Mary Seacole

Contributors

- Savannah Clawson

- Nicole Croft

- Torina Dredge

Reviewers

- Sean N. Bennett, RN, MSN - Associate Professor - Utah Valley University - Orem, Utah

The Life of Mary Seacole

About Mary Seacole

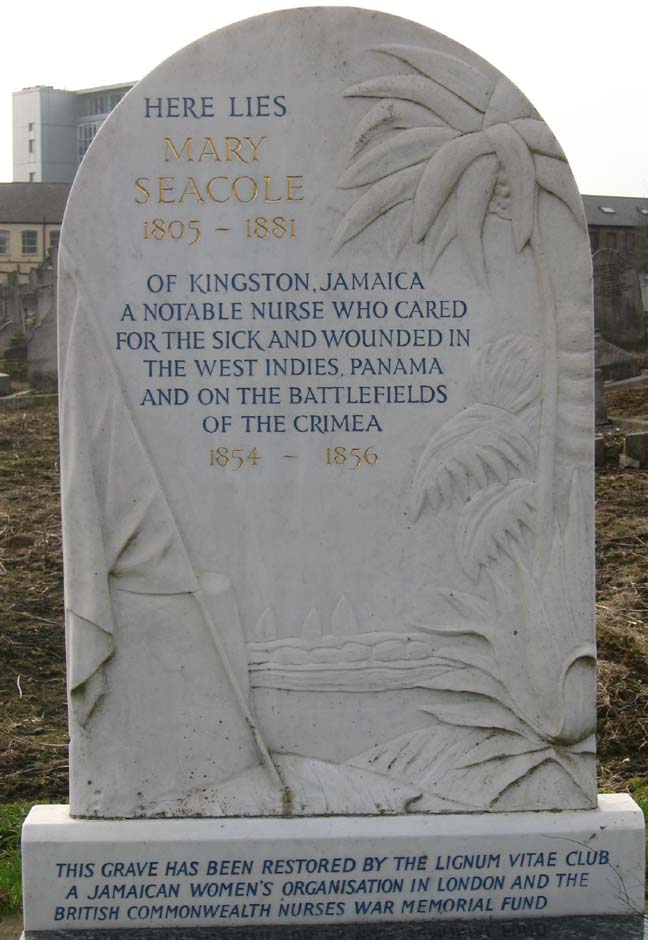

Mary Seacole was born in 1805 and died in 1881, was one of our pioneering nurses of the 18th century and played a large part in the Crimean War. She was a woman of mixed race and due to being mixed race, has to work tirelessly throughout her life to overcome her double prejudice (bbc, 2014). Mary was known to be a compassionate nurse, skilled doctress, and educated entrepreneur who greatly impacted the course of nursing. Her contributions are celebrated and her legacy continues to live on today.

Early Childhood 1805-1815

Mary Jane Seacole (Grant) was born November 23, 1805 in the land Kingston, St. Andrew Parish, Jamaica to (Father) Lt. James Grant and (Mother) whose name is unknown. Her Father Lieutenant General James Grant was born in the year 1770 in Scotland and was an officer in the British Army. Mary’s mother was born in the mid-1770s in Jamaica and was a previously freed Creole who was practicing as a skilled doctress in traditional medicine.

Mary Seacole was born of mixed race with her father being a white Scottish and her mother being a black Jamaican. This was not socially acceptable at the time and it caused Mary to fight a double prejudice throughout her life. Mary’s mother belonged to a small number of freed blacks and creoles in Jamaica. Her father, being a part of the British military, was stationed in Jamaica to help secure the island against the Spanish. During his stay in Jamaica, he met Mary’s mother.

Mary was proud of her mixed Scottish and Jamaican race and often referred to herself as a creole, which was a racially neutral term given to children born of mixed race between a soldier and native woman. In her autobiography, Mary wrote “I am a Creole, and have good Scots blood coursing through my veins. I have a few shades of deeper brown upon my skin which shows me related and I am proud of the relationship to those poor mortals whom you once held enslaved, and whose bodies America still owns” (Seacole). Mary Seacole being the daughter of a Scottish general and a free black doctress would have been ranked socially high in Jamaica but unfortunately had many more restricted rights anywhere else.

Mary had a younger sister, Elizabeth (Eliza) Louisa Smith (Grant) born 1815 and a younger brother named Edward Grant born shortly after. Mary was the oldest of the three by ten years and helped to care for them while they were young. While in Jamaica, Mary spent many of her childhood years in the household of an educated elderly Scottish woman. The “kind patroness”, as she referred to her, treated Mary with kindness and respect. She treated her as one of the family and while in her home, gave Mary a good education.

Mary’s fascination with medicine came from the time she was just a child. Her mother used traditional African herbal remedies and owned a boarding house for wounded and sick soldiers. From a young age, Mary acquired these same nursing skills from her mother and would practice on her dolls which quickly progressed to her pets until she was working alongside her mother in treating patients .

Mary’s Education

Mary Seacole was born in a time where women and people of color had little rights and although Mary had both prejudice throughout her life, she was given the upper hand when it came to her education. Mary’s father was a white male which allowed Mary the opportunity to receive an education equal to one of the upper classes. Although Mary was part Scottish, she was not granted the same rights an all-white person normally would have. This was because Jamaica was part of the British Empire in the 1800’s. Some of these restricted rights included voting, being in public office or even getting a job (Caffery, 2016). However, according to some sources, Mary was loyal to the British Empire and shared many English values (Paquet, 2017). It is unknown if Mary attended public school but we do know that she was very educated and taught by the people around her. Mary spent most of her time being taught and looked after by an educated elderly Scottish woman whom Mary viewed as more of a grandmother or aunt rather than a nanny. In Mary’s autobiography, she refers to the woman as her “kind patroness”. A patron is a person of wealth who assists poorer people. While in her care, her patroness taught Mary about the fine arts, literature, English and other languages, mathematics, geography, and much more. (Advameg 2018)

Though she spent most of her time being cared for by her patroness, Mary’s mother and father were not negligent in Mary’s education. Mary’s mother was one of the very few freed black creoles and with her freedom, she practiced as a doctress and business owner in Jamaica. Mary’s mother was very knowledgeable herself and from the time Mary was just a child, her mother taught everything she knew about their traditional African and Caribbean herbal remedies and how to treat and care for the sick and injured. Mary loved the practice of medicine and would practice what her mother taught her on her dolls which quickly progressed to her pets until she was skilled enough at the age of twelve to be working alongside her mother in treating actual patients. Mary said, “I have always noticed what actors children are… whatever disease was most prevalent in Kingston, be sure my poor doll soon contracted it… before long it was very natural that I should seek to extend my practice, and so I found other patients in the cats and dogs around me” (Seacole 1857).

Mary’s mother also taught her the business side of things as she owned and ran “Blundell Hall”, which was a boarding house and was considered one of the best hotels in all of Kingston. Mary took those business skills and put them to work. At one point in life, Mary owned stocks and was invested in the gold rush which allowed her to pay for her own travels to Central America, Britain, Panama, England, Cuba, Haiti, Bahamas, and Crimea (CMSimple, 2016). This was her major occupation and with each travel destination Mary would learn a lot about caring for the sick. She would collect details of how the sick were being treated and what local plants and herbs were being used. Mary used the knowledge she learned in both traditional medicine and European medicine. Mary also had contact with many military physicians throughout her life. She watched what they did to treat their patients and applied much of that knowledge into her own nursing practice. Ultimately, Mary had learned and applied the skill of being a compassionate nurturer throughout her life. She stated in her autobiography “I do not pray to God that I may never see its likes again, for I wish to be useful all my life” (Seacole 1857)

Teenage years 1816-1822

Jamaica was established as a British colony in 1655 and slaves were shipped in during 1509 (BBC, 2012). Because of this, Mary only knew her homeland to be a British colony and did not know what true equality felt like. Nevertheless, Mary truly cared for the British Empire; she often traveled there as a teen and later in her life she traveled to Crimea to support and care for the British troops; Mary even considered herself a British citizen (National Geographic Education Staff, 2013). During Mary’s teenage years, Britain celebrated triumph as they and their allies defeated the French in the War of Liberation (1814) (infoplease, 2017). And in other worldly news, Guatemala, Panama, and Santo Domingo proclaimed independence from Spain in 1821 (infoplease, 2017). Panama was a place that Mary moved to later in her life so this independence is noteworthy. Not only did Mary travel later in her life but was an active traveler in her teenage years as well.

In the 19th century women did not have a lot of rights and were not known to travel but unlike other women, one of Mary Seacole’s favorite things to do was just that. Mary traveled to England twice when she was a teenager and spent a total of three years there (National Geographic). Mary once wrote in her journal, “As I grew into womanhood, I began to indulge that longing which will never leave me while I have health and vigor... I was never weary of tracing upon an old map the route to England; and never followed with my gaze the stately ships homeward bound without longing to be in them, and see the blue hills of Jamaica fade into the distance,” (Oxford Press, 1990). While in London, she continued to study medicine and add her newly acquired knowledge to the things her own mother had taught her. After her three years in England, Mary traveled to the Bahamas, Haiti, and Cuba. On these trips, she bought goods to sell back home in Kingston, Jamaica (National Geographic Education Staff, 2013).

Young Adulthood 1823-1840

In 1836, Mary married Edwin Horatio Seacole. He was a former guest at her mother’s boarding house (History in an Hour, 2012). Edwin was described as a White, English, merchant in Jamaica. It was believed that Edwin was either an illegitimate offspring of Lord Nelson and his mistress, Lady Hamilton, or he was Nelson’s godson. Nevertheless, he was adopted into the Seacole family. The time period showed that mixed race relationships were common, but mixed race marriages were rare. As a newly married couple, they moved to Black River and opened a provisions store. Edwin had very poor health and passed away 8 years later. In her autobiography, Mary described her marriage to becoming a widow in only 9 lines. Her husband’s death started a series of bad events that happened to Mary at this time. Her mother passed away shortly after her husband did, and in 1843 her Kingston home along with her boarding house was destroyed in a fire that almost killed her. She grieved for a period of time, “turned a bold front to fortune”, and then assumed management of her mother’s hotel (No author, 2007). She attributed her fast recovery to her “hot Creole blood” and blunting the “sharp edge of her grief (No author, 2007). She declined many offers for marriage because she was so dedicated to her work at this time. She became well known and respected especially from the European military visitors in Jamaica.

In 1850, Mary’s half-brother moved to Panama. There he followed family tradition and opened a hotel to accommodate the many travelers between the east and west coast of the United States. The 1849 California Gold rush caused an increase of travelers in the area (No author, 2007). Shortly after Mary traveled to Panama to visit her brother. At this time it was struck with Cholera. Mary treated the first victim helping them survive. This helped boost her reputation and brought in additional patients as the disease spread. The rich paid for her service and she treated the poor for free.

Cholera

In 1850, a bacterial disease known as “cholera” spread across the island of Jamaica and killed more than 31,000 people (Seaton, 2016). Mary gained firsthand knowledge of this disease by working alongside many doctors. To find the best way to care for her patients containing cholera, she spent many hours studying what antics worked and didn’t in the treatment of this disease. While visiting her brother in Panama, sanitary conditions were unfavorable. These conditions along with the hot humid weather became a “breeding ground” for tropical diseases (Seaton, 2016). Cholera spread vigorously over the towns yet there failed to be little medical help from any doctors on the island. Mary had the knowledge and persisted to assist the infected. At first the people were reluctant for Mary to help because not only was she a woman but she was of mixed racial backgrounds which was not accepted, but due to increased need for medical care they were forced to allow her aid. She worked long nights and days, and was credited for saving many lives (Seaton, 2016). Mary moved to Cuba and was so good at caring for those with cholera that she became known as the “yellow woman from Jamaica with the cholera medicine” (Seaton, 2016).

Middle Age 1841-1853

Mary Seacole’s luck with money went through various stages. She claimed, “Sometimes I was rich one day, and poor the next,” (Seacole 1857). She believed that money was not the key to happiness and that if she had made a big deal about wealth, she would have been heartbroken over her failures. A major failure and disappointment occurred in 1843 when her home in Jamaica was burnt down. She almost lost her life trying to save her home. It devastated more than just Seacole’s home, it hurt a big part of Kingston Jamaica as well.

Mary worked hard and rebuilt her home and began to work as a “nurse and doctress” for invalid officers and their families. At times, a military surgeon would stay in her hotel and she would ask them to teach her techniques. The surgeons often were happy to teach her because she was so passionate of learning.

In 1850, Seacole decided she would help her brother run his hotel in Cruses Panama. She left her home to her cousin in Jamaica and set off straight away. After a long and arduous journey, Seacole reached her brother in Cruces. “...it was destined that I should not be long in Cruces before my medical skill and knowledge were put to the test. Before the passengers for Panama had been many days gone, it was found that they had left one of their number behind them, and that one – the cholera,” (Seacole 1857). It was clear to Mary Seacole that the people did not know that cholera was contagious. Many of the people of Cruses blamed the outbreak on American travelers from New Orleans. Mary Seacole helped all she could during this outbreak in Cruces.

Mary Seacole came back to Kingston, Jamaica. There had been a serious epidemic sweeping across the nation and for eight months in 1853 where she helped treat those with yellow fever. Seacole was getting restless and was ready to travel again. She made arrangements to go the Isthmus of Panama where she had a hotel. “Before I left Jamaica for Navy Bay (and then to Panama)... war had been declared against Russia, and we were all anxiously expecting news of a descent upon the Crimea. Now, no sooner had I heard of war somewhere than I longed to witness it; and when I was told that many of the regiments I had known so well in Jamaica had left England for the scene of action, the desire to join them became stronger than ever,” (Seacole 1857). Mary longed to see war, and to use her knowledge and skill to help in Crimea. However, Mary soon realized, “when I came to talk over the project with my friends, the best scheme I could devise seemed so wild and improbable, that I was fain to resign my hopes for a time, and so started for Navy Bay (then on to Panama),” (Seacole 1857).

The Crimea War

As Mary lived in Panama, she could not shake the feeling of wanting to be in Crimea. “So I made long and unwearied application at the War Office, in blissful ignorance of the labor and time I was throwing away,” (Seacole 1857). Her first application was denied, she tried to get to Crimea through the Crimean Fund, but that plan failed also. The next morning, Mary had made a new plan, “If in no other way, then would I upon my own responsibility and at my own cost,” (Seacole, 1857).

In the fall of 1854, a year after the war between Russia and the United Kingdom began, Mary Seacole traveled to England to be a volunteer nurse and care for the injured British soldiers and offered her services to the War Office in addition to the wife of the Secretary of state, Elizabeth Herbert (Gabriel, 2004). She did not get an interview from either places even though she had many references from former military officers in Jamaica. She applied to Florence Nightingale's Organization, and got turned down again even though there was a great need of nurses at the time (Seaton, 2016). Mary thought that the rejection was due to her race. Mary did not give up so easily. Still wanting to go to Crimea, she applied to the managers of the Crimea fund to help with travel expenses. She was rejected once again. Mary said, “Was it possible that American prejudices against color had some root here?” (Gabriel, 2004). She was distraught, but composed herself and decided to travel at her own expense.

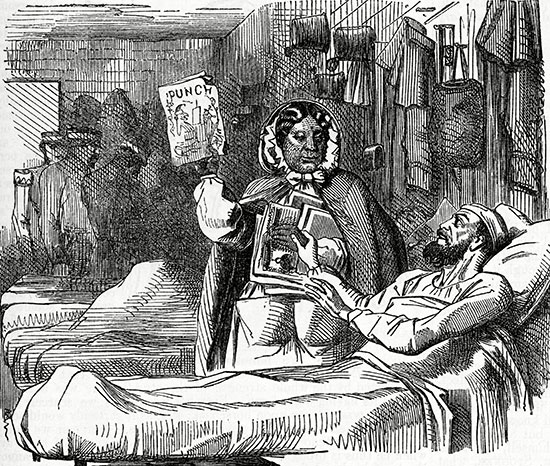

When Seacole got to Crimea, she was reunited with some of those same military surgeons. She thanked them again for the knowledge they shared, “...which helped me to be useful to my kind in many lands,” (Seacole 1857). Mary Seacole took on many patients and often worked tirelessly in Crimea. Mary said, “I tell you, reader, I have seen many a bold fellow's eyes moisten at such a season, when a woman's voice and a woman's care have brought to their minds recollections of those happy English homes which some of them never saw again; but many did, who will remember their woman-comrade upon the bleak and barren heights before Sebastopol,” (Seacole 1857). She was, if anything, a comfort to the soldiers who did not have much to be hopeful for.

After two long years of service in Crimea, Mary desired to come back to Jamaica saying, “Before the New Year was far advanced we all began to think of going home, making sure that peace would soon be concluded. And never did more welcome message come anywhere than that which brought us intelligence of the armistice, and the firing, which had grown more and more slack lately, ceased altogether,” (Seacole 1857). Mary did all she could and more to help the British soldiers in Crimea; she was ready to come home.

Mary’s Other Occupations

Mary Seacole was a nurse by heart, but a business woman by trade. Mary was a compassionate person and had a love for nursing and giving care to others, yet worked hard to make a substantial living for herself throughout her life. Mary being a caregiver by heart, mainly focused her businesses around the provision of food and goods for those in need. Mary inherited the Blundell Hall boarding house in Kingston Jamaica after her mother’s death along with property in Panama. Mary continued to run the boarding house with her husband for many years, but after the death of her husband, Mary joined her brother in panama in 1850. Together they established a hotel that served as both a boarding house and store much like the one in Kingston.

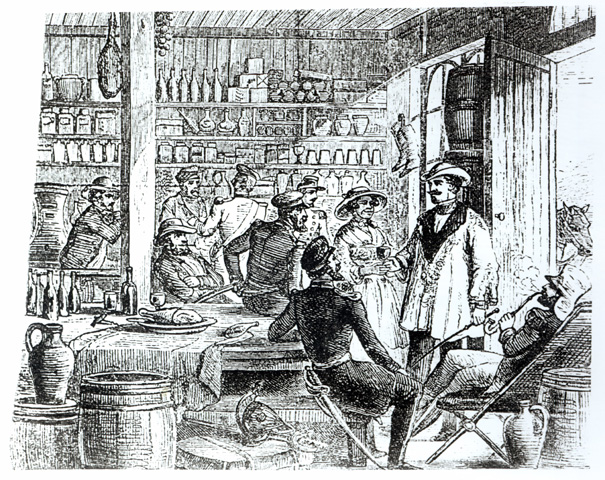

The store in Panama was to serve the men who were setting out for the California Gold rush. In their store they sold, clothing, meats, vegetables, and eggs along with many other preserved foods. Mary stated “My house was full for weeks of tailors, making up rough coats, trousers, etc., and seamstresses making shirts… my kitchen was filled with busy people manufacturing preserves, guava jelly and other delicacies” (CMSimple 2016).

Mary’s ventures in Panama were extremely profitable. There in Panama she started a partnership with Thomas Day, who was a distant connection of her late husband.

Mary also at one point owned stocks and was invested in the gold rush herself. Both of these helped finance her many travels to Central America, Britain, Panama, England, Cuba, Haiti, Bahamas, and Crimea. Through her many travels, Mary was always looking to collect native products of each land that she could sale in her stores such as sea Shells from the Bahamas or spices from Cuba. With the investments Mary had inquired in the gold mining business, she was able to provide her own way to the Crimea peninsula in 1853 when the Crimea war began. In 1855 Mary set up a store and a boarding house in Balaclava (city on the Crimean peninsula) which she called “The British Hotel” located in the heart of Crimea. The bottom floor was like a restaurant and the top floor a hospital. She was generous in serving others, but also wanted to be paid for her services. She had lost most of her investments during her travel and found herself lacking the necessities to run a successful business. The hotel was built from salvaged packing cases, iron sheets, salvaged driftwood, glass, and doors. Her British hotel was failing and in an attempt to continue success, Mary stopped providing rooms and beds and concentrated on serving only food and beverages. At one point she started offering outside catering in attempts to save her business (CMSimple 2016).

During the day she worked in her boarding house, and at night she volunteered with Florence Nightingale. She started a medical practice working with the enlisted men who did not want to go to the hospital. In camp, she was soon known as the doctress, nurse and even mother. She became well known when she was seen treating the wounded on the battlefields, even though the battle was still taking place. She was recognizable as the lady in the yellow dress, blue bonnet with red ribbons and medical bag (Seaton, 2016). She would load her bag of supplies on one mule and her medical equipment on another mule.

When Sebastopol fell in 1855, Mary was privileged enough to be the first woman to enter Sebastopol and pass out refreshments and tend to the injured. She became known as the “black Nightingale”. She was always praised very highly from the soldiers, but she was never officially recognized or rewarded from the military.

In 1856 the Crimea war had ended and Mary found herself broke with no more soldiers to serve so she slowly made her way back to England venturing many lands along the way. After one year of travels Mary arrived in England in 1857 being in poor health and destitute, yet she immediately set up a small shop in Aldershot Hampshire. This shop was short lived as it too was very unsuccessful. Mary at this point was declared bankrupt but not for long. A fund was set up in her name shortly after where many prominent people who had heard and were impressed by her help, devotion, and service in the war donated large funds. Mary used the donated funds to return home to Kingston Jamaica where she was assumed to have retired (CMSimple 2016). Mary was an extremely dedicated business woman and caregiver who always used the success of her businesses to travel to other lands and offer help to people in need. Mary said “rather ten times die in the surf heralding the way to a new world than stand idly on the shore” (Seacole 1857).

End of Life

Mary died in Paddington, London on May 14, 1881 at the age of 76. Her death certificate listed apoplexy as the cause of her death. The Times and Manchester Guardian published obituaries with her recognition even though she was out of the public eye for 25 years (Seaton, 2016). After that, Mary Seacole seemed to fade from memory. Her work in Crimea was overshadowed by Florence Nightingale’s for many years (No Author, 2007).

In 1954, a century since the Crimean War, it was attempted to restore her place in history. The Jamaican General Trained Nurses’ Association decided to name their Kingston headquarters the Mary Seacole House when it was built (Seaton, 2016). A residence hall at the University of the West Indies and a ward in the Kingston Public Hospital was named after her. She was not recognized in Britain until 1973.

On November 20, 1973, a special ceremony of consecration was held at Mary Seacole’s grave. A woman by the name of Elsie Gordon, a former editor of the Nursing Mirror, found a piece of paper in a copy of Mary Seacole’s autobiography that she bought at a London bookstore. This specific piece of paper helped Gordon locate Seacole’s grave in St Mary’s Roman Catholic Cemetery (Seaton, 2016). Before this finding, no one knew where Seacole was buried. Her crumbling headstone was restored and a ceremony was conducted. A memorial service was held on May 14, 1981 to mark a century since her death. It was so popular that it became an annual event.

Mary’s Legacy

Mary Seacole made an enormous impact on many people’s lives. Whether she was in Kingston, England, Panama or Crimea, Mary was caring for everyone she could. Because of her amazing work, many people try to pay tribute to her and celebrate her accomplishments. There was a Gala held in her honor, “between 27 and 30th July 1857 at the Royal Surrey Gardens, on the banks of the River Thames in London; over 80,000 people attended. Mary was swindled by the owners and receive very little of the funds, however, she never lost her dignity and that year published her celebrated autobiography ‘Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands’,” (RAFFA). When Mary died in London on May 14, 1881, she was laid to rest in St Mary’s Catholic cemetery. There, she received “’English, French, Russian and Turkish decorations,’” (RAFFA) undoubtedly because she was admired by so many.

Other tributes to Mary included: being voted as the greatest ever black Briton, a Google Doodle was created October 14, 2016 to try to pay tribute to her, a memorial statue has been erected at St Thomas Hospital which is said to be the first ever statue in the UK that honors an African American woman (Cockburn 2016), NHS Employers turn to the example of Mary Seacole as they award the “Mary Seacole Award” once a year to, “…provide an opportunity for individuals to be recognized for their outstanding work in the black and minority ethnic (BME) communities,” (nhsemployers 2018), the Mary Seacole Memorial Association holds an annual wreath laying ceremony and lecture on the second Saturday of May in her honor. Awards, statues, monuments, mosaics, paintings, biographies, operas, and much more have been created in honor of this strong, determined woman

Mary Seacole’s legacy lives on through these celebrations; she is renowned for being a “woman of determination, discipline, character, courage and caring,” (RAFFA).

References

- This is an item in a list

- Advameg. Inc. (2018). Mary Seacole Biography. Retrieved from http://www.notablebiographies.com/supp.Supplement-Mi-So/Seacole-Mary.html#ixzz5H UcA7C5d

- BBC (2014). History of Mary Seacole 1805-18821. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/historic_figures/seacole_mary.shtml.

- Caffrey, C. (2016). Mary Seacole. Salem Press Biographical Encyclopedia.

- CMSimple. (2016).MarySeacoleInformation. Retrieved from http://www.maryseacole.info/?Introduction:The_Life_of_Mary_Seacole

- Gabriel, D. (2004). Great Jamaicans: Mary seacole 1805-188. Retrieved from http://jamaicans.com/maryseac/

- Hartston, W. (2014, March 28). Top 10 facts about the Crimean War. Retrieved from https://www.express.co.uk/life-style/top10facts/467286/Top-10-facts-about-the-Crimean-War http://nursinglink.monster.com/nurse-supervisor-jobs/articles/9655-historic-nursing-uniforms-the -good-the-bad-and-the-ugly?print=true

- History in an Hour. (May 14, 2012). Mary seacole- a summary. Retrieved from http://www.historyinanhour.com/2012/05/14/mary-seacole-summary/.

- Jamaica timeline. (2012, August 20). Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/americas/country_profiles/1191049.stm

- Mary Seacole. (2018, August 03). Retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mary_Seacole

- Mary Seacole Biography. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://www.notablebiographies.com/supp/Supplement-Mi-So/Seacole-Mary.html

- Mary Seacole Facts for Kids. (2018, April 26). Retrieved from http://www.natgeokids.com/nz/discover/history/general-history/mary-seacole/.

- No Author. (n.d.). History. Retrieved from http://rootsroutes.com/history/

- National Geographic Education Staff. (2012, October 15). Mary Seacole. Retrieved from http://www.nationalgeographic.org/news/mary-seacole/.

- No Author. (2007). Mary seacole. Retrieved from https://www.cs.mcgill.ca/~rwest/wikispeedia/wpcd/wp/m/Mary_Seacole.htm

- Paquet, S. P. (2017). The enigma of arrival: The wonderful adventures of Mrs. Seacole in many Lands. African American Review, 50(4), 864.

- Seacole. Mary. J. (1857). Wonderful Adventures of Mrs. Seacole in Many Lands. Retrieved from http://digital.library.upenn.edu/women/seacole/adventures/adventures.html

- Seaton, H. J. (2016, September 8). Another Florence nightingale? The rediscovery of Mary Seacole. Retrieved from http://www.victorianweb.org/history/crimea/seacole.html.

- Unknown. (2018). Mary Seacole. Retrieved from https://www.geni.com/people/free-Jamaican-Creole-woman/6000000012999823850

- Walters, G. (2012, December 30). The black Florence Nightingale and the making of a PC myth: One historian explains how Mary Seacole's story never stood up. Retrieved from http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2255095/The-black-Florence-Nightingale-making-PC-myth-One-historian-explains-Mary-Seacoles-story-stood-up.html

- Welsh, K. (Ed.). (2018, May 24). Mary Seacole. Retrieved from https://www.geni.com/people/Mary-Seacole/6000000012999561591