953, after working at Harlem Hospital, Hazel went to work at the Veterans Hospital in Philadelphia. However, she wanted to also work part time at the hospital in West Chester to make some extra money to get her bachelor's degree, but also to send a message. The hiring manager of West Chester District County Hospital was the same woman who declined Hazel a spot in their nursing program. Hazel said: “I went over to that place to get a job and that woman told me ‘We’ve never had any black nurses working on staff here, but we are beginning to make that change now. You can possibly work here. So I went to work there” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

She said: “She mentioned to me that she didn’t expect me to wear my pin which you get when you're graduated to show you're a registered nurse. I looked at her and said ‘I’m wearing my pin, I earned it. It’s mine to wear” (Johnson-Brown 2010).

Hazel said with a laugh: “Well, it was like they had put someone in from outer space, because it was like everyone in the hospital visited that ward that [the day I started]” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

An interviewer asked her “What kind of impression did you get of what the black people felt seeing you there?”, to which Hazel replied “They were proud, they were happy...because they knew that was going to break that color line and get things started. And it did” (Johnson-Brown).

Hazel ended this story by saying: “I only worked there two or three weeks, I was making a point. I was there to make a point, and it was that I was going to be there” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Hazel worked on the cardiovascular wing of the Philadelphia Veteran’s Hospital. This hospital was one of the only hospitals at the time that allowed Hazel to work. Wages for American Africans were much lower than Caucasians, but despite this set back, Johnson-Brown became head nurse within three months, which was unheard of at the time. Hazel said: “There was a nurse who was working with me, a young white woman, who was very upset that I got the job. She had been there longer than I. Part of that was because of the way I worked. Well I came out of Harlem, I had been taught well. I knew how to organize my work, I knew how to work with the men and women who worked as aides… Even when I wasn’t head nurse I worked as though I was” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Military Career

In an interview about her life, Hazel said: “I had been [at the VA hospital] about two years, and one of the supervisors said to me… ‘You would be good in the army!’ I said ‘Really? Why?’, and she said, ‘You know how to organize things and get them done!’. I said 'Well, don't we do that in the civilian world?’ and she said ‘Yeah, but not as well as you do. You’ve got a military attitude!” (Johson-Brown, 2010).

Hazel was intrigued by the variety of opportunities the army had in store and thought “it would be an opportunity that would allow her to explore the world and hone her nursing skills” (Rock, 2021), so in 1955 she enlisted. One of the appeals of the army was that they were working on the ethylene-oxide sterilization aeration project. This was a study about using gas to sterilize surgical tools. She was excited to be on the cutting edge of medicine (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

The army had been desegregated in response to President Truman’s executive order in 1948. (Ourdocuments.gov, n.d.). Hazel said she was not met with any opposition regarding her race when she enlisted. She credits this to Maggie Bailey, the first African American colonel in the U.S. army, saying that “she paved the way, and those before her, who maybe didn’t get promoted but were willing to stand up and be counted. You’re always standing on so many shoulders” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Hazel completed her basic training in San Antonio Texas. She began her first two-year assignment in 1955, on the female medical-surgical ward at Walter Reed Army Medical Center in Washington, D.C. She was a staff nurse in the U.S. Army Nurse Corp and a Second Lieutenant in the army (Lukens, 2012). The Walter Reed Army Medical Center was founded in 1909, and was named after Major Walter Reed, who was the lead researcher who discovered that yellow fever was transmitted via mosquitoes. In 2011, it was merged with the National Naval Medical Center located in Bethesda, MA in response to an act written by the U.S. Congress. Before them, this hospital served over 750,000 veterans and their family members annually, tens of thousands of soldiers during WWI, WWII, and the Korean and Vietnam wars.

Before her two-year assignment was complete, she was transferred to the obstetrical unit at the 8169th Hospital in Camp Zama, Japan (Foundation for Women Warriors, 2020). The ancestral unit of Camp Sama was first started in California in December of 1942. It then moved to New Guinea, Philippines, and finally to Japan in 1944. In September of 1945, after the surrender of the Japanese Military Hospital, the United States took possession and established the first U.S. Army Hospital in Japan. While at this hospital, Hazel “soon discovered that obstetrics was not her “bailiwick,” and asked to never again work in that specialty, [however] she deliberately finished that assignment with her typical sense of commitment” (Sarnecky, 2021).

From 1957 to 1959, Hazel returned to Pennsylvania to pursue her bachelor’s degree (more information under the “Nursing Education” section). In 1959, Johnson returned to the Army and was assigned to Madigan General Hospital in Washington. This hospital was named after Colonel Patrick S. Madigan, assistant to the Surgeon General of the U.S. from 1940 to 1943. He was known as the Father of Army Neuropsychiatry. It was previously known as Fort Lewis General Hospital, but in 1944 it was re-dedicated to honor its namesake, who died on May 8th, 1944. /

In 1960, Hazel became a first lieutenant and found her passion in nursing, the operating room. She was formally trained as an operating room nurse at Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco. Following this training course, Hazel returned to the Walter Reed Army Medical Center to work in the operating room. She loved her time in the operating room. She said: “I suddenly discovered I could see the stomach, I could see the heart, I could see the liver. Hey, this is where I wanna work! Because now I know what it looks like. It’s not a picture in a book. It’s real. So I asked the operating room supervisor, ‘Whenever you have a case and you need someone to scrub, can I come and scrub?’’ (Johnson-Brown). Her obituary stated that she “rose in the ranks as she impressed her superiors with her skill in the operating room” (Legacy, 2011).

Following Hazel’s Master’s program (more information in the “Nursing Education Section”, Hazel got her first job teaching aspiring nurses. From 1963 to 1966, she taught operating room students at Letterman Army Hospital in San Francisco, and many of her students would later be deployed to Vietnam. By 1964, Hazel was promoted to Captain in the U.S. army (U.S. Army Medical Dept., n.d.).

In 1966, Hazel Johnson Brown was given a special assignment. She would travel to Texas to be the operating room supervisor for the Mobile Unit Self-Contained Transportable (MUST) hospital, or as she called it, the “inflatable hospital” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). These were hospitals that could quickly be assembled and worked out of when needed. The MUST was used across Vietnam as the guerrilla warfare caused the battlefield to be unpredictable. The MUST’s would include areas for radiology, dental, pharmacy, and more. However, she was unable to go to Vietnam to test these portable units out, as she fell ill with a lung infection. “I got a lung abscess. Working in that dusty, dirty warehouse I guess that’s what did it. Nevertheless, I was diagnosed early on and got that taken care of” (Johnson-Brown).

Hazel spent a month recovering, and then was sent to Valley Forge in Pennsylvania. She worked at the Medical Research and Development Command as the first nurse. “They were having a problem with the central service... that was the supply area where you sterilize all the equipment...So I went over there and I helped get that organized” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). “She was most recognized as the director of the Field Sterilization Equipment Development Project” (Foundation for Women Warriors).

In an interview in 2010, Hazel was asked the following question about this position: “As you got promoted and moved more and more into these other areas like Research and Development, weren’t you being moved more and more away from your first love, which is hands on patient care?” to which Hazel responded “No. You see, hands on is fine, but there’s so much else that has to be done that directly relates to patient care. And you need to be involved in that process, because then it makes what's going on at the bedside easier. And the best way is to be at the starting point” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). She worked on this project for six years, after which she went back to school to get her Ph.D. (See the “Nursing Education” section). By 1972, Hazel was promoted to Colonel in the U.S. army (U.S. Army Medical Dept., n.d.).

Upon completion of her doctoral studies in 1976, Hazel was appointed Director and Assistant Dean of the Walter Reed Army Institute for Nursing in Washington D.C. This school was an extension of the University of Maryland’s nursing school. It opened in 1964, after signing a contract with the U.S. Army to provide baccalaureate nursing education. It was a unique military nursing school, as it attracted many black nursing students, as well as male students. 1,100 students graduated from this school before it closed in 1978 (University of Maryland, 2018). Lieutenant Colonel Johnson fought this closure with her usual vigor, while also defending her dissertation (Sarnecky, 2021).

Following the school’s closure, Lieutenant Colonel Johnson traveled to Seoul, Korea to work at the 121st Evacuation Hospital. She was the senior ranking US military nurse in South Korea and the Chief Consultant for Nursing Matters to the Senior Medical Officer, 8th Army Command” (Legacy, 2011). The 121st Evacuation hospital “was originally activated in 1944 as the 121st Evacuation Hospital, Semi-mobile. It participated in the European Theater during World War II and in the Korean War. It has served continuously in Korea as a field unit since Sept. 25, 1950, and as a fixed medical treatment facility, Seoul Military Hospital, since 1959. In 1971, Seoul Military Hospital merged with the 121st Evacuation Hospital to become the U.S. Army Hospital” (My Base Guide, 2016). Today it is known as Brian Allgood Army Community Hospital (My Base Guide, 2016).

In 1979, Lieutenant Colonel Johnson was promoted to the position of Chief, Army Nurse Corps and to the rank of Brigadier General (Legacy, 2011). She was the first black chief of the Army Corps, and the first black female Brigadier General (U.S. Army, n.d.). “A military ceremony was held in her honor at the Pentagon, where U.S. Army Surgeon General Julius Richmond pinned on her the brigadier general star” (Fenison, 2009). A Brigadier General is a one-star general officer that is above a colonel, but below a major general. This office commands over 4,000 troops. The insignia to distinguish a Brigadier General is a single silver star on their shoulder or their collar. The first female Brigadier General was Anna Mae Hays, just nine years prior (Army Heritage Center Foundation, 2021).

Regarding this promotion, Hazel told this tender story about her and her mother: “My mother told me... ‘Hazel, you’re going to get something very special in your life, and you’ll do well with it… She died two days later, and the next day they announced it. And I said, ‘Mom knew it’” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

.jpg)

In an interview in 2010, Hazel was asked: “When you got to be the first black woman general, how did it feel?” To which she responded: “It was really very, very exciting, I was really tickled, and I was sad too, because I felt there were some people before me who should have had that opportunity because they certainly were excellent people” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). She was also asked: “Does it bother you to even have people say ‘she was the first black woman general’ as opposed to ‘she was a general and she did a great job’ and the other adjectives apply?” Hazel responded by saying: “No I think it’s important. I’m proud to be the first black woman general… and I’m proud for my people to be proud” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Brigadier General Johnson led over 7,000 nurses in the Army National Guard and Army Reserve. General Johnson set policy and oversaw operations in eight Army medical centers, 56 community hospitals, and 143 free-standing clinics in the United States, Japan, Korea, Germany, and Panama (Rock, 2021). She helped Reserve Officer Training Corps (ROTC) nursing students by opening scholarship programs for them and establishing a clinical summer camp for the cadets. She published the Army Nurse Corps’ first Standard of Practice document. She put together the Phyllis Verhonick Nursing Research Symposium. She was involved in planning the Strategic Planning Conference, which was designed to bring representatives from the rank and file of the army nurses together to plan for the future of the corps. She advocated for the further education of army nurses, proposing that Army Nurse Corps specialty courses be replaced by graduate education at universities for more in-depth training. She advocated for more leadership positions for nurses in the reserves and national guard (Sarnecky, 2021).

Post-Military Career

When asked in an interview if it was hard to retire, Hazel said: “No, because I prepared myself to do another job, and that was teach” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). She also stated that she had no regrets, due to her having a wonderful career.

Following her retirement in 1983, she accepted a job as an associate professor at the School of Nursing at Georgetown University in Washington D.C. She had planned to start working in the fall, but when approached by the American Nurses Association months earlier to help organize their office, she gave up her free time to help. She started working at the office as an administrative consultant and eventually was promoted to Director of Governmental Affairs. She would end up working there for three years. She did all of this while also teaching at Georgetown in Washington D.C. (Sarnecky, 2021). The School of Nursing and Health Studies at Georgetown was founded in 1903 with the vision of providing degrees that aim “to promote health equity and improve population health locally, nationally, and globally” (Georgetown University, n.d.).

In 1989, Hazel took on full professorship at George Mason University in Virginia. Here, she played a significant role in a passion project designed to educate and involve nurses in health policy and policy design. As such, the Center for Health policy was born at George Mason (U.S. Army, n.d.), and Dr. Johnson-Brown was the director (George Mason University, 2016). In 1996, she was promoted to Professor Emeritus of the College of Nursing and Health Science. She worked here until her retirement in 1997 and remained an active participant on the nursing advisory board until she passed away. While working here, she balanced her academic duties with volunteering to work in the surgical suite at Fort Belvoir Army Hospital in Virginia during Operation Desert Storm (Sarnecky, 2021).

A webpage in honor and remembrance of Dr. Hazel Johnson-Brown posted by George Mason states that: “Alumni and faculty most often recall her commitment to mentoring students and her forward-thinking attitude” (George Mason University, 2016). She is remembered as saying “"Positive progress towards excellence, that's what we want. If you stand still and settle for the status quo, that's exactly what you will have” (George Mason University, 2016).

Dr. Charlene Y. Douglas, a current professor at George Mason University and previous White House Fellow from 1991-1992 said this of Hazel: “General Johnson-Brown taught me the importance of procedure. There is a way to do everything, but most importantly, there is a way to do everything well. Her lessons guided my tenure as the first nurse to be Chair of the George Mason University Faculty Senate. Those lessons in leadership remain important in my life and career” (George Mason University, 2016).

Dr. Germaine Louis, dean of the College of Health and Human Services said: “[Hazel] has a special place in her heart for students defying the odds to attend nursing school and often mentored them” (The Afro, 2017).

Lieutenant Governor Bethany Hall-Long, a mentee of Johnson-Brown while getting her Ph.D. at George Mason said she learned two important lessons from Johnson-Brown: “always fight for a seat at the table or you’ll wind up on the menu, and don’t apologize for things you have nothing to be sorry about” (The Afro, 2017). She also said: “She was truly a trailblazer, the first African-American female brigadier general but she didn’t let the titles get to her. She was straight up with you and loving and understanding.”

The University has set up a scholarship in Hazel’s honor, “to recognize [her] inspirational guidance and mentorship for hundreds of nurses” (George Mason University, 2016). The scholarship comes from the General Hazel Johnson-Brown Endowed Scholarship Fund and Endowed Nursing Chair fund, and is awarded to low-income, high achieving nursing students. The Endowed Nursing Chair Fund was set up to “secure innovative, forward-thinking faculty members to educate tomorrow’s nurses leaders” (George Mason University, 2016). On November 13th, 2017, the university launched a yearlong campaign to raise $500,000 for these initiatives.

Johnson-Brown enjoyed teaching; it was one of her favorite phases of life. Teaching allowed her to not only share her nursing experiences, but also grow and learn herself. The medical field is constantly changing, and by teaching, Hazel’s skills continually improved. She taught nursing courses as well as health administration courses. Johnson-Brown was a kind and loving professor, but she also made her students work hard. Her courses were not easy A’s. This was one of the many reasons as to why she was respected. Students took her courses knowing they would have to work hard, but in return, receive a quality education. Hazel took pride in her students, and she looked forward to the days where she could send them off to begin their journey as nurses (Sarnacky, 2021). She was constantly striving to be a role model. She said, “You have to model yourself so that someone looking at you can say ‘I can do that too’” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). Her teaching philosophy was always to narrow the focus to the patient, and ask “what am I doing to help my patient?” (Johnson-Brown, 2010). In an interview near the end of her life, she said: “I see that people I’ve worked with exceed what I’ve accomplished, which is what I would expect, simply, because that is what’s supposed to happen. I’m the ground floor now, and they are stepping on that, and that is what’s supposed to be” (Johnson-Brown, 2010).

Awards

On top of her promotions, Hazel was recognized with many awards during her military service. In the early 1960’s, Hazel received the Army Distinguished Service Medal. This medal was “authorized by Congress in 1942 to award members of the Armed Forces for their meritorious conduct and outstanding service” (MOA, 2019). This medal is awarded by the Army, Air Force, Navy, and Homeland Security. She also received the Legion of Merit award. This award “was authorized by Congress in 1942 to award members of the Armed Forces for exceptionally meritorious conduct and outstanding service” and is awarded to persons in key positions of power and responsibility (Medals of America, 2019). She also received the Meritorious Service Medal, which award was created in 1969 to be awarded to “member[s] of the military of the Armed Forces of the United States for having set him or herself apart from his/her comrades by outstanding non-combat meritorious achievement or service to the United States” (Powers, 2019). She also was awarded the Army Commendation Medal, which is given to those in the Armed Forces that exemplify themselves in an act of heroism or perform an extraordinary achievement.

In 1964, Captain Hazel Johnson was given the Evangeline G. Bovard Award, which honors the Letterman Army Medical Center’s outstanding nurse of the year. This award was established by Colonel Robert Skelton in memory of his wife who was an army nurse at Letterman, and later passed away there.

Along with many medals, Johnson-Brown was named the Army Nurse of the Year, multiple times, one being in 1972. This title is handed to an active-duty Nurse Corps officer by the Surgeon general. It is paired with the Dr. Anita Newcomb McGee Award, which was created by the Daughters of the American Revolution in memory of the organizer of the Army Nurse Corps (U.S. Army Medical Dept, n.d.).

In 1984, Hazel received the Candance Award. This is an award given by the National Coalition of 100 Black Women to “black role models of uncommon distinction who have set a standard of excellence for young people of all races” (Candace, 2003).

She was well known for her skills and excellence. She is remembered as saying this after she received her promotion to brigadier general: “I hope the criterion for selection didn’t include race but competence” (AAREG, 2020). Her work ethic and passion for nursing and educating touched all those around her.

Personal Life

Throughout Hazel’s life and career, she was a positive role model. She was a high caliber nurse and passed her knowledge on to hundreds of students at Letterman, Walter Reed, Georgetown, and George Mason University. She carried the principles she learned in her childhood of high moral character and hard work with her in all her doings. Her hard upbringing led to her ability to work harder than the average person to attain success. Johnson-Brown had a soft side to her as well; she knew what it was like to be treated with disrespect, so she made it her life goal to treat people of all races, creeds, and genders with compassion and fairness. Her difficult past most definitely shaped her future for the better.

When commenting on why she did not marry in her younger years, she said: “Well, when I went into nursing you were not allowed to be married. But I also found that it is very difficult for a woman to find a man who can cope with the problems inherent in a busy and time-consuming schedule. From my point of view, I had to decide what was more important, marriage or my career” (Ebony, 77). However, in the last few years of her military career, she met David Brown. They got married in 1981, where she took on the last name of Brown. Their marriage was brief and did not result in any children. Johnson-Brown did not remarry, but she did keep the Brown last name. Hazel was already retired when the two divorced.

Following this, she moved to Wilmington, Delaware to live with her sister, Gloria Smith.

Hazel Johnson-Brown died on August 5th, 2011, at the age of 83 years old (Langer, 2011). She had a short battle with Alzheimer's, and her life ended en route to a hospital in Wilmington (Sarnecky, 2021).

.jpg)

Hazel Johnson-Brown was deeply devoted to her field of work and her country. Chester County Hospital officials noted that, “General Hazel Johnson-Brown demonstrated individual perseverance to rise above the many barriers facing African American women and men in the last century. We all have much to learn from her life. It is also important to be reminded of how far our society has advanced in the past 70 years, and the work that still lies before us” (Lukens, 2012). Her life was remembered at her home with a small ceremony, and a tribute was hosted by the DeBaptiste Funeral Home in West Chester, along with a memorial service at her church, St. Clare, in Clifton, Virginia. After these services, her military funeral was held in the Arlington National Cemetery.

This military cemetery is specifically for individuals who dedicated their lives for the benefit of the United States of America. The Arlington Cemetery is in Arlington, Virginia. To be buried in this cemetery, the individual needs to have been a veteran that was never dishonorably discharged during their service, a veteran that died in active duty, active duty for training, or inactive duty for training, or lastly a spouse or minor of a veteran. The location of her plot can be found in section 60, site 9836. “General Hazel Johnson-Brown will forever be remembered in the annals of American military history” (Luken’s, 2012).

She was survived by the countless nursing students whose lives she touched. She was an educator at her very core, and inspired people to be the best they could be. This quote from M. Millie that was found in a eulogy written for Johnson-Brown perfectly sums up her personal mantra; one she passed on too many others: “We must never lose our drive. We must be persistent in following our dreams. Nothing can stop you. We must let the power of our passion propel us into becoming skilled in our field. We are all great, and we can all become greater. The question is are you willing to do what needs to be done to achieve the greatness that is destined for you?” Her legacy calls all nurses to rise to the occasion and be the best they can be.

Johnson-Brown’s legacy still lives today. She will forever be known as the first black women general of the United States military. She is an inspiration to the nursing field due to her perseverance and dedication. She found her passion in nursing, and although it was not easy, she worked hard to overcome the many obstacles that stood in her way. Johnson-Brown’s charismatic personality touched thousands of lives. She cared about her work, but even more importantly, she cared about everyone she interacted with. Loved and respected, Hazel Johnson-Brown will forever have an impact on the nursing field.

References

- The Afro-American Newspaper Company. (2017, November 16). Black Female General’s Legacy Grows at George Mason University. https://afro.com/black-female-generals -legacy-grows-george-mason-university/.

- Army Heritage Center Foundation. (2020, September 11). From Patriot To Pioneer: Brigadier General Anna Mae Hays. https://www.armyheritage.org/soldier -stories/from-patriot-to-pioneer-brigadier-general-anna-mae-hays/.

- Bennett, M. A. (1984). A history of the Harlem Hospital School of nursing: Its emergence and development in a changing urban community, 1923-1973 (dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, Ann Arbor, MI.

- Children's National Hospital. (2021). History of Walter Reed - research and Innovation campus: Children's National. https://childrensnational.org/about-us/our-health- system/childrens-national-research-and-innovation-campus/history-of-walter-reed.

- City of Malvern . (n.d.). History. Malvern Borough. http://www.malvern.org/general-info/ about-malvern/early-history/.

- Columbia University. (2018, April 26). A History of Anticipating—and Shaping—the Future. Teachers College - Columbia University. https://www.tc.columbia. edu/about/history/. Used to obtain an early image of Columbia University Teachers College.

- Davidson, A. T. (1957). A History of Harlem Hospital. Journal of the National Medical Association, 56(5), 373–392.

- City of Malvern . (n.d.). History. Malvern Borough. http://www.malvern.org/ general-info/about-malvern/early-history/. Used to obtain a picture of a Harlem Hospital School of Nursing.

- Ebony, August 1977, p. 76; February 1980, p.44.

- Eckhart, T. J. (2019, October 10). She Earned Three Firsts in the Army. Monroe County Now. https://www.monroecountynow.org/blog/2019/10/10/she-earned-three-firsts-in-the-army.

- Encyclopedia.com. (2019). Johnson, Hazel 1927-. https://www.encyclopedia.com/ education/news-wires-white-papers-and-books/johnson-hazel-1927.

- Fenison, J. (2021, July 1). Hazel W. Johnson . https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/johnson-hazel-w-1927/.

- George Mason University. (2016). About General Hazel Johnson-Brown. George Mason University Alumni. https://advancement.gmu.edu/s/1564/GID2/16/interior -1col.aspx?sid=1564&gid=2&sitebuilder=1&pgid=3113.

- George Mason University. (2016). About general Hazel Johnson-Brown. George Mason University Alumni. https://advancement.gmu.edu/s/1564/GID2/16/interior-1col.aspx?sid=1564&gid=2&sitebuilder=1&pgid=3113.

- Georgetown University. (2021, July 6). School of Nursing and Health Studies. https://nhs.georgetown.edu/.

- Harlem Hospital Center. (n.d.). Our History. Our History | Residency Programs. https://www.cumc.columbia.edu/harlem-hospital/about/history.

- “Hazel Johnson-Brown, General, U.S. Army.” Foundation for Women Warriors, 23 Mar. 2020, foundationforwomenwarriors.org/hazel-johnson-brown-general-u-s-army/.

- “Hazel W. Johnson-Brown Biography.” Drexel University Online, 8 July 2020, www.online.drexel.edu/news/digital-dragon.aspx/year-of-the-nurse-johnson-brown.

- In Memory Of.. (2011). ABNF Journal, 22(4), 83.

- The History Channel. (n.d.). Executive order 9981: Desegregation of the armed forces (1948). Ourdocuments.gov. https://www.ourdocuments.gov/doc.php?flash=false& amp;doc=84.

- Jean C. Whelan, P. D. (2015, February 26). Does American Nursing Have A Diversity Problem? Echoes & Evidence: Nursing History and Health Policy Blog. https://historian.nursing.upenn.edu/2015/02/26/diversity_nursing/.

- Langer, E. (2011, August 18). Hazel Johnson-Brown, Army nurse who was the first black female general, dies at 83. The Washington Post: Democracy Dies in Darkness. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/obituaries/hazel-johnson-brown-pioneering-black-army-nurse-dies-at-83/2011/08/18/gIQA0E2MOJ_story.html.

- Legacy.com, & Legacy. (2011, August 10). Hazel Johnson-Brown Obituary (2011) - Wilmington, DE - The News Journal. Legacy.com. https://www.legacy.com/obituaries/delawareonline/obituary.aspx?n=hazel-w-johnson-brown&pid=153020951.

- Lukens, R. (2017). History's People: Hazel Johnson-Brown, First Female Black General. http://www.chestercohistorical.org/historys-people-hazel-johnson-brown-first-female-black-general.

- MacBeath, E. (2020, December 16). Clarence L Johnson. WikiTree. https://www.wikitree. com/wiki/Johnson-101409.

- MacBeath, E. (2020, December 16). Garnett (Henley) Johnson . WikiTree. https://www.wikitree.com/wiki/Henley-1632.

- Madigan's Namesake. Madigan Army Medical Center . (n.d.). https://madigan.tricare.mil/ About-Us.

- Military History Facts. Military History Facts (3) - The National Board of the ROCKS, Inc. (n.d.). https://www.rocksinc.org/content.aspx?page_id=22&club_id=459944& module_id=55918

- MyBaseGuide. (2021). Chapter 10: Korea. https://mybaseguide.com/installation/tripler- army-community-hospital/community/chapter-10-korea/.

- Pierce, L. (2018). Exploring The Experiences Of African American Nurses: An Emancipatory Inquiry (dissertation).

- Powers, R. (2019, November 20). Meritorious Service Medal. https://www.thebalance careers.com/meritorious-service-medal-3344967.

- Quann, C. (1961, October). The History of Malvern. Tredyffrin Easttown Historical Society History Quarterly Digital Archives. https://tehistory.org/hqda/html/v11/v11n4p 088.html.

- Robertson, S., Fisher, D., & Wilson, J. R. (2019, March 4). Harlem's Hospitals. Digital Harlem Blog. https://drstephenrobertson.com/digitalharlemblog/ maps/harlems-hospitals/. Used to obtain an early image of Harlem Hospital.

- Sarnecky, M. T. (2021). Brig. Gen. Hazel Johnson Brown. https://www.awfdn.org/trailblazers/brig-gen-hazel-johnson-brown/.

- Sarnecky, M. T. (2021). Brigadier General Hazel W. Johnson16th Chief, Army Nurse Corps. Superintendents & Chiefs of the ANC . https://e-anca.org/History/Superintendents -Chiefs-of-the-ANC/Hazel-W-Johnson.

- SPAS Research. (2021). Malvern, Pennsylvania. Spouts, Springs, Fountains, and Holy Wells of the Malvern Hills. http://www.malvernwaters.com/ nationalparks.asp?search=yes&p=7&id=76. Used to obtain a picture of Malvern, PA.

- Thomas, C. (2013, April 17). A look back at nurses in 1950. Heart Sisters. https://myheartsisters.org/2013/05/07/a-nurses-life-in-1950/.

- TONY COX. (n.d.). Profile: Hazel Johnson Brown, the first African-American female general in the US Army. Tavis Smiley (NPR).

- University of Maryland: School of Nursing. (2020). Walter Reed Army Institute of nursing. https://www.nursing.umaryland.edu/museum/virtual-tour/military-history/wrain/.

- U.S. Army. (n.d.). Brig. Gen. Hazel Johnson Brown. African Americans in the U.S. Army: Profiles of Bravery. https://www.army.mil/africanamericans/profiles/johnson.html#:~:text=Brig.,African%20American%20female%20brigadier%20general.

- U.S. Army Medical Department. (2009). Highlights in the History of the Army Nurse Corps: Appendices. Office of Medical History. https://history.amedd.army.mil/ANC Website/append.html.

- U.S. Department of the Interior National Parks Service. (2018, April 13). National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form. https://gis.penndot.gov/CRGISAttachments/Survey/2018M001042A_01H.pdf. Used to obtain an early image of the Philadelphia VA hospital.

- Weebly. (n.d.). Eulogy. Hazel Winifred Johnson-Brown. https://741799043286545307 .weebly.com/eulogy.html.

- WITF, Inc. (2019). A panorama of Fedigan's Folly, Villanova University, c1902. Explore PA History. http://explorepahistory.com/displayimage.php?imgId =1-2-18CC. Used to obtain a picture of the early Villanova University.

- Wordpress. (2014, February 11). Hazel Johnson-Brown: Trailblazing nurse. Black Women Who Know Their Worth. https://blackwomenwhoknowtheirworth .wordpress.com/2014/02/11/hazel-johnson-brown-trailblazing-nurse/. Used to obtain images of Hazel receiving her doctorate, promotion to general, and general images of her.